Coming of Age

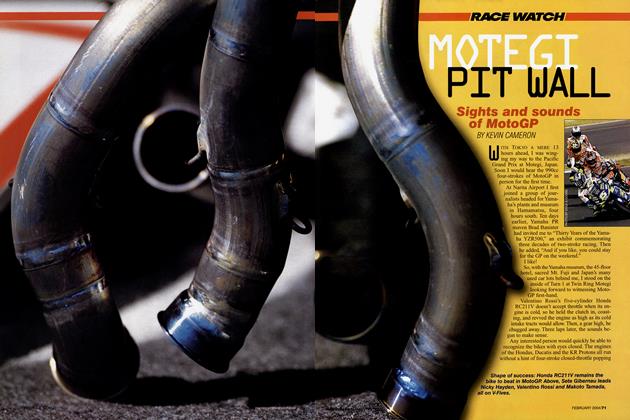

RACE WATCH

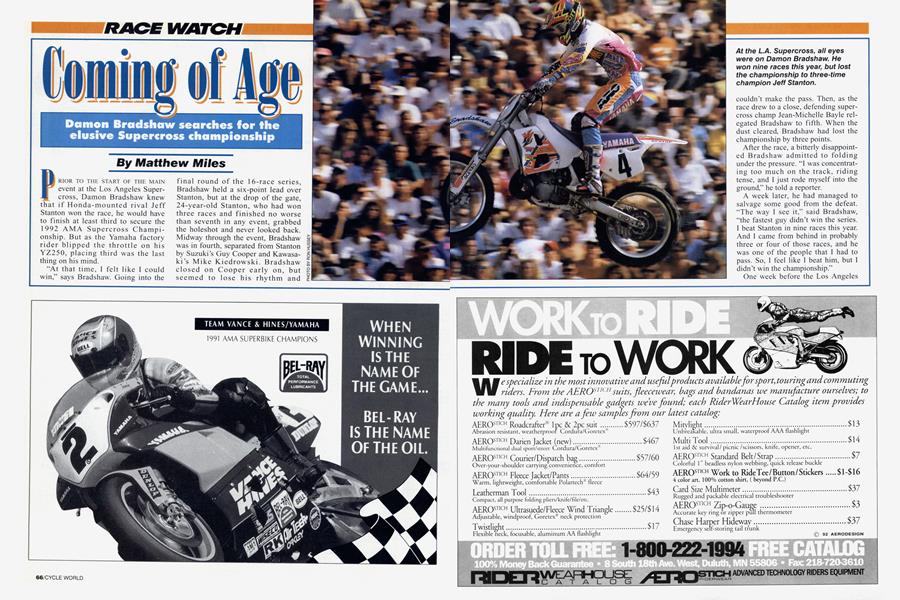

Damon Bradshaw searches for the elusive Supercross championship

Matthew Miles

PRIOR TO THE START OF THE MAIN event at the Los Angeles Supercross, Damon Bradshaw knew that if Honda-mounted rival Jeff Stanton won the race, he would have to finish at least third to secure the 1992 AMA Supercross Championship. But as the Yamaha factory rider blipped the throttle on his YZ250, placing third was the last thing on his mind.

“At that time, 1 felt like I could win,” says Bradshaw. Going into the final round of the 16-race series, Bradshaw held a six-point lead over Stanton, but at the drop of the gate, 24-year-old Stanton, who had won three races and finished no worse than seventh in any event, grabbed the holeshot and never looked back. Midway through the event, Bradshaw was in fourth, separated from Stanton by Suzuki's Guy Cooper and Kawasa ki's Mike Kiedrowski. Bradshaw closed on Cooper early on, but seemed to lose his rhythm and

couldn’t make the pass. Then, as the race drew to a close, defending supercross champ Jean-Michelle Bayle relegated Bradshaw to fifth. When the dust cleared, Bradshaw had lost the championship by three points.

After the race, a bitterly disappointed Bradshaw admitted to folding under the pressure. “I was concentrating too much on the track, riding tense, and I just rode myself into the ground,” he told a reporter.

A week later, he had managed to salvage some good from the defeat. “The way I see it,” said Bradshaw, “the fastest guy didn’t win the series. I beat Stanton in nine races this year. And I came from behind in probably three or four of those races, and he was one of the people that I had to pass. So, I feel like I beat him, but I didn’t win the championship.”

One week before the Los Angeles event, at an outdoor motocross in Buchanan, Michigan, Bradshaw damaged the anterior cruciate ligament in his left knee. At the time, he didn’t know the full extent of the injury, but decided to ride anyway, in defeat, Bradshaw refused to use the injury as an excuse.

“1 really didn’t even think about my leg. It didn’t bother me. Obviously, it just wasn’t my year to win the championship, but I don’t know how much closer I can get,” he said.

Bradshaw won five out of the first six supercross races this year, but the near-record-breaking effort came to a halt in Florida, when Stanton won his fourth consecutive Daytona Supercross. After finishing second at Daytona, Bradshaw encountered numerous problems, failing to reach the podium in the next three races. He> did, however, manage to score important points in nearly every event, with the only exception being Indianapolis, where he crashed heavily while chasing Stanton.

“If we look at the series, there’s one race that really cost him the most, and that was Indianapolis,” says Yamaha’s Motocross Team Manager Keith McCarty. “Put him in 15th place, that could have him winning the championship. It’s just one of the pitfalls of racing.”

Like most MX stars, the 20-year-old Charlotte, North Carolina, native began his racing career at an early age.

“I started riding when I was 3, and racing when I was 4. My dad told me that as soon as I could ride a bicycle without training wheels, he’d buy me a motorcycle, and he did what he said. My parents were always there for me 110 percent,” Bradshaw says.

He quickly established himself as a force in the minibike ranks, and by 1988, had moved up to big bikes and was showcasing his talents internationally: “I won my first Supercross when I was 15, in Canada. Then I won the Japanese Supercross in Osaka. That was a big turning point for me.”

In 1989, at age 16, Bradshaw signed a three-year factory contract with Yamaha. That year, he won the Eastern Regional I25cc Supercross Championship, and placed second in the 125 supercross and 125 national outdoor series. He also notched a trio of first-place finishes at events in Paris, Milan and Toronto, and repeated as the Osaka Supercross winner.

Aside from a handful of international appearances, Bradshaw devoted the next two years to the U.S. supercross and 250cc national outdoor championships. In 1990, he took five Supercross wins, the Mount Morris 250 National and his third Japanese Supercross victory. In addition, he was a member of the winning Motocross des Nations team. Last year brought a second-place finish in the supercross series and a third overall in the 25()cc outdoor program. Clearly, Bradshaw had shed his early image of a highly talented, but in-> consistent rider, even if a major championship continues to elude him.

“Riders need competition,” says McCarty. “Last year, Bayle was a major part of that competition. This year, I think Damon brought himself to that level and maybe beyond. At this point, nobody’s won the number of races that Damon has won in a single season. You can say he’s in his prime right now, but 1 think he’s just rising to the occasion.”

Undeniably one of the most aggressive riders around, Bradshaw was penalized for rough riding at this year’s Las Vegas Supercross. Attempting to pass Kawasaki’s Jeff Matiasevich for third place, Bradshaw and Matiasevich collided and both riders went down. After reviewing the incident, the AMA fined Bradshaw $1500.

“Matiasevich was committed to his line and the contact that Damon made with him was, we felt, unjustifiable,” says the AMA’s Roy Janson. “We looked at a variety of (camera) angles, and fined Bradshaw the equivalent of the prize money he would have earned that night for that position.”

McCarty strongly opposes the AMA’s decision.

“I think it was a bad decision. It’s very inconsistent with what they’ve done in the past. 1 don’t consider what Damon did to be a blatant intent to harm somebody. I’d look at it as a very aggressive block-pass. Damon’s an aggressive guy.”

“You do unto others what you want done unto you,” says Bradshaw. “I automatically know when I come up on Matiasevich how I’m going to pass him. It’s going to have to be aggressive, unless it’s a racetrack where> there’s a lot of room to pass on. Outdoors, I don’t have any problem passing him. Indoors, it’s going to take some slamming. With other guys, it might be different.”

“I’m not in any way, shape or form wanting to see the type of riding where people are ramming each other for the win,” adds McCarty. “But some of the tracks that we’re forced to ride on leave you no other choice but to do these types of things. If the AMA wants to lay out the fines to the riders, then they should be very careful that the racetracks have more than one line in every passing section. These guys get paid to ride, and they get paid more to win.”

For the rest of this year, Bradshaw will contest the second half of the I25cc national series rather than ride the 500cc nationals on a modified, air-cooled WR500 cross-country bike, as he did last year.

“The WR wasn’t really aimed as a motocross bike,” says McCarty. “Damon has been riding the 125 throughout the year at certain test sessions and he was pretty happy with the way it ran. Fie thought that it would be kind of a fun deal for him, to show everybody what our 125s are capable of.”

Though Bradshaw’s contract expires at the end of the year, he’ll likely continue to race for Yamaha.

“I’m happy where I’m at. I’ve had other offers, but I hope to be at Yamaha. They’ve been with me both up and down. To have that support means a lot,” he says.

Bradshaw says he will race as long as he is competitive. When his racing career does come to a close, he hopes to expand his interests outside of motocross. “I enjoy horses. I’ve got a small business started now raising paint horses. Hopefully, that business will be on its feet by the time I’m done racing. But for now, I want to continue what I’m doing,” he says.

Nothing is ever certain, especially in racing, but if Damon Bradshaw continues at his current pace-if he can get over the disappointment of the 1992 season-look for him to win many races and championships in coming years.

A quote given after the L.A. Supercross loss is an indication that he is already planning for next year. “I may have lost the championship,” said Bradshaw, “but I learned a lot today.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue