The SECRET Springs

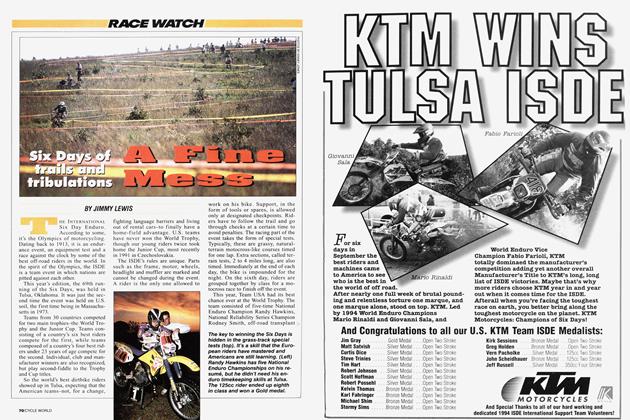

RACE WATCH

Speed in the streets, knobbies in the valley, trials bikes on the ski jump. But where is everyone?

STEVEN L. THOMPSON

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLOrado-It's Sunday, September 16th, and the sun has fallen below the aspen-covered hills above the Yampa River Valley. It's been another breathtakingly beautiful Rocky Mountains day, full of skies so blue you think they're computer-enhanced, and air so pure and clean an urbo-suburho motorcyclist's lungs grow younger with every breath.

The aspens turn color around here about mid-September, but that’s not why U.S. 40 starts sprouting motorcycle trailers in midweek. They come because the Timberline Trailriders, the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association, the Denverbased Motorcycle Racing Association and the local Chamber Resorts Association have combined to make Steamboat Springs, elevation 7000 or so and population 6000 or so, the center of some motorcycle magic unavailable anywhere else on Earth.

In a single week, here in Steamboat, you can ride a vintage trials. race in a vintage motocross, roadrace in a full day’s vintage events and then finish off with another full day’s modern roadracing. The icing on the cake is this: The scrambles is held on real dirt and grass, laid out by Dick “Bugsy" Mann, to replicate the oldstyle scrambles courses, and the roadracing all takes place on America’s only true street circuit.

This year's motorcycle week was the 10th annual MRÁ roadrace, the seventh annual AHRMA race day and the third annual vintage motocross. With such a long history, and with such tantalizing features, you'd think the town would be swamped by racers and fans and people just looking for an excuse to ride their Gold Wings through the most beautiful countryside in America. You'd be wrong.

According to Rob Stickler, local attorney, founding member of the Timberline Trailriders and mainspring of the event, there were maybe 2000 people in town for the whole thing this year. Counting the few hundred racers.

If the racing were lackluster, if the townspeople were surly and antirider, if the weather were awful, the scenery boring, the race organizations standoffish, maybe this would make some sense. But none of that is true.

As you wander around the race sites, savoring the stink of freshly burned castrol oil from the Rickman Métissés on the scrambles course, listening again to the lovely blare of the open meggas of the AJSs and Norton Manxes on the 2.2-mile, 1 1-turn street course laid out on the resort roads of the Mt. Werner ski village outside town, you see the nearly empty grandstands, the scattered few touring bikes, the VACANCY signs on the hostelries, and you realize there can be only one explanation: Somehow, the word just hasn't gotten out. To the world at large—even to the motorcycling world at large— Steamboat Springs is still a secret.

In a world of instant glitz and fame, this seems incredible. But it's true. Motorcyclists who will travel across the continent to experience Daytona or Loudon or Sturgis have let this one slip through their schedules. Sure, the timing of the thing is awkward—the second week of September is busy for almost everybody—and that’s a big reason, says Stickler, why the town and the resort association were willing to allow the motorcycle events to take place on the streets at all, 10 years ago.

There was little likelihood that closing the condo-lined streets on Mt. Werner would annoy many people, since so few people were in town then. Two weeks before the bike week is the vintage car weekend, which, in concert with the local airport’s fly-in, antique-airplane display and air show-, combines to completely fill Steamboat’s 15.000 beds and 70 restaurants. But two weeks later, the town is almost dead.

Thanks to Stickler, fellow' Timberliner and Team SCUM (it might mean “Serious Crazies Using Motorcycles." but then again, it might not) member Randy “Ewok" Osborne and the other Steamboaters with guts and vision, this dead zone was ceded to us in 1981. And some among us have savored it to the hilt. But something has stopped the word from getting out.

And get out it should. Dick Mann and the AHRMA/Timberline people each year lay out a 1.2-mile scrambles course that slams the nostalgia glands like Castrol R. There’s a class for everyone, it seems, not least because of Mann’s objective, which is, in his words. “First of all, to preserve, use and show the machines." The objective is more than met in the lush meadow at the base of Mt. Werner, only a few hundred yards below' the roadrace circuit. There, the roar of every conceivable kind of pre-1975 scrambler, from B35 BSA to twinpipe CZ and Earles-forked Greeves, reminds anyone who might need reminding of why and how we got to the almost-otherworldly MX machinery of today.

As you wander the pits placed in the huge paved parking lot only a dozen yards from the track, you sense that, at last, the knobby-tired community has found the same enthusiasm for classic racing that launched the classic roadracers a decade ago. Wisely recognizing that some of the enjoyment would evaporate for the older riders if they were forced to compete against teenagers racing vintage MXers. the AHRMA has not only a wide array of classes, but two age-based categories: Vets for riders over 30. and Old Timers for those over 40.

The result is not just that Dick Mann rides in one class and this year’s star visitor, ISDE rider Larry Roessler. rides in another: it’s what may be as near to the ideal combination of real racing, display, playingaround-with-numbers-on, and just plain fun that anybody’s come up with for bikes with knobbies. And not just on the scrambles course.

Across town a few miles, on Howelson Hill, site of the ski jump, the vintage trailers get their day in the sun. And like the course and rules governing the scrambles, the trials event is old-style. Adrian Moss, ace English champion w ho was beaten by Dennis Davis in the Modern Classic class, says that the insistence on rules once thought sacred in trails—such as the “no-stopping" rule, now no longer a part of FIM trials—keeps the competition “what it should be." In England, according to Moss, vintage trials now outdraws modern trials in numbers of spectators and competitors. Asked whether he thought the same thing would happen in America. w here the famous “trails boom" of 1974-75 never materialized, he smiles and says he can’t see any reason why not.

Behind his answer lies more than just personal affection for old bikes. In trials and scrambles, just as in roadracing, there are powerful factors luring old and young racers and wanna-be racers to old bikes—specifically, old British and European bikes. Aside from th ’'-worn notions of cultural and ^logical “comfort" that the* s and '60s Brit-

and Euro-bikes provide their American and European riders, there is economics: An investment in a classic competition bike, even a trials bike, is an actual investment, as many of the old crocks will hold their value or increase in price, even after a few seasons of hard, happy use.

As clear as this lure for riding old racebikes is in motocross, it’s unmistakable in the parking-lot pits for the vintage roadrace held the day after the scrambles. Like the MX pits, the roadrace paddock is full of the sights and sounds of yesterday; Team Obsolete is here with its all-conquering AJS 7R/Matchless G50 and gangly Dave “Rope” Roper to ride, as is Roper’s only real competition in the 350 event, Tom Marquardt and his ’62 Honda CB-77-based GP bike. Here too are prewar Nortons. Harleys and Indians, a potent and immaculate stable of Ducatis for Mike Green to ride (and win his classes with), as well as a CC Products-sponsored '72 BMW R75/5 for Eron Flory to duke it out with H-D XR750-mounted Pat Moroney in the 750 GP and Sportsman 750 class. And in between the exotic Nortons and ancient Harleys and neo-classic BM Ws are the staples of '60s club roadracing: Ducati Dianas, Bultaco Metrallas, even a beautiful Hodaka 100 GP racer.

A racer from that now long-ago era can walk the paddock at Steamboat, surrounded by the unmuffled blast of the past, and easily think himself transported to another time. Which is, surely, no bad thing. Certainly, as Team Obsolete’s outspoken leader, Rob Iannucci will tell you without too much provocation, there is much stress in the classic racing world, much agonizing about classes and courses and organizations and profit sharing and illegal modifications and bruised egos. But that’s true of any racing series, anywhere and anywhen.

At Steamboat, the issues lying just below the surface seemed to be the specifics of the interaction between MRA and AHRMA; about who ran what, for how much, and why. To those who, like Rob Stickler of the Timberliners, or Morrie Pape of MRA, or Iannucci of AHRMA, or Nick Rose of the Chamber Resorts Association, find themselves responsible for taking the idea of an event and turning it into organized, functioning reality, these issues are not trivial.

But beyond those issues—which are serious, and must be worked outlies the reality of Steamboat Springs itself, both as a competition venue and an experience. In both senses, it is unique, the roadrace track uncannily similar to the now-defunct Mt. Panorama track in Australia, and the dirt venues evocative of a time before techno-trick trials and stadiumcross. >

If the Steamboat Springs Motorcycle Week were only the sum of these three vintage/classic events, it would be a must-see for any motorcyclist, just as the surrounding countryside is a must-ride for any rider, from Winger to fire-roader. But the best part of the Steamboat experience is that you do not have to buy into any particular philosophy—from “Old is Best” to “FZRs Rule” —to enjoy it.

In mega-event terms, motorcycle sport has been essentially static in America for some time. Óur Meccas have remained more or less unchanged; Daytona. Sturgis, Laconia, Laguna Seca. Unadilla and so on. But times change, and so do events. So in Steamboat Springs, at the conclusion of 10 years of motorcycle sport, you can feel the change in the air. the gathering of previously unconnected trends and forces and people’s interests.

It is not just the aspens that are turning. At Steamboat, it’s suddenly clear that something new is happening in motorcycle sport, something born of classic-bike racing and of our new appreciation of the many pleasures of club racing and of America’s priceless, too-little-appreciated natural wonders. >

No more than anyone else does, you don't know what this new thing is, or might be. But there are clues. You hear, for instance, as you walk away from the last awards ceremony, talk of next year's innovation for “The Springs," which might well be holding a vintage flat-track event at the under-utilized fairground dirt oval. And which might well draw more than 1 50 veteran flat-track racers, stars and could-have-beens.

You hear of ever closer cooperation and coordination between the four associations that have brought th is unique piece of Americana to life. You hear those w ho labor hard and long to make it happen decide that their own psychic payback in pulling it off gets higher each year, as more and more people “discover" the race and the place.

And you see, in the smiles of the spectators who have savored in a single four-day span the sound of the past and the fury of the future, something beyond the obvious. You see the first faint signs that someday we might all say, “Steamboat” in the same way we now say, “Daytona".

It's a startling vision, to be sure. But visions come easily up here. They don't call it a Rocky Mountain High for nothing. Is3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue