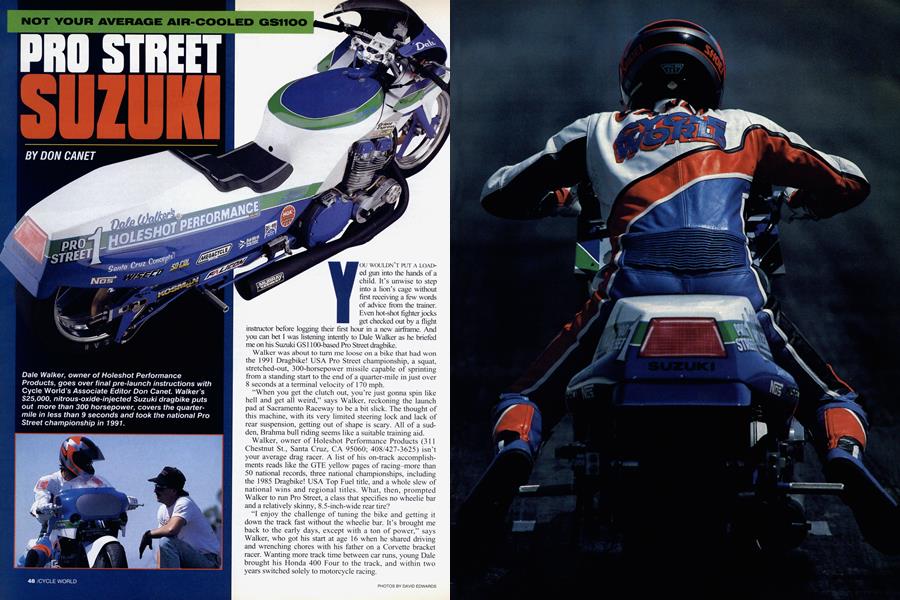

PRO STREET SUZUKI

NOT YOUR AVERAGE AIR-COOLED GS1100

DON CANET

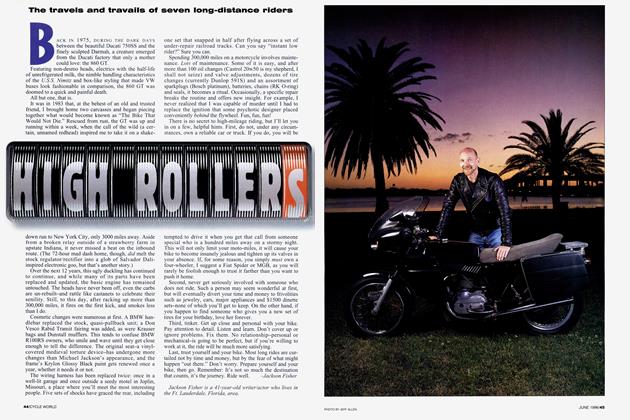

YOU WOULDN'T PUT A LOADed gun into the hands of a child. It's unwise to step into a lion's cage without first receiving a few words of advice from the trainer. Even hot-shot fighter jocks get checked out by a flight instinctor before logging their first hour in a new airframe. And you can bet I was listening intently to Dale Walker as he briefed me on his Suzuki GS1100-based Pro Street dragbike.

Walker was about to turn me loose on a bike that had won the 1991 Dragbike! USA Pro Street championship, a squat, stretched-out, 300-horsepower missile capable of sprinting from a standing start to the end of a quarter-mile in just over 8 seconds at a terminal velocity of 170 mph.

“When you get the clutch out, you’re just gonna spin like hell and get all weird,” says Walker, reckoning the launch pad at Sacramento Raceway to be a bit slick. The thought of this machine, with its very limited steering lock and lack of rear suspension, getting out of shape is scary. All of a sudden, Brahma bull riding seems like a suitable training aid.

Walker, owner of Holeshot Performance Products (311 Chestnut St., Santa Cruz, CA 95060; 408/427-3625) isn’t your average drag racer. A list of his on-track accomplishments reads like the GTE yellow pages of racing-more than 50 national records, three national championships, including the 1985 Dragbike! USA Top Fuel title, and a whole slew of national wins and regional titles. What, then, prompted Walker to run Pro Street, a class that specifies no wheelie bar and a relatively skinny, 8.5-inch-wide rear tire?

“I enjoy the challenge of tuning the bike and getting it down the track fast without the wheelie bar. It’s brought me back to the early days, except with a ton of power,” says Walker, who got his start at age 16 when he shared driving and wrenching chores with his father on a Corvette bracket racer. Wanting more track time between car runs, young Dale brought his Honda 400 Four to the track, and within two years switched solely to motorcycle racing.

"I've always had the natural clutch hand," Walker says. And unlike most big-time drag racers today, Walker eschews the use of modem riding aids such as a stutter box, a device that limits engine revs to a preset rpm during staging; or a shift light, a large bulb mounted by the instrument panel that signals when to shift; or a thumb-actuated air shifter. “I like having to ride the bike, shifting with the foot, working the clutch. I like watching the tach, not one of those lights,” he says.

Walker’s Kosman-chassied Suzuki started the ’91 season as a turbocharged Kawasaki, but mid-season politics led to the installation of a Suzuki motor in the highly modified KZ1000 frame, then clothing it with a GSX-R-styled Pro Stock body. The original racebike was powered by a 1394cc, turbocharged, two-valve Kawasaki motor, but Walker didn’t feel it was competitive in the balls-out, no’bar class and successfully lobbied the series promoter for permission to use nitrous-oxide injection in conjunction with the turbo. Two races later, having spent plenty of time, money and effort getting the package dialed-in, Walker nearly beat the reining class champ at a national in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

“Right after that, I was told that I could no longer use the nitrous, so that’s what fired me up to put the Suzuki motor in my bike,” says Walker, who was by then the series point leader. He and crew chief Farrell Vaughn set forth rebuilding a 1982 air-cooled GSI 100E motor. Bob Wirth, a master fabricator and welder whose services Walker had enlisted many times over the years, cut the Kawasaki engine mounts out of the frame and fitting the Suzuki motor.

Walker points out that when built to the extremes allowed by Pro Street rules, the old-style GS bottom end offers greater strength and reliability than the lighter GSX-R-series engines, which were built with roadracing, not drag racing, in mind. As a testimony to this claim, Walker’s engine uses stock GS1100 cases, connecting rods and roller-bearing crankshaft (though this is welded, polished and balanced by Falicon). Power is fed through a billet clutch hub, and an MRE centrifugal-lockup device is used to eliminate clutch slippage. The manually shifted, five-speed transmission makes use of heavy-duty first and second gears, and a beefed-up output shaft, all from Orient Express. The gears’ engagement dogs have been undercut by Fast by Gast for more positive engagement.

Walker uses a Holeshot Performance Electric Power Shifter-a product he developed 10 years ago-to speed upshifts and to prevent bent valves or a blown motor in the event of a missed shift by killing the ignition whenever the transmission is between gears. The momentary ignition kill also releases the load on the engagement dogs, which allows the shift to be made without using the clutch or backing out of the throttle.

Walker’s motor has a bore size of 85mm-far larger than the stock cylinder block will allow. A Vance & Hines big block is used along with Wiseco forged aluminum pistons, bumping displacement to 1497cc, with a compression ratio of 12.5:1.

Vaughn, who now handles all of the Holeshot Performance cylinder-head porting, reworked the ports of the GS1100 head. Valvetrain components consist of oversized, stainless-steel valves, HP Pro springs and cups, and titanium valve-spring retainers. A set of Megacycle cams with .430 inch of lift and 269 degrees of duration on the intake, and .420 lift with 256 duration on the exhaust complete the package.

Carburation is handled by a set of Vance & Hines 39mm Mikuni Cone carbs, with additional fuel and nitrous oxide being injected by an NOS system. Strong spark is a must for a high-output nitrous motor, so Walker uses a BHP Mallory magneto, belt-driven off the crank.

Walker prefers the Murray Engineering Pro Sidewinder 4into-1 exhaust system, which features 1.75-inch outsidediameter headpipes and a hand-fabricated, high-velocity collector, all of which play a vital role in extracting the engine’s claimed 225 horsepower without nitrous, and 325 horsepower when “on the bottle.”

Having tons of power on tap requires a chassis that can deal with the load. Walker’s Kawasaki KZ frame has been extensively modified by Kosman Racing in San Francisco, California. Kosman retained only the KZ’s engine cradle, using 4130 chrome-moly tubing to completely reconstruct everything else. The frame conversion duplicates Pro Stock geometry, with a wheelbase stretched to 72 inches, a raked steering head, a fuel tank/backbone, a much wider and longer swingarm, and a lower rear subframe that allows use of one-piece Custom FRP fiberglass bodywork. Kosman components are used throughout, including modular wheels, brakes, drag fork, countershaft-sprocket support plate, foot-

pegs and battery box.

With the cost of a complete Kosman Stage-1 rolling chassis right at $9500 and a competitive Holeshot Performanceprepped motor running easily as much, racing at this level is much more than a hobby. “Racing pretty much became my job. I race for my business now,” says Walker, who competed sporadically the four years prior to the ‘91 season, concentrating mainly on his company and test-riding for Kosman Racing. “It was time to make my name current again. My goal is to make sure my customers know that Dale Walker isn’t a has-been, that he can still come out and do it.”

And now it was my turn to go out and do it aboard Walker’s intimidating machine.

“Yeah, a few guys have looped a Pro Street bike over on its back,” says Walker in response to my query concerning personal safety. Thus, my first passes on the Suzuki will be made with the NOS system disarmed, so I can get a feel for the bike before trying for any real numbers. My initial, 12.37-second run, complete with a tentative launch and a fumbled shift to second, isn’t very impressive and would put me at the short end of a speed contest with a stock Ducati 750SS. Thirty pounds of ballast in front of the motor semiassure me that the thing isn’t going to rear up and drag me Shoei-first down the track, so 1 get more aggressive over the next four runs, breaking the 10-second barrier with a 9.45second pass at 147 mph.

The quickest production bike Cycle World has tested was the 1990 Kawasaki ZX-1 1, which ran 10.25/137, so Walker’s Suzuki clearly is making power, even without the nitrous. And high-speed stability is very good, as you would expect from a bike with the wheelbase of a Mayflower moving van. But I’m still uneasy. It launches so hard that I’m having trouble getting my feet back to the swingarm-mounted footpegs in time to make the shift into second. When I do, I’ve got to contend with the awkwardly placed shift lever. On one run, I think I’ve got things right, only to have the toe of my left boot snag the pavement and bump the shifter, popping the tranny into neutral and killing the motor.

Even so, Walker figured it was time to crack open the valve on the blue nitrous bottle and take a shot at getting into the 8s. First, he calibrated the NOS jetting down some-the motor would be delivering “only” about 280 horsepower-due to the track conditions and my inexperience with the bike. And Walker bypassed the usual NOS activating system that started the juice flowing as soon as the clutch was home in first gear. Instead, I’d be punching a button on the left handlebar, and only after I’d notched into third gear.

With torque the Queen Mary would be proud of, launch-

ing was relatively simple: Revs held at 4500 rpm and a quick clutch feed was all that was required to make a clean, smooth leave. Things then got interesting as the Suzuki squirmed on its Goodyear slick, hunting for grip as I worked up through the lower gears. Into third gear, I mashed the nitrous button and held my breath. It was like kicking in an afterburner for the remainder of the run. The increase in top-end speed was simply incredible, the bike pulling a gear higher through the speed trap at the far end of the quarter. I was pumped even before I found out the result, an 8.98-second run at 165 mph. Jazzed, I made one more pass with the juice, turning a slightly slower 9.01, but with a faster 167-mph trap speed. It’s easy to see how drag racers get hooked on this nitrous oxide stuff.

The day wouldn’t be complete without Walker showing us how it’s really done. With its owner at the controls, the bike lunged out of the hole, bogged briefly, then the NOS-triggered by the clutch-lit off. Walker rocketed away, like a heatseeking missile launching from the wingtip rail of an F-16 fighter, posting an 8.41/171, just shy of the bike’s best run of 8.22/171 at Phoenix Raceway Park during the season finale. Walker had a flame-out on his next pass when the bolt securing the magneto pulley to the end of the crankshaft sheared off, resulting in no damage other than killing the spark and our fun for the day.

My brief stint aboard this national championship Suzuki left me with an insight into the addiction that afflicts all drag racers. Nothing I’ve done in motorcycling packs as much intensity into so little time. It’s a rush, and I’m already going through withdrawal symptoms. But since Dale Walker is a parts pusher who deals in speed, my fix is just a bruised bank account and a phone call away. Œ

“WHEN YOU CLUTCH OUT, YOU’RE JUST GONNA SPIN LIKE HELL AND GET ALL WEIRD.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue