The Bicycle Connection

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

A FEW MONTHS BACK, I WROTE A COLumn about Italian motorcycles, suggesting that their owners might also be vulnerable to the charms of Italian bicycles, and, in fact, have them hanging on their apartment walls.

Amazingly, I got half a dozen letters from readers who accused me of window-peeping and said, in effect, “How did you know I had a Colnago 14-speed hanging over the fireplace?”

I have a lot of vices, but peeping through windows is not one of them, except in those cases where I lock myself out of my own house. If I did window-peek, however, a good bicycle over the fireplace would be a likely object of my riveted attention.

Seems I’m in the market again for a bicycle and have been prowling around bike shops-for the first time since I bought my 27-pound, yellow-framed, 10-speed Raleigh Record in 1971. I’m probably deluding myself, but I have this idea that a modern, finely crafted lightweight bicycle with round wheels and a plurality of spokes will encourage me to ride more. And why would I want to ride more?

Well, basically, so I can continue to fit into the black Buco horsehide motorcycle jacket I bought in 1966 and have worn ever since. Or, to put it more bluntly, if I gain two more pounds my jacket may explode, wounding a lot of innocent bystanders with zipper fragments. So bicycling has become part of my 14-point summer-fitness program. The other 13 points involve Mexican food, margaritas and 11 different brands of dark beer.

There’s always running, of course. I’ve been running a fair amount this summer, but have to admit I don’t like it much. It’s very hard to get off a motorcycle, change clothes and go running on the same rural roads where you were recently riding. It’s one of those sobering, back-to-reality jolts, like bailing out of a P-38 Lightning and finding yourself afoot in downtown Berlin, or crashing a racebike and walking back to the pits. How far the gods have fallen....

Bicycles soften the contrast a little. They aren’t motorcycles, but at least they provide a cooling breeze, a bracing sense of real forward motion, an occasional change of scenery and (like motorcycles) the satisfaction that you are cheating physics by getting a little more out of the inertial bank account than you are putting in. Bicycling can give you the illusion you have wings on your feet, while running makes me feel as if the Mafia tied cement blocks to my ankles during the night and then forgot to throw me into the East River. Mostly, it’s just too slow.

Also, most of us who ride motorcycles started out on bicycles. In fact, I don’t know anyone who first learned to balance a two-wheeler by taking a test ride on a Ninja, or by installing training wheels on a GSX-R1100 (“You’ve got it, Jimmy! Now downshift, get your knee out and wick it up!”). We ride bicycles first, and they teach us a lot.

We learn, among other things, to have faith in those two big gyroscopes, to lean into corners, to avoid sand and wet leaves, to lube our chains, to patch tires, to operate gasstation air hoses, to adjust handlebars, to visit distant girlfriends, to pick gravel out of our skin and-most important of all-to avoid the crossbar during jumps.

It has occurred to me, too, that our early choices in bicycle model and design may have a later influence on what sort of motorcycles we buy. Some of my younger riding pals, like Andy Bornhop, got a head start on dirtbikes because of BMX competition, which did not exist in the Eisenhower years of my own pre-adolescence. Kids in my generation had to take standard balloon-tired bicycles and strip them down to provide the illusion of race machinery, the main role models being Harley flat-trackers or Triumph TT bikes.

There was no other equipment, of course, no helmets or motocross riding gear. All racing was done in Keds, blue jeans, white T-shirts and baseball hats (Milwaukee Braves, in this case). Imagination was everything.

The week I learned to ride a bike, my dad fulfilled a standing promise and bought me a used bicycle. It turned out to be a purple, 26-inch English racer with skinny tires, Brooks saddle and tool bag, hand brakes and a Sturmey-Archer threespeed shifter on the handlebar. The brand? Triumph, no less.

Not to overplay the “as the twig is bent” angle too much, but this accidental purchase may have had some influence on my later choices in motorcycles-Triumph lust, English sympathies, a taste for lightweight, narrow, sporting roadbikes without a lot of clutter on them.

At the time my dad bought the English racer, of course, these preferences were not yet ingrained, and I was secretly disappointed. What I really wanted was a big, solid, balloon-tired American paper-boy bike like the deluxe Schwinn that belonged to my friend Rodney Spors. Rodney’s bike had a fake gas tank with a horn button in it, a big chrome headlight, a pseudo-springer fork, handlebar streamers, a luggage/passenger rack, mudflaps and twin sidebaskets with reflectors on them. A Fifties dream bike.

This secret admiration for Rodney’s bike may, in turn, explain why I recently bought a Harley-Davidson Electra Glide Sport. A little revenge factor here? Maybe. Perhaps a leftover yearning from growing up around bicycles that were, essentially, trying to be Indians and Harleys for the young.

Even though I’m a little too old for a paper route and most of my bikes now make their own engine noises, it seems that skinny English racers and great big balloon-tired Schwinns continue to have their respective places on the road, and in the imagination. The beauty of adulthood is the freedom to sample both, without asking your mom and dad. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter To Willie G.

November 1992 By David Edwards -

TDC

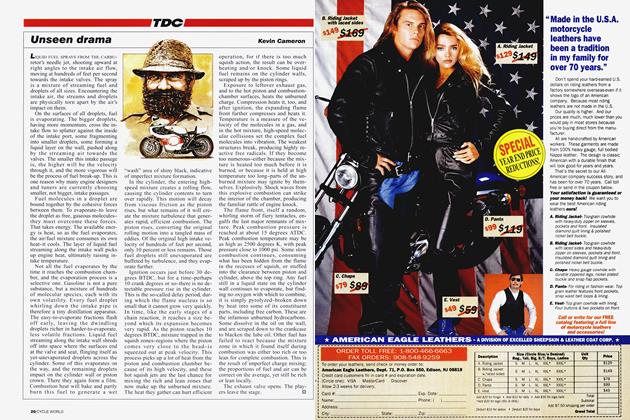

TDCUnseen Drama

November 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupFirst Look: Kawasaki 1993

November 1992 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupWorld's Fastest Refrigerator

November 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Radd Sport-Tourer

November 1992 By Jon F. Thompson