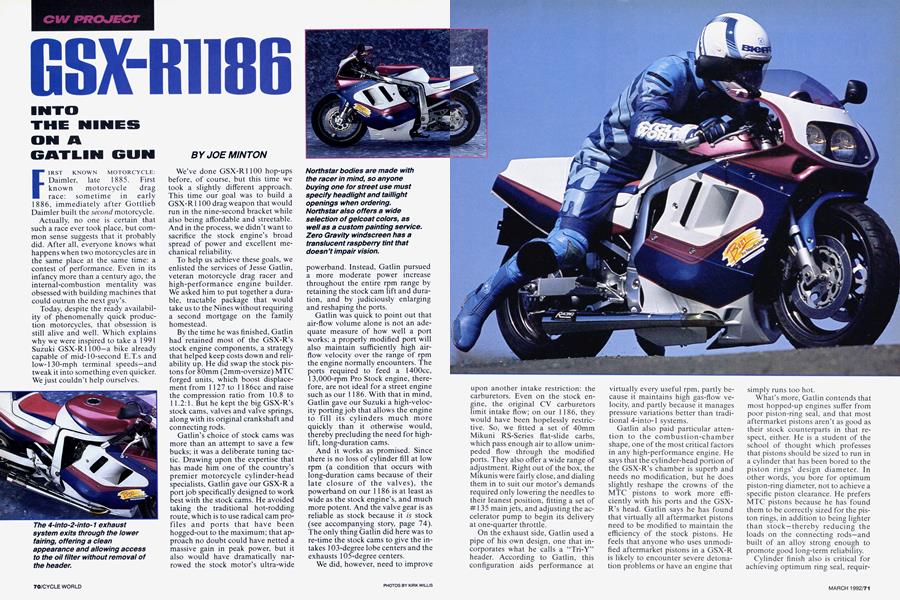

GSX-R1186

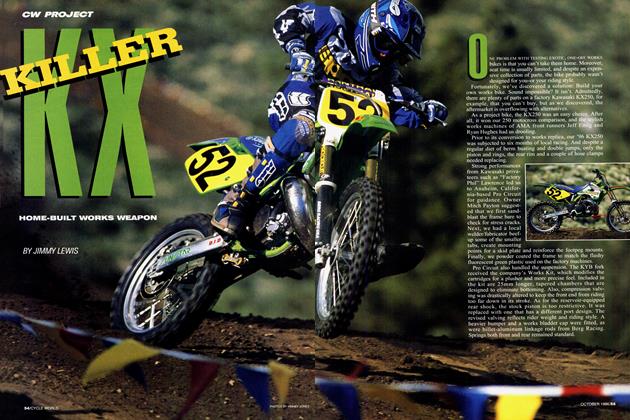

CW PROJECT

INTO THE NINES ON A GATLIN GUN

JOE MINTON

FIRST KNOWN MOTORCYCLE: Daimler, late 1885. First known motorcycle drag race: sometime in early 1886, immediately after Gottlieb Daimler built the second motorcycle.

Actually, no one is certain that such a race ever took place, but common sense suggests that it probably did. After all, everyone knows what happens when two motorcycles are in the same place at the same time: a contest of performance. Even in its infancy more than a century ago, the internal-combustion mentality was obsessed with building machines that could outrun the next guy’s.

Today, despite the ready availability of phenomenally quick production motorcycles, that obsession is still alive and well. Which explains why we were inspired to take a 1991 Suzuki GSX-R 1100—a bike already capable of mid-10-second E.T.s and low-130-mph terminal speeds—and tweak it into something even quicker. We just couldn’t help ourselves.

We’ve done GSX-R 1100 hop-ups before, of course, but this time we took a slightly different approach. This time our goal was to build a GSX-R 1100 drag weapon that would run in the nine-second bracket while also being affordable and streetable. And in the process, we didn’t want to sacrifice the stock engine’s broad spread of power and excellent mechanical reliability.

To help us achieve these goals, we enlisted the services of Jesse Gatlin, veteran motorcycle drag racer and high-performance engine builder. We asked him to put together a durable, tractable package that would take us to the Nines without requiring a second mortgage on the family homestead.

By the time he was finished, Gatlin had retained most of the GSX-R’s stock engine components, a strategy that helped keep costs down and reliability up. He did swap the stock pistons for 80mm (2mm-oversize) MTC forged units, which boost displacement from 1127 to l I86cc and raise the compression ratio from 10.8 to 11.2: l. But he kept the big GSX-R’s stock cams, valves and valve springs, along with its original crankshaft and connecting rods.

Gatlin’s choice of stock cams was more than an attempt to save a few bucks; it was a deliberate tuning tactic. Drawing upon the expertise that has made him one of the country’s premier motorcycle cylinder-head specialists, Gatlin gave our GSX-R a port job specifically designed to work best with the stock cams. He avoided taking the traditional hot-rodding route, which is to use radical cam profiles and ports that have been hogged-out to the maximum; that approach no doubt could have netted a massive gain in peak power, but it also would have dramatically narrowed the stock motor’s ultra-wide

powerband. Instead, Gatlin pursued a more moderate power increase throughout the entire rpm range by retaining the stock cam lift and duration, and by judiciously enlarging and reshaping the ports.

Gatlin was quick to point out that air-flow volume alone is not an adequate measure of how well a port works; a properly modified port will also maintain sufficiently high airflow velocity over the range of rpm the engine normally encounters. The ports required to feed a I400cc, 13,000-rpm Pro Stock engine, therefore, are not ideal for a street engine such as our 1186. With that in mind, Gatlin gave our Suzuki a high-velocity porting job that allows the engine to fill its cylinders much more quickly than it otherwise would, thereby precluding the need for highlift, long-duration cams.

And it works as promised. Since there is no loss of cylinder fill at low rpm (a condition that occurs with long-duration cams because of their late closure of the valves), the powerband on our 1186 is at least as wide as the stock engine’s, and much more potent. And the valve gear is as reliable as stock because it is stock (see accompanying story, page 74). The only thing Gatlin did here was to re-time the stock cams to give the intakes 103-degree lobe centers and the exhausts 105-degree centers.

We did, however, need to improve upon another intake restriction: the carburetors. Even on the stock engine, the original CV carburetors limit intake flow; on our 1186, they would have been hopelessly restrictive. So, we fitted a set of 40mm Mikuni RS-Series flat-slide carbs, which pass enough air to allow unimpeded flow through the modified ports. They also offer a wide range of adjustment. Right out of the box, the Mikunis were fairly close, and dialing them in to suit our motor’s demands required only lowering the needles to their leanest position, fitting a set of #135 main jets, and adjusting the accelerator pump to begin its delivery at one-quarter throttle.

On the exhaust side, Gatlin used a pipe of his own design, one that incorporates what he calls a “Tri-Y” header. According to Gatlin, this configuration aids performance at

virtually every useful rpm, partly because it maintains high gas-flow velocity, and partly because it manages pressure variations better than traditional 4-into-l systems.

Gatlin also paid particular attention to the combustion-chamber shape, one of the most critical factors in any high-performance engine. He says that the cylinder-head portion of the GSX-R’s chamber is superb and needs no modification, but he does slightly reshape the crowns of the MTC pistons to work more efficiently with his ports and the GSXR’s head. Gatlin says he has found that virtually all aftermarket pistons need to be modified to maintain the efficiency of the stock pistons. He feels that anyone who uses unmodified aftermarket pistons in a GSX-R is likely to encounter severe detonation problems or have an engine that

simply runs too hot.

What’s more, Gatlin contends that most hopped-up engines suffer from poor piston-ring seal, and that most aftermarket pistons aren’t as good as their stock counterparts in that respect, either. He is a student of the school of thought which professes that pistons should be sized to run in a cylinder that has been bored to the piston rings’ design diameter. In other words, you bore for optimum piston-ring diameter, not to achieve a specific piston clearance. He prefers MTC pistons because he has found them to be correctly sized for the piston rings, in addition to being lighter than stock—thereby reducing the loads on the connecting rods—and built of an alloy strong enough to promote good long-term reliability.

Cylinder finish also is critical for achieving optimum ring seal, requiring the bores to be round and straight to within a few ten-thousandths of an inch from top to bottom. So, once Gatlin has correctly matched the bores to the ring diameters, he hones his cylinders to a super-smooth finish. He claims his technique seals the gases in and the oil out of the combustion chambers for as many miles as does a stock engine’s cylinder finish. And to properly seal the important head-to-cylinder junction, Gatlin recommends and sells stock Suzuki head gaskets—the only kind that never seems to leak oil—that he has modified to accommodate the 2mm-oversize bores.

Among many other stock components found on our 1186 is the original ignition system. But although it delivers a spark hot enough to ensure reliable ignition, its advance curve is slightly retarded for our engine’s requirements. Gatlin easily overcame this shortcoming by installing an adjustable advancer from Dale Walker’s Holeshot Performance, which allows the static advance to be set within a 10-degree range. He adjusted ours to provide five degrees more advance than stock.

Gatlin had to deal with the stock GSX-R1 100’s ignition box, too. It has a built-in rev limiter that kills the spark at 11,500 rpm-too early for our 1186, which develops peak power at about 12,500 rpm and runs strongly to 13,000. The simple solution was to install a Suzuki GSXR750 ignition box, which has a

13,000-rpm rev limiter that lets us take full advantage of the engine’s power potential.

There are, however, a couple of drawbacks to raising the rev limit. One is that the 750’s ignition box has a list price of $271. Another is that the loads on the pistons, rings, rods and bearings are much greater at 13,000 rpm than they are at 11,500. The engine will withstand these additional loads but won’t prove as reliable as the stocker unless the GSXR’s original 11,500-rpm redline is observed.

Finishing off the powertrain package is a Holeshot Performance Electric Power Shifter, which allows fullthrottle, clutchless upshifts. A toggle switch turns the shifter on and off so it can be used only when needed.

Russell Performance Products SUPPLIERS 2645 Signal Jundry Hill, CA Ave. 90806 213/595-7523 Front-brake lines: $65 Rear-brake line: $38 Gatlin Racing Northstar Racing 1525 Endeavour Place, Suite K 3765 Roosevelt Rd. Anaheim, CA 92801 St. Cloud, MN 56301 714/563-0747 612/252-4465 or 800/950-4459 Stage III cylinder head: $795 Fiberglass bodywork: $680 Gatlin/MTC pistons: $346 Custom paint: approx. $1500 Bore and hone cylinder: $120 Modified head gasket: $50 Gatlin exhaust system: $389 Young’s Custom Cycle Seats Slotted cam sprockets: $29 1510 Howe Ave. Mikuni RS40 carburetors: $649 Sacramento, CA 95866 Holeshot advancer: $49 916/920-3513 Holeshot electric shifter: $179 Seat: $169 Back pad: $15 Fox Factory Inc. Zero Gravity 3641 Charger Park Dr. 5312 Derry Ave., Unit D San Jose, CA 95136 Agoura Hills, CA 91302 408/269-9200 818/597-9791 Twin Clicker shock: $545 Windscreen: $80

We were fully aware, of course, that our nine-second motor would need the assistance of a nine-second chassis, since even stock GSX-Rs are wheelie-prone during aggressive dragstrip launches. Under other circumstances, we would have opted for all the usual drag-race modifications—lowering the chassis, lengthening the swingarm, adding a wheelie bar—to keep the front wheel somewhere near the ground. But the 1186 was intended to be raced only in streetable trim, which meant that the comparatively small footprint of its DOT tires would significantly limit the available start-line traction. Knowing this, we decided that the only modification needed to insure quick, low-trajectory leaves was to lower the chassis.

We settled on a 2-inch drop at both ends, accomplished at the front by cutting a few coils off of each fork leg’s main spring, then installing a 2inch-long piece of pipe above the

top-out spring in each hydraulic damper. The rear end was lowered with a shorter-length shock specially made for us by Fox.

We then gave our GSX-R 1 186 a custom look by bolting on a complete set of fiberglass body panels from the

Body By Northstar division of Northstar Racing. These are near-duplicates of the stock panels, but offer large savings in both cost and weight. A complete Northstar body is six pounds lighter than its stock counterpart; its laminate construction offers exceptional strength, flexibility, and light weight; and its quality is excellent compared to other aftermarket body panels.

A smooth, gloss-white outer finish is standard on the Northstar panels, but gelcoat color options are available on request. This allows the application of stripes or graphics by means of paint or cut adhesive vinyl, enabling a custom look without the high cost of a custom paint job. Northstar does offer a custom painting service, though, an option we took advantage of for our GSX-R. Its beautiful finish was designed and applied through a joint effort between Northstar in St. Cloud, Minnesota, and Mike’s Custom Paint in nearby Annandale, Minnesota.

All of this assembling and painting and tuning was just a prelude to the main event; the posting of a nine-second quarter-mile. We decided that no one was more deserving of the honor of making that attempt than the bike’s architect, Jesse Gatlin.

But while we certainly chose the right rider, we picked the wrong day. The scorching temperatures during our runs at Carlsbad Raceway were high enough to drain some of the added horsepower that Gatlin had worked so hard to obtain. Still, he found enough residual oxygen in the California smog and sufficiënt grip in the GSX-R’s stock rear Dunlop Sportmax Radial to blaze the timing lights in 9.90 seconds at 141 miles per hour. Not too shabby. Wheelie bars and a racing slick would have easily nudged our “Gatlin Gun” into the low Nines.

But equipping our GSX-R in this way would have violated the spirit of the project: to build a nine-second machine that could be ridden daily— and enjoyably—on the street. And in that regard, the Cycle World GSXR 1 1 86 was an unqualified success.

Oh, sure, its ride was made a bit choppy by the shortened suspension, and we wouldn't recommend the bike for brushing up on your Kevin Schwantz imitations, particularly through right-handers; the cornering clearance on both sides has been reduced by the lowered chassis, and the right-side routing of Gatlin’s Tri-Y exhaust system further limits the degree of lean in that direction.

What the Suzuki isn't short on is prodigious horsepower. Obviously, its full-throttle, through-the-gears performance is awesome, as indicated by the quarter-mile numbers; but the roll-on acceleration is even more impressive, no matter what the speed, no matter what the gear. You just dial open the throttle, hang on, and make damned sure you have someplace to go—because in what seems like little more than a nanosecond, you’re there.

We’d like to take credit for this outstanding performance, considering that the bike’s mission was established by us at the very beginning. But Jesse Gatlin deserves the real applause here, since it was his skill and experience that turned our vision into reality. And even before the project was finished, he was already thinking about other tricks that could squeeze quicker E.T.s from the big GSX-R without damaging its streetability or reliability.

Maybe ol' Gottlieb Daimler wouldn’t have understood, but we do. Perfectly. 13

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

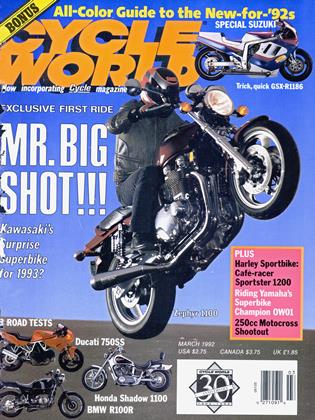

March 1992 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

March 1992 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

March 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1992 -

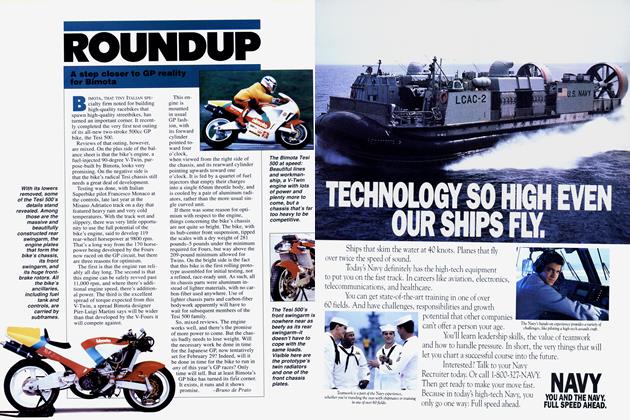

Roundup

RoundupA Step Closer To Gp Reality For Bimota

March 1992 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupAmerica 1: Gold-Plated Superbike

March 1992 By Jon F. Thompson