WRINGING OUT THE 250cc STUMP-JUMPERS

CW COMPARISON

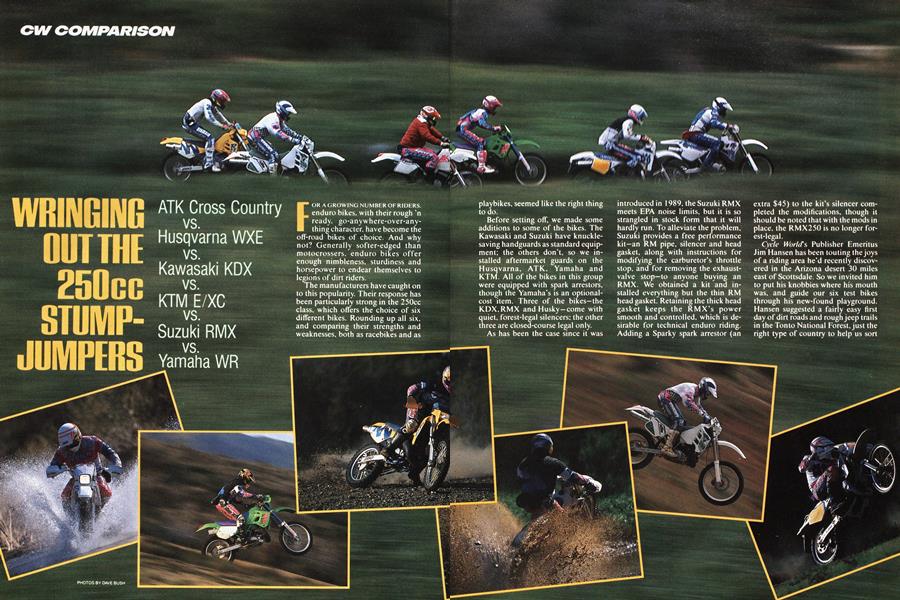

ATK Cross Country VS. Husqvarna WXE VS. Kawasaki KDX VS. KTM E/XC VS. Suzuki RMX VS. Yamaha WR

FOR A GROWING NUMBER OF RIDERS, enduro bikes, with their rough 'n ready, go-anywhere-over-anything character, have become the off-road bikes of choice. And why not? Generally softer-edged than motocrossers, enduro bikes offer enough nimbleness, sturdiness and horsepower to endear themselves to legions of dirt riders.

The manufacturers have caught on to this popularity. Their response has been particularly strong in the 250cc class, which offers the choice of six different bikes. Rounding up all six. and comparing their strengths and weaknesses, both as racebikes and as

playbikes, seemed like the right thing

to do.

Before setting off, we made some additions to some of the bikes. The Kawasaki and Suzuki have knucklesaving handguards as standard equipment; the others don’t, so we installed aftermarket guards on the Husqvama, ATK, Yamaha and KTM. All of the bikes in this group were equipped with spark arrestors, though the Yamaha's is an optionalcost item. Three of the bikes—the KDX.RMX and Husky—come with quiet, forest-legal silencers; the other three are closed-course legal only.

As has been the case since it was introduced in 1989, the Suzuki RMX meets EPA noise limits, but it is so strangled in stock form that it will hardly run. To alleviate the problem, Suzuki provides a free performance kit-an RM pipe, silencer and head gasket, along with instructions for modifying the carburetor’s throttle stop, and for removing the exhaustvalve stop—to anyone buying an RMX. We obtained a kit and installed everything but the thin RM head gasket. Retaining the thick head gasket keeps the RMX's power smooth and controlled, which is desirable for technical enduro riding. Adding a Sparky spark arrestor (an extra $45) to the kit’s silencer completed the modifications, though it should be noted that with the mods in place, the RMX250 is no longer forest-legal.

Cycle Worlds Publisher Emeritus Jim Hansen has been touting the joys of a riding area he’d recently discovered in the Arizona desert 30 miles east of Scottsdale. So we invited him to put his knobbies where his mouth was, and guide our six test bikes through his new-found playground. Hansen suggested a fairly easy first day of dirt roads and rough jeep trails in the Tonto National Forest, just the right type of country to help us sort

out each bike’s jetting and suspension settings.

On day two. John Miller, an A enduro rider and the owner of Sunnyslope H onda in Phoenix, would lead us around his tight and technical, high-desert practice loop south of Wickenburg, Arizona. Our last day of riding would be in the area of the Verde River, where sandwashes run for miles through rocky canyons.

Seven miles into the desert hills on the first day, terrible screeching sounds from the RMX’s clutch stopped us in our tracks. To our dismay, we discovered the bike had been set up by Suzuki with its transmission dry. One rider was dispatched to get oil, a quart of which stopped the squealing. Two miles deeper into the mountains, it was the KTM’s turn to gives us trouble, the bike taking on the appearance of a steam engine. A small, air-bleed screw for the liquidcooling system had fallen out. This departure was quickly followed by the evacuation of the engine's coolant. A sidecover screw w'as threaded into the head and the coolant supply refreshed from a nearby creek.

After these near-disasters, the rest of day one proved less frustrating and a lot more fun; we rolled miles on the test bikes, switching mounts throughout the long day.

On day two, we met Miller at the turnoff to his favorite riding spot, which proved to be a highly technical network of trails. Miller explained; “Most of my riding buddies think I’m crazy. I like to take the hardest possible way, and I try to change the rhythm of the trail as often as possible. I’ve been riding this 30-mile loop three times a week to get in shape for the enduro season.”

Three hours later, our group of testers, battered and bruised, finished Miller’s loop. “1 didn't know a desert trail could be so challenging and tight.” one of the riders exclaimed. Another, more used to the rigors of Pro motocross, was flat on his back. “Is this kind of riding supposed to be so exhausting? 1 don't think I could have walked over some of those trails,” he said.

Day three was a lot easier, and provided us with another facet of the broad usage enduro bikes are subjected to. The sandwashes along the Verde River gaves us a chance to sample the bikes’ high-speed manners, and casual exploration along side trails told us how' each machine fared as a playbike.

Then it was time for everyone to evaluate the bikes and place each in order of its competence at a wide variety of off-road uses.

Most agreed that the KTM 250 E/ XC has the most comfortable, best all-around suspension. Bumps of all sizes simply disappear, yet for all that softness, the KTM seldom bottoms in high-speed G-outs. The Austrian bike also exhibits a great balance between light handling and high-speed stability. The E/XC's engine is as impressive as its chassis. It's as responsive as that of a motocross bike—and as powerful —but, somehow this power is transmitted to the bike’s rear wheel without undue wheelspin.

With its wonderful suspension, sure handling and zappy engine, the K TM is a blast to ride, and is our favorite in this group of six bikes.

Hot on the KTM’s rear wheel is the Husqvarna 250WXE. The Husky has an amazing engine with a powerband like that of an electric motorsmooth and linear from idle to redline. The bike isn’t as fast as the K TM, but heavy flywheel effect provides the best rear-wheel traction of this bunch. No matter how slippery, rocky or muddy the going, the Husky will get you through.

Additionally, the Husky’s superquiet exhaust doesn’t offend other

ATK

250 CROSS COUNTRY

$4375

HUSQVARNA

250WXE

$4150

KAWASAKI

KDX250

$3999

KTM

250EXC

$4199

SUZUKI

RMX250

$4099

YAMAHA

YZ250WR

$4199

trail users and doesn’t strangle the engine’s power. The downside is that the WXE is a bit heavy, and its steering is a little slow for tight trails. But its high-speed stability is excellent, even in sand. Fitted with factorystock White Power suspension, both ends of the Husky work well, though on small bumps the bike’s suspension is not as plush as the KTM’s, which uses the same style White Power components, though valved differently. We voted the Husky as second to the KTM, but had our testing taken place in the South or the East,

where mud and slime are the rule, things might have been different.

The other four bikes in this group trail first and second place by quite some distance. All are solidly built and bristle with quality hardware, strong disc brakes, reliable engines and well-thought-out detailing. But where the KTM and Husky are outstanding in stock form, the other four would benefit from fine-tuning or redesign. We've listed them in alphabetical order, explaining each bike’s strong and weak points.

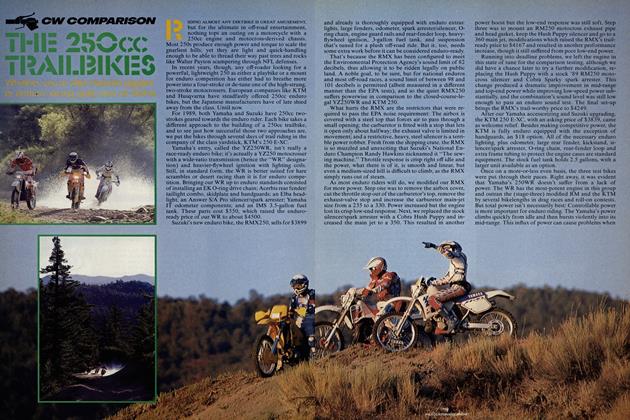

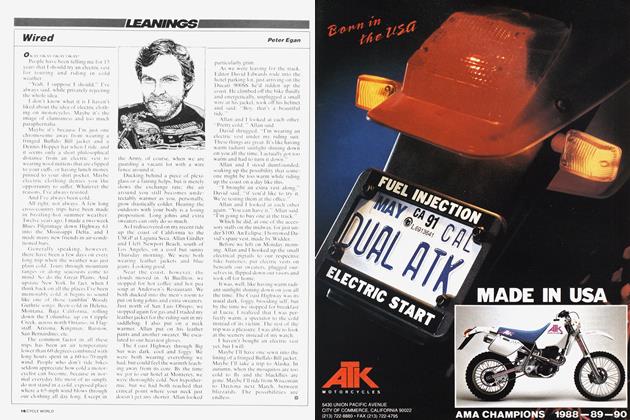

ATK's 250 Cross Country features an American-make, heli-arc-welded, nickel-plated, chrome-moly steel frame and swingarm. It has excellent White Power suspension, a unique countershaft-mounted rear disc brake and a brake pedal that pivots at its front, virtually eliminating the possiblity of it snagging on trail brush or tree roots. At 222 pounds dry. the ATK is the lightest bike of the group, a fact that’s instantly apparent when blasting down a tight, rough trail — where the Cross Country handles with the ease and agility of a 125. And the ATK has excellent highspeed manners in sand and across deep whoops.

Unfortunately, this bike’s aircooled, rotary-valved engine is saddled with a narrow powerband.

Horsepower this motor has, but the transition from its poor low-end to a strong midrange burst is lightswitch quick, and then it’s over almost as quickly as it started. With a wider power spread, the ATK would be right up there with the KTM and the Husky.

Kawasaki's long-awaited KDX250 got our attention as soon as it hit the scales. At 258 pounds without fuel, the KDX is 30 pounds heavier than a KX250 motocrosser, and 36 pounds heavier than the ATK. The steelframed KDX—in actuality, a modified Japanese-market dual-purpose

bike—is a big. Open-class-sized motorcycle. On the trail, the Kaw feels as heavy as it is, and its steering is vague. With the fork-tube caps flush with the top triple clamp, the KDX’s front wheel absolutely won’t stay on a narrow trail, the front tire constantly wandering to and fro, bouncing off rocks and bushes. Raising the fork tubes a half-inch helped some, but the bike is still spooky to ride on narrow paths, and is clumsy in tight turns.

The report on the Kawasaki’s engine is a bit more positive. It has good low-end power, and the transition to its strong midrange is gentle. There’s decent top-end power and the exhaust is quiet. But the KDX’s suspension is merely okay-there’s some harshness and the fork bottoms easily when the bike is ridden hard. A re-think of this bike’s suspension and steering geometry is in order, as is a weight reduction.

Enduro star Randy Hawkins has won big-time on his factory Suzuki RMX250, but that fact doesn't ensure that an average guy will like the RMX. Most of CWs test riders didn’t. There’s no disputing the RMX's ability to effortlessly and quickly carve its way through the tightest terrain. Every control on the RMX works with buttery smoothness, it has good suspension and brakes and, courtesy of Suzuki’s nocost hop-up kit, its engine can be tuned to full-on MX standards, or for a smoother, more subdued powerband, the option we chose.

But enduro riding is more than just tight trails. Sometimes it’s necessary to twist the throttle hard to make up time in fast sections or in sand washes. In such areas, the RMX has trouble. In tight, sandy corners, its front end tucks, and at higher speeds.

whether in sand or not, the RMX’s handling often changes without warning from a fairly controlled busyness to a violent headshake.

That leaves the Yamaha WR250. The WR isn't a true enduro bike—we knew that going in—but it’s the closest thing Yamaha makes, and many people have modified WRs for enduro use. With its potent, motocrosstuned engine and wide-ratio transmission, the WR is a good harescrambles bike, and, with taller gearing and a larger fuel tank, a great desert bike. But it’s a handful on a technical, rock-strewn enduro trail or a slippery fireroad. The engine needs more flywheel weight to smooth its power rush and to reduce rear-wheel spin, and the loud silencer should be drop-kicked and replaced with a much quieter one.

To its credit, the WR has great high-speed stability, neutral handling in the crooked stuff, a strong frame and swingarm, good brakes and compliant suspension. Adding a flywheel weight, a quieter silencer and the enduro accessories necessary for your area could be worth the effort and expense.

But if the idea of buying a new enduro bike and immediately having to modify it doesn't set well with you, there’s a very easy solution. Buy a KTM 250 E/XC or Husqvarna WXE 250, add premix and go riding.

And of those two, we’d lean heavily towards the KTM. El

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSpeed Thrills

August 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeStatus Miles

August 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsWired

August 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1991 -

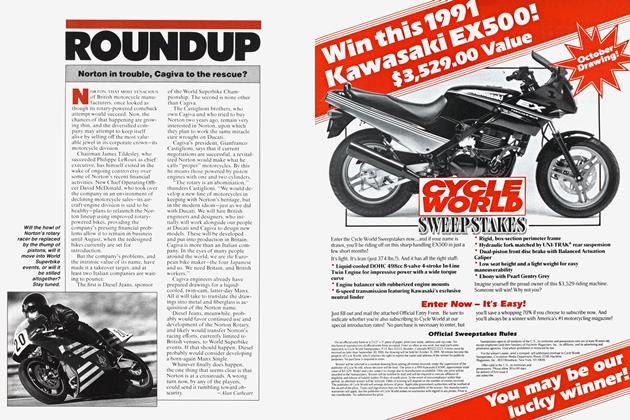

Roundup

RoundupNorton In Trouble, Cagiva To the Rescue?

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

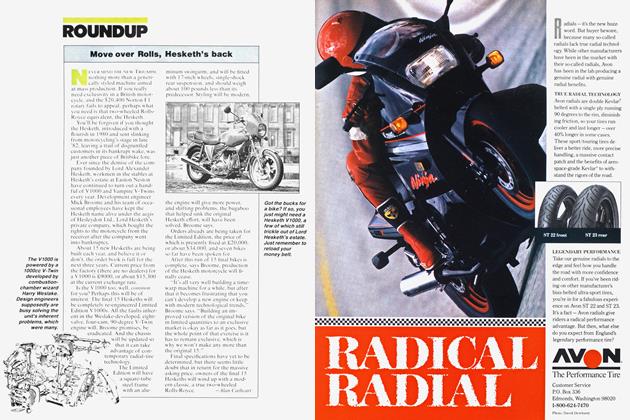

Roundup

RoundupMove Over Rolls, Hesketh's Back

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart