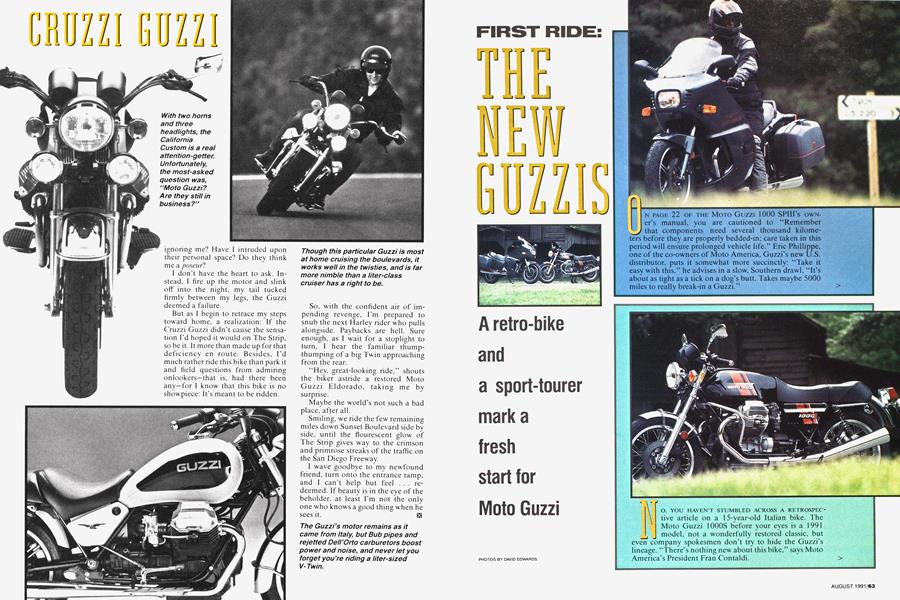

THE NEW GUZZIS

FIRST RIDE

A retro-bike and a sport-tourer mark a fresh start for Moto Guzzi

ON PAGE 22 OF THE MOTO Guzzi 1000 SPIII's OWNer's manual, you are cautioned to "Remember that components need several thousand kilometers before they are properly bedded-in; care taken in this period will ensure prolonged vehicle life.” Eric Phillippe, one of the co-owners of Moto America, Guzzi’s new U.S. distributor, puts it somewhat more succinctly: “Take it easy with this,” he advises in a slow, Southern drawl, “It’s about as tight as a tick on a dog’s butt. Takes maybe 5000 miles to really break-in a Guzzi.” We’re a long way from the shores of Lake Como and the village of Mandello del Lario, where Moto Guzzis have been bolted together for more than 70 years. We’re in Lillington. North Carolina, at the old Ford dealership on Main Street that now serves as the base of operations for Moto America. As reported exclusively in April’s Cycle World, Maserati Automobiles sold the U.S distribution rights for Moto Guzzis, and the existing stock of bikes and

No, YOU HAVEN'T STUMBLED ACROSS A RETROSPECtive article on a 15-year-old Italian bike. The Moto Guzzi 1000S before your eyes is a 1991 model, not a wonderfully restored classic, but even company spokesmen don't try to hide the Guzzi's lineage. "There's nothing new about this bike," says Moto America's President Fran Contaldi. Indeed, gazing at the gloss-black 1000S is like looking through a portal in time. The calendar flips back to the year 1974 to reveal Moto Guzzi’s 750S, a spitting image of the current 1000S, right down to the orange accent stripes. Look a little harder and you’ll see 197I’s V7 Sport, the machine that first let U.S. riders know Moto Guzzi could

spare parts, to Fran Contaldi and Mark Mecek. both former Moto Guzzi North America employees, and Eric and Emily Phillippe, who have run a Ducati/Guzzi dealership in Lillington for the past five years.

Moto America plans to pump new life into the Moto Guzzi name, a good thing, as the company has had a barely perceptible heartbeat for the past few years, selling just 200 bikes annually. Contaldi says that the company’s current. conservative business plan is based on selling that number for the next three years, with a jump, hopefully, to 500 units by the fourth year. “Possibly 1000, if things go really well,” he says. “There’s a viable market for Guzzi in America, even if a lot of things have gone wrong in the past. Even if the bikes are seen just as an obscure trend, we ought to be able to sell 500 a year.”

Selling some 200 non-current models, mainly Mille GT standards and California III cruisers is the first order of business. Later this year, the 1000S, and perhaps the 1000 SPIII sport-tourer, will go on sale, to be joined by the much-delayed Daytona 1000. the ohc. eight-valve sportbike based on the racer so successfully campaigned by builder Dr. John Wittner and rider Doug Brauneck (see “Killer Goose,” CW. February. 1990).

The fate of the SPIII is up in the air. Company officials aren’t sure the U.S. market will be receptive to a V-Twin sport-tourer that, at approximately $10,600, costs $1600 more than the class-leading Honda STI 100. After two days and 500 miles aboard the SPIII, we're not so sure about that assessment.

This bike has a lot going for it. For one thing, it’s mod> ern looking, with sweeping bodywork available in your choice of gray or a quite-trendy turquoise. Its detachable luggage, by Monokey, is spacious and literally a snap to get on and off. Its well-padded seat is comfortable, and its suspension, anchored by a fork with 40mm tubes (as opposed to the wimpy, 36mm unit used on last year’s Mille GT), does a good job—considering it’s no different in configuration than what Moto Guzzi has been using since the early 1970s.

build something other than a luxury tourer or a police bike.

The current incarnation may lack some of the more distinctive features of its ancestors, such as the 750’s swan-neck clip-ons—adjustable from a sporting crouch to a higher, touring stance—or its solo, race-style seat, which has been replaced by a more practical flat saddle. But, for the most part, the 1000S maintains the charm of its predecessors while benefitting from the use of more modern suspension components, brakes and tires.

Guzzi’s Bitubo fork and Koni rear shocks offer both spring-preload and rebound-damping adjustments, and deliver a reasonable ride, a good mix of sporting firmness and freeway compliance. Eighteen-inch Akront rims are fitted with Pirelli Phantom tires, which, while a technostep behind today’s frontline rubber, offer sufficient grip in both wet and dry road conditions. Steering is neutral and requires only a moderate amount of effort at semilegal speeds, more as triple-digit velocities are approached. The Italians claim a top speed of 145 mph for the S, though a good seat-of-the-pants estimate would be more like 120. In any event, straight-line stability is as good as any bike we’ve tested this year. The triple-disc, integrated braking system (the foot pedal activates the rear disc and one front disc, while the hand lever works the other front disc) takes some getting used to, but provides exellent performance and has a high threshold before wheel lockup.

It has been said that Guzzi’s 90-degree, longitudinalcrank V-Twin is somewhat agricultural in design, due to its simplicity and ease of maintenance; and, in fact, the first use of the engine was in a huge, slogging three-wheel utility vehicle employed by the Italian military. The present 949cc, air-cooled engine, with two pushrod-actuated valves per cylinder and a breaker-point ignition, is by no means the product of a frenzied development program. Rather, it represents the continued refinement of a design that has graced the Guzzi range since the mid Sixties. And. anachronism or not, the 1000S engine is an endearing old workhorse, with abundant reserves of torque. If so desired, you can lug around in fifth gear all day, though the engine

The engine also marks a departure for Moto Guzzi. Pre-

viously, there were two specifications for the 949cc VTwin, either a “big-valve” or a “small-valve” version. The SPIII splits the difference, its head having 44mm intake valves and 38mm exhaust valves, rather than the 47/ 40mm combination of the Le Mans-style motor or the 41/ 36mm set-up as used in the lower-performance Mille GT motor. The same philosophy applies to carb size: Where the Le Mans made do with 40mm mixers and the Mille had 30mm units, the SP is rigged with 36mm Dell’Orto pumpers. And. in a blow for modernity, the SP is the first Guzzi to be equipped with an electronic ignition.

To be honest, we couldn’t tell much difference between the SP's motor and the Le Mans-spec engine in the 1000S. Not that it mattered. Both engines are swimming in torque, and, while no speed demons, are two of the most user-friendly powerplants in the sport. We averaged 50 mpg on both bikes, despite the SP having slightly lower gearing than the S.

The not-so-good news about the 1000 SP is that its windshield delivers an infuriating blast of noisy, turbulent air to the faceshield of the rider. Also maddening are throttle-return springs so stiff that wrists are ready for a break after 50 miles of steady cruising. These two characteristics detract immensely from what would otherwise be a great machine for chasing horizons.

We’d like to see the SPIII get the improvements it needs. A simple shield reshaping and lighter throttle springs would triple this bike’s enjoyment level. With those changes, and a drop in price, the SPIII could find a home in America. E3

is happiest pulling from 5000 rpm up to the 8000-rpm redline.

The only serious complaint we have with the 1000S—as with other Guzzis fitted with Dell'Orto carburetors—is its absurdly hard-to-twist throttle. It feels as though you’re reeling in a 500-pound marlin, rather than yanking up a pair of measly throttle slides. A minor bother is the clunky gearchange action, which can lead to missed shifts unless the lever is toed with authority.

Those complaints aside, the 1000S is an easy motorcycle to like. Not a shred of pretension exists in this Guzzi, no promises of superbike performance or long-distance touring comfort. This is a straightforward motorcycle in the simplest form, one that works better than its 1970s looks might suggest. In many ways, the 1000S is the Italian equivalent of the Harley-Davidson Sportster—a minimalist motorcycle built around a hulking, charismatic VTwin—and to some people, it’ll be just as desirable a machine. There is one important exception, though: price.

At a current suggested retail cost of $9400—more than $3000 up on the XLH1200 Sportster, and $2400 more than last year’s $6995 Guzzi Mille GT—the 1000S is so overpriced that dealers should be issued ski masks and snub-nosed revolvers as part of their sales kits. The new U.S. importer is working at reducing prices throughout the lineup, and would like to retail the 1000S in the 7500dollar range. We wish the company luck in persuading the Italians to lower the price. The Moto Guzzi 1000S, quirky and antiquated though it may be, is a good bike, but it’s not $9400 worth of good. IS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSpeed Thrills

August 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeStatus Miles

August 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

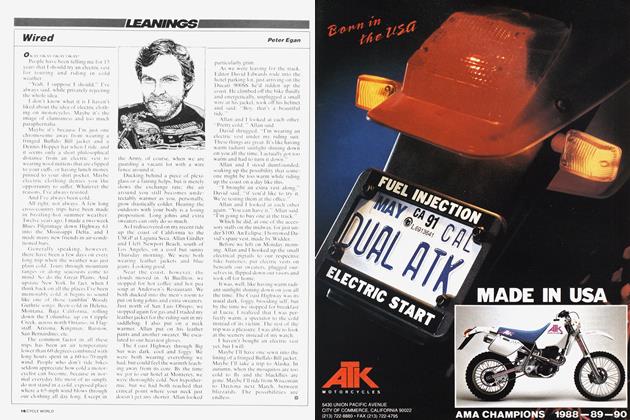

Leanings

LeaningsWired

August 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1991 -

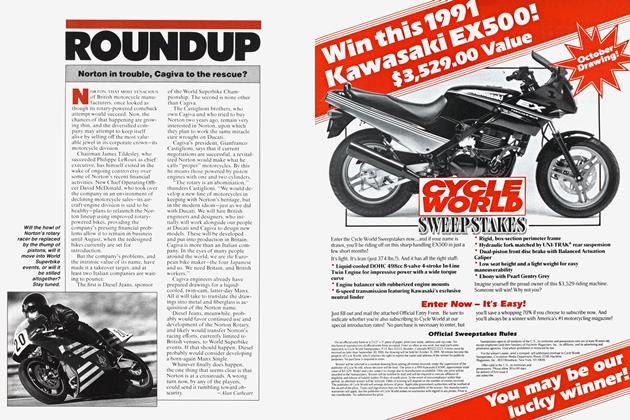

Roundup

RoundupNorton In Trouble, Cagiva To the Rescue?

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart -

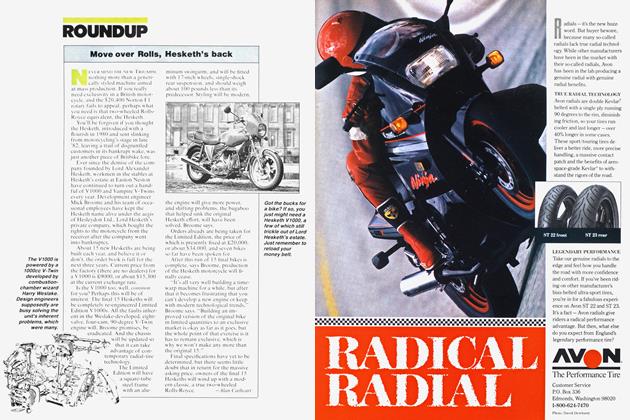

Roundup

RoundupMove Over Rolls, Hesketh's Back

August 1991 By Alan Cathcart