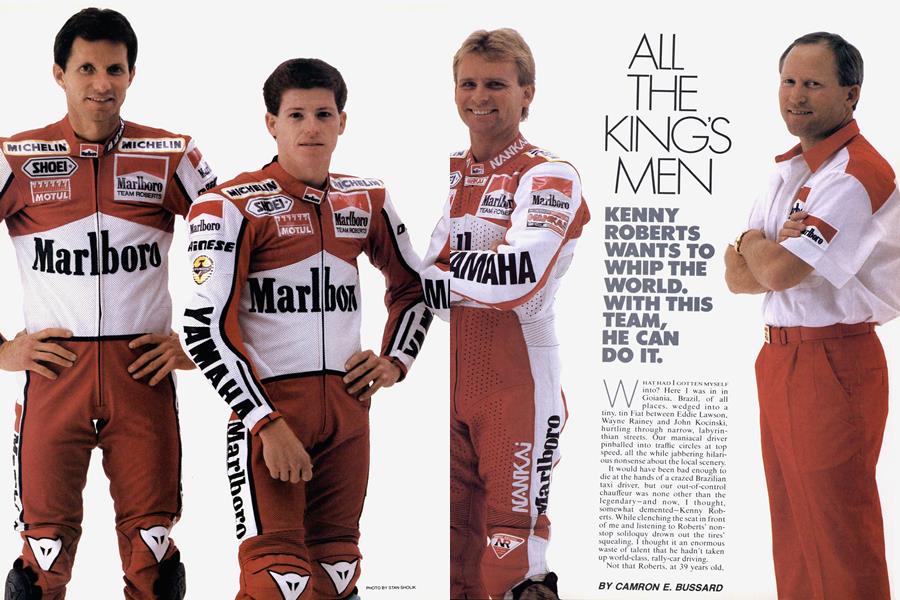

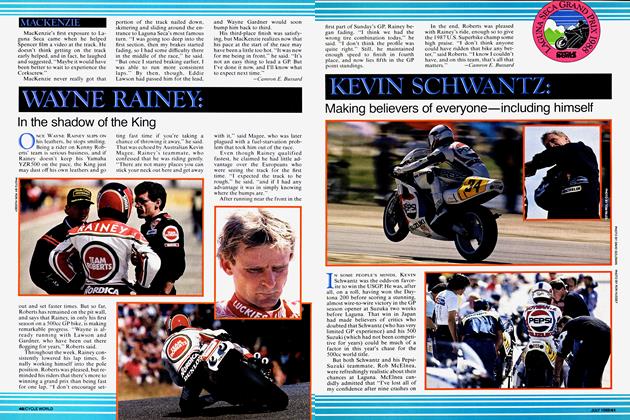

ALL THE KING'S MEN

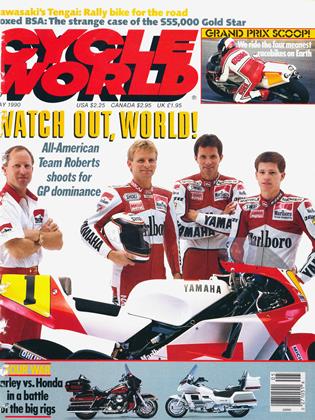

KENNY ROBERTS WANTS TO WHIP THE WORLD. WITH THIS TEAM, HE CAN DO IT.

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

WHAT HAD I GOTTEN MYSELF into? Here I was in in Goiania, Brazil, of all places, wedged into a tiny, tin Fiat between Eddie Lawson, Wayne Rainey and John Kocinski, hurtling through narrow, labyrinthian streets. Our maniacal driver pinballed into traffic circles at top speed, all the while jabbering hilarious nonsense about the local scenery.

It would have been bad enough to die at the hands of a crazed Brazilian taxi driver, but our out-of-control chauffeur was none other than the legendary — and now, I thought, somewhat demented-Kenny Roberts. While clenching the seat in front of me and listening to Roberts’ nonstop soliloquy drown out the tires’ squealing, I thought it an enormous waste of talent that he hadn't taken up world-class, rally-car driving.

Not that Roberts, at 39 years old, wouldn't welcome the opportunity, but his weekends for the next several summers are completely booked. As the owner/manager of Team Roberts, he doesn't get much time off'from a rigorous testing and racing schedule, and has traveled here to Brazil in mid-January for pre-season tire tests.

Since Roberts founded his ow n GP race team in 1 984. he has been sponsored by the Lucky Strike tobacco company, but that changed at the end of last season, when Roberts orchestrated the race-management coup of the decade. First, he persuaded Yamaha to provide his team with YZR50ÖS that would be a cut above the bikes supplied to other Yamaha-mounted teams. With that as a bargaining chip, he then signed fourtime world champion Eddie Lawson to a two-year contract to ride alongside established Team Roberts rider Wayne Rainev. who finished second to Lawson in the 1989 title chase. And with Lawson came Michelin-tire sponsorship. The French tire giant is generally acknowledged to produce the best roadracing slicks, and it was a slide-prone rear Dunlop that led to a late-season crash by Rainey in 1 989 that gave away his series point lead.

Finally, Roberts succeeded in abducting the 10-million-dollar Marlboro sponsorship from 1 3-time world champion Giacomo Agostini's team. Without top equipment and without a top rider. Agostini was unable to hold on to the Marlboro money. This changing of the guard is somewhat ironic, because in 1983, it was Roberts, in his last season as a racer, who persuaded Agostini, his team manager at the time, to sign Eddie Lawson as Roberts' co-rider. At the end of that year, Roberts left Agostini to form his own team, but Lawson stayed and subsequently won three w:orld championships for Agostini/Marlboro before leaving in 1989 to ride for Rothmans Honda, where he notched his fourth title.

Agostini will field a 250 team sponsored by Marlboro in 1990. but even there, he'll run up against Team Roberts/Marlboro, in the form of a young John Kocinski, regarded by many as the 250-class rider to beat, despite his scarce GP exposure.

The combination of Marlboro and Roberts along with Rainey, Lawson and Kocinski makes for the strongest team in current GP racing, and perhaps the strongest in GP history. 1 he prime goal for the team is have Lawson or Rainey win the 500cc title, but. in addition, Roberts wants his team to domineer, “to have both guys on the podium at each race." Marlboro’s budget, more than twice that of Lucky Strike's, should help the team meet both goals by allowing Team Roberts to do more testing and development, as well as to cover increasingly high rider salaries. Roberts refuses to reveal how much he pays his riders, but he does say. “1 think there are six riders making over a million bucks this year, and I have three of them.”

And Roberts is quick to defend those lofty earnings. Trackside at the test session in Brazil, he wears the classic Roberts squint-Dirty Harry mixed with just a touch of Howdy Doody-and points to Rainey, leaned over, sliding to the outside curb in a third-gear corner. “These guys put it on the line every time they get on a bike,” he says. “How much is that worth?” He also knows, as do the riders, that a slight miscue could swiftly snuff' out a career that doesn't last much past the age of 30 in any case.

With the experience his 50()cc riders have, it isn't necessary for Roberts to dote over them. He and Rainey have worked together for years, and of Lawson, Roberts simply says, “There is nothing 1 can teach Eddie. 1 can encourage him, and that will make a big difference.” This frees Roberts to concentrate on other matters, such as helping Kocinski, the three-time AMA Formula Two champion, adjust to his first season of racing full-time in Europe. “John is the best 250 rider in the world: nobody can beat him,” says Roberts. Others agree, comparing Kocinski to Freddie Spencer in the way he attacks a track, pushing his bike and tires beyond their limits, yet somehow maintaining control.

Roberts gives Kocinski a lot of attention. particularly w hen it comes to bike setup. But he has taken steps to make sure all of his riders constantly get the best information possible, which is why each machine is equipped with an on-board computer. “Our goal with the computers,” explains Roberts, “is to help get the bike as good as possible by Sunday.” To that end, the computers record such things as suspension travel, throttle openings and exhaust temperatures. With riders of Lawson’s and Rainey’s caliber, the computers usually confirm what is verbally relayed to the mechanics, but Roberts is hoping that the information will help speed up Kocinski’s learning curve.

Interpreting computerized data may prove to be an easier task than making certain everyone involved with the team gets to where he needs to be on schedule. Besides the core group of riders, mechanics, and technicians, consisting of 20 members, an additional 20 people or so converge on each race site from three continents and Japan. The numbers alone make day-to-day logistics a tribulation. and Roberts admits, “Sometimes just getting a meal can be a real problem.” With so many people involved. the potential for chaos hangs over the team like the sword of F)amodes. More than one top-flight GP team has been brought down by frequent internal squabbles.

To ease the tension, Roberts tries to remain out of the way during testing or practice, though he’s not above casual kidding around or even the occasional practical joke (in Brazil, a false set of buck-teeth, inserted just before he solemnly offered advice, was the running gag). Still, Roberts pays close attention to every alteration on a bike. “I don’t like to bark at people and tell them what to do,” he says. “If you do that all the time, people tend not to listen. I like to sit back and watch. If I see something that isn’t right. I’ll jump in.”

That’s illustrated at an open-practice day in Jerez, Spain, during the team's first test session with the 1990 bikes. The new 500s have arrived late, and the mechanics have scurried most of the night getting them ready. The riders are anxious to get on the bikes, but have to wait a few hours for 500cc practice to begin. The European press crushes around the pit area, and no one can leave without being accosted by two or three foreign journalists. As the test goes on, Roberts increasingly spends more time in the garage, listening to the riders and mechanics, suggesting changes to suspensions and brakes.

When he’s not involved in sorting out the new bikes, Roberts takes a back seat and attends to his other duties. In Spain, he will submit to 15 interviews. “Everybody has a job to do,” he says when asked if he gets tired of answering the same questions time after time. It’s not clear whether Roberts is talking about himself, the reporters or both.

It’s nearly impossible to think of modern GP racing without Roberts. Beginning in l 978. he conquered the Europeans on the track, shocking them with three consecutive world championships. But his devastating will to win wasn't the only weapon in Roberts’ continent-conquering arsenal. He wowed the Europeans off the track with a disarming good-ol’-boy smile, and there is no question he is still the top celebrity in the GP world and its most-influential figure.

Part of the reason for Roberts' popularity and influence is his sometimes-brutal honesty. He isn’t afraid to go into detail, for instance, on why he thinks U.S. riders have won nine out of the past 12 500cc championships, claiming, “European riders ride by how they feel. American riders ride by what they know.” He goes on to explain, in language too salty for publication, that European riders tend to be more emotional, more easily distracted by off-the-track events than are American riders. That’s why, Roberts thinks, it was so easy for him to “psych-out” his competitors when he was racing.

Roberts’ outspoken nature has also led to controversy, and his careerlong quest to make GP racing safer and more professional has often put him on the wrong side of sanctioning bodies and race organizers. Today, he worries that motorcycle racing's lack of media exposure in America will sway sponsors away from spending the huge sums of money needed to support first-class race teams.

“Only a couple of teams pay all their expenses with their sponsorship, and if those sponsors fail to get more return —meaning television — the sport may die because it's simply too expensive,” he says. According to Roberts, it takes a budget of approximately two million dollars just to run a one-rider team, half of that outlay going to lease a couple of works racebikes—full-on factory specials are no longer sold. Without increased television coverage in the lucrative and influential North American market, Roberts fears that fewer and fewer teams will be able to bag affluent sponsors, and the sport will be caught in a downward spiral.

If Roberts had his way, there would be competitive, low-cost engines available to any team interested, thus making racing more affordable. and he has made such a proposal to Yamaha. But for now, he will have to be content with the way things are.

And the way things are is pretty good for Kenny Roberts. He’s signed three of the best riders in the world to relatively long-term contracts. He has a proven team of mechanics and an organized support group, all of which puts him at the top of what could be the grand-prix dynasty of the 1990s.

Roberts no longer gets his adrenaline pumping by twisting the throttle of an ungodly fast racebike, but the desires that drove him to win two U.S. championships and three world championships still compel him to turn everything he does into a contest. And it doesn’t matter whether the challenge is guiding his team to a world championship, playing the best practical joke or thrashing a rental car through some backwater South American city.

He simply has to win.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue