AT LARGE

Bike roads

Steven L. Thompson

THE CENTRAL VALLEY OF CALIFORnia is about as close as the state comes to being Kansas. It's mostly pancake-flat, rivaling the black-dirt Midwest states in agricultural production, and beating all of them combined in bug production. Since I spent my high-school years near enough to the Central Valley to have to cross it to get to the mountains or the sea, I became all too familiar with the valley. I also came to loathe it. Its arrow-straight two-lanes bordering vast orchards or farms were the antithesis of the roads I was seeking out as a new rider-the roller-coaster mountain twisties and the interlinked coastal horseshoes. Those, not the boring valley alleys, were real "bike roads."

Or so I thought. It took 20 years for me to think otherwise. Twenty years of planning all my motorcycle trips to avoid any road straighter than a French curve, of avoiding all interstates if possible, and of imagining that the fun of motorcycling would inevitably be corrupted by too many straights.

This aversion to straight roads is familiar to all enthusiasts, whether addicted to two wheels or four. When I considered that aversion recently, all the usual arguments against the interstate as a bike road came pouring out of a well-worn mental file folder. Too many trucks. Too many cops with nothing to do but aim radar guns. Too much similarity, sea to sea and border to border. Boring roadhouses. Boring roadfood. Just plain boring.

Well, maybe. But maybe not. I'm beginning to think we don’t really understand our own interstates these days. I’m beginning to think they’re a lot more interesting than they used to be, back when the huge building programs begun by Ike rammed them across the open spaces. Back then, there was a lot of truth in the charge that you could drive from coast to coast on, say, 1-80, with little sense of what kind of America or Americans lay behind the next off-ramp. But a lot of the wide open spaces aren't wide or open any more, and the interstates have begun to take on distinct local characteristics, much as the thruways and freeways of most of our big cities each have their own quirks that give them a peculiar kind of personality. These changes are evident in a car. but especially so on a bike.

Consider the interstates that span the great Southwest. It’s taken more than a few crossings of the immense red deserts for me to realize how much more fun it is to do it on a bike than in even the best car. When I drove my Jaguar XJ6 across the frying pan, it was just a trip. But when I did it on a Harley FLH or a Kawasaki Six. it was a different experience entirely. I saw things that were invisible from the Jag. I sweated. I smelled the subtle changes in the biomes — changes I never even noticed in the air-conditioned cocoon of the car.

Self-styled sport-touring types, as well as hard-core pure sport riders, often scoff at those who ride a lot on the interstates. “Why don't they just get a car?” is the most-oftenasked rhetorical question among these guys, who assume that their own decisions about what constitutes a real bike road must apply to everyone. And for years, I shared some of their disdain for putting a vehicle manifestly so happy when leaned over, into an environment where it leaned seriously only twice: once at the onramp and again at the off-ramp.

But for whatever reasons, the interstates are no longer really homogenized. In my trip around America last summer, I was startled to see how regional they’ve become; how the stubborn. proud sub-cultures of America have stamped themselves on the supposedly uniform concrete rivers of our national commerce. People in the media and academia have been telling each other for so long that America is becoming one vast plain-vanilla culture that they obviously believe it. But if you abandon prejudice and hit the big roads to find out, you discover a different reality from their tidy abstractions. When you’re in Dixie, even on a superslab, you know you're in Dixie. And the same goes for Down East and the Northwest and the Great Plains. For everywhere.

The awful truth behind some of these revelations for me is that it isn’t just the aging of the roadways that makes me interested in interstates; it’s my own aging as well. Once I was content to think of a motorcycle ride mostly as an excuse to stimulate the kinestheal gland (unknown to medical science but found in all motorcyclists, pilots and roller-coaster junkies). Age has inevitably changed that. Now a motorcycle ride is many more things for me. I still enjoy having the old K-gland give the system a buzz when it dumps the K-hormones at the first glimpse of a sign that reads, HILLS, CURVES NEXT 200 MILES, but I also find new interest in places and people where the road is flat.

When you comprehend this, it helps you to understand—if you’re a hard-boiled sport rider—why Mom and Pop like to roll across the country on their Gold Wing. Maybe you’ve always thought it was because they were afraid of leaning the thing over. I don’t know about that; everyone’s tilt-o-meter is calibrated differently. What I do know is that the answer to “Why don't they just get a car?” is this; Because, even on the straightand-level. they’re getting something very special out of their motorcycle ride.

I discovered how special what they get is recently, when I took a long, lazy ride across the Central Valley that I once so despised. The bugs were just as bad, the road just as flat. But the ride was fascinating; in its own way as delightful as any I’ve done, from the Alps to the Alaska Highway to the Blue Mountains of Australia. I came away with a new understanding of the valley and its people and places. But best of all, I came away from the ride with this realization; Ultimately, all roads are bike roads. And you don't need the right bike to enjoy them. Just the right attitude.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

April 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

April 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupMichelin Pulls Out of U.S. Bike-Tire Market

April 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

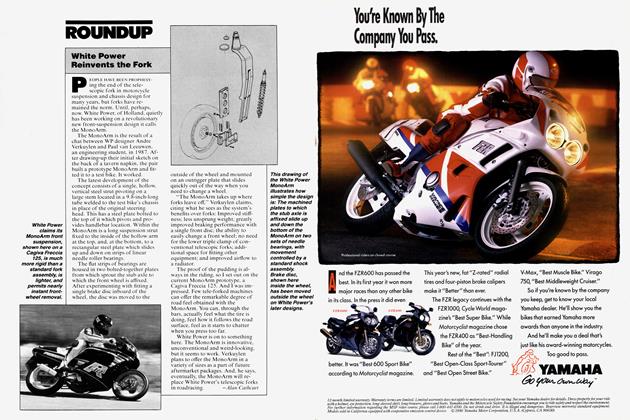

RoundupWhite Power Reinvents the Fork

April 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

April 1990 By Alan Cathcart