Fathers, sons and motorcycles

UP FRONT

David Edwards

THE OWNER OF THE NAUTICAL-NICKnack shop was most kind. When she saw my friend and I walk in after parking the BSA, she offered to store our helmets and jackets behind the counter. “I’ll bet you can tell me.” she said with a sudden air of seriousness, “what all those people were doing at that motorcycle shop on Pacific Avenue. There must have been 200 motorcycles there. It looked very intimidating.” Rather than launch into my lecture on the evils of stereotyping, I told her that what she had seen couldn't have been more innocent, that it was just an annual Father's Day celebration.

Century Motorcycles in San Pedro has been in its present downtown location for about 40 years. A purveyor of BSAs and Triumphs before taking on Kawasakis, the shop is today one of the lynchpins in Southern California’s classic-bike scene, with a showroom stocked with the relics of a time when British Singles and Twins ruled the highways and backroads of America. Every Christmas and every Father’s Day for the past 12 years, Century’s owner, Cindy Rutherford, has thrown a Sunday-afternoon party complete with free food and punch. This Father’s Day, some 1000 people attended, sharing stories and gazing at the hundreds of old motorcycles that lined the curbs around the shop.

More than a way of saying thanks to her many customers, Cindy’s Father’s Day bash honors the man who started Century Motorcycles, her father, Bill Cottom. Bill is 83 years old, hard of hearing and short of teeth, but his wit remains intact. Last Christmas, I asked him about the price of one of the several Vincents that stood, roped-off. among the other bikes on the showroom floor. “I’m not sellin’, I'm buyin',” Bill shot back, before detailing all the Vincents he'd let slip through his hands over the years.

As the BSA thumped away from San Pedro, my friend's pockets jingling with seashells, I reflected on the importance of fathers to motorcycling. Certainly, they can pave the way for a son (or daughter) to enter the sport, or throw up any number of roadblocks.

My dad was a pretty good paver, having been a motorcyclist before he was a father. I've got a sepia-toned snapshot of him at 22, proudly astride his new 650 Triumph Thunderbird. a bike he scrimped and saved for two years to buy. He and my future mother courted on the Triumph, which was then sold so they'd have enough money to get married. With the next seven years came a secondhand Ford, a house, two sons and then a move from England to America, though no replacement for that blue-gray Thunderbird 650.

But motorcycles remained an interest. Weekend family outings included visits to museums, amusement parks, beaches, battlegrounds and the occasional bike race, usually a rough scrambles held in a local farmer’s field. And when my brother and I wanted to do more than watch, my father helped us rebuild a $10 mini-bike that had caught fire and almost burned down the neighbor’s carport that held it. Riding lessons in a vacant lot came next, and when we'd thoroughly explored the performance envelope of that lawn-mowerengined machine, a Yamaha Enduro 90 followed, its price drastically reduced when the previous owner didn't quite make it to the other side of a drainage ditch.

After he grafted a new front end onto the Yamaha, my father then initiated us into the ways of clutch work and gear shifting, something at which I proved amazingly inept. After what seemed like an hour of graceless stalls, he climbed on behind me, placed his hands over mine, worked the controls, and away we went, smooth as glass, me all smiles, he no doubt wondering how a son of his could be such a klutz.

A few years later, he and my mother loaned me the money to buy my first streetbike. a used $400 Honda CB175. When I sold that sweetheart and traded up to the world's most-breakdown-prone CB350. he used the numerous patch-ups to teach me the importance of proper maintenance, and the inevitable engine rebuild to explain the complexities of internal combustion. “If a job is worth doing, it's worth doing right,” he'd sagely remark as he extracted nuts that I'd just rounded-ofT or synchronized carburetors that I'd dutifully spent 30 minutes messing up. He was also able to somehow fix flat tires in minutes without bloodying a knuckle of pinching an inner tube, a feat I ranked second only to that of landing a man on the moon.

In 1985, well into my journalistic career, I rode Cycle Worlds test Honda Gold Wing SE-i back to Texas for Christmas. The morning after my arrival, my dad had the bike hosed down and was attacking it with a bucket of suds, getting rid of 1500 miles' worth of road grime. By the time I’d gotten out of bed. he’d already checked all the fluid levels and was scouring the owner’s manual, familiarizing himself with the Honda's various gizmos and gadgets. I forget what I got him as a present that holiday; whatever it was paled when compared to fun he had riding around on that Gold Wing.

When my parents came out to California the next summer on vacation, they borrowed the Wing—then in the midst of a 27,000-mile longterm evaluation—and rode up the Pacific Coast Highway to a rally in San Francisco. My father came back from the trip even more in love with the Gold Wing, asking if he could buy it from Honda when the magazine was through testing it. I told him I'd make the arrangements.

But my father never got his Gold Wing. Six weeks later, 57 years old, he was dead of a heart attack.

George Herbert, an English writer, is probably best known for proclaiming that “Living well is the best revenge,” but I favor his “One father is more than a hundred schoolmasters.”

Thanks for the lessons, Dad. ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeOut In the Midday Sun

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Discriminating Cheapskate

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersDinin' Dressers

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupConquest Goes Polish

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

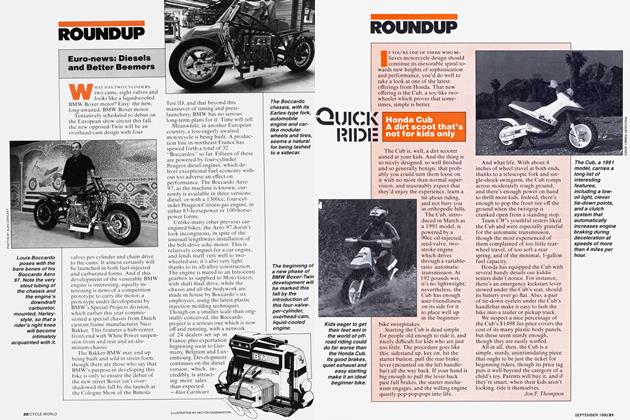

Euro-News: Diesels And Better Beemers

SEPTEMBER 1990 -

Roundup

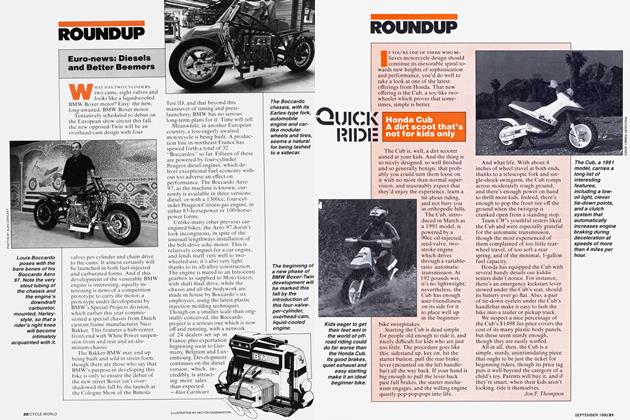

RoundupHonda Cub A Dirt Scoot That's Not For Kids Only

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Jon F. Thompson