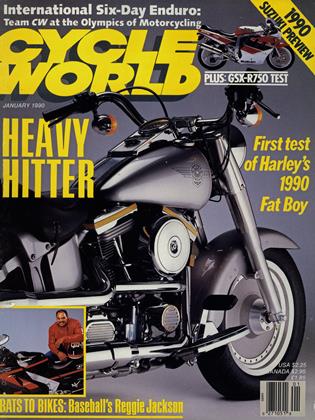

Once and future Harleys

AT LARGE

Steven L. Thompson

WHAT’S THIS? A FEW SCORE CELEBRIties have decided that nose candy is Out and Harleys are In? Harley dealers must be smiling. Not because of the publicity, but because the celebs aren’t leading the trend, they’re following it.

The gurus in our game have lavished a lot of word-energy on this, the New-Age Harley Phenomenon, trying to see what it really means. Some of the resulting blather about style and hipness and highway cowboys and so on even makes some sense. But you don’t have to be a sociologist to understand why somebody would like riding a Harley. You only have to be a motorcyclist.

Harleys are fun. Period. Not only that, in a motorcycle era characterized by highly focused technology, they’re comfortably fuzzy. Get on a sportbike and you’re immediately challenged by the thing: Perform right, the bike seems to be saying to you, or get off, bozo.

Harleys challenge nothing but your prejudices, and, in some Hardtail cases, your butt-endurance. Climb on any Harley-Davidson and right away the world slows down. Nobody expects you to carve the right lines. Nobody expects you to do much except rumble along.

As much as any aspect of the renaissance of Harley-Davidson, it’s that last one that is the most interesting to me. There was a time, not so long ago, when people did expect something from Harley riders. A lot of folks expected anybody on a Hog to be looking for trouble. Not any more. Now that you can buy the Devil-Biker-from-Hell look at your local department store, it may be time to bid the Devil Biker himself goodbye, at least as a major bad-guy image in our society. How, after all, can a self-respecting Devil Biker hope to terrorize the locals by his appearance alone when the locals begin to look like him, and even ride like him? One answer—and a sobering one—would be that the truly deranged will be forced to get even more psychopathic, but maybe not. Maybe the long reign of the Wild One is clanking to a halt, victim of its own badness and the new Harleys’ mechanical goodness.

From a practical standpoint, what might be happening in the gang world doesn’t seem to matter anywhere else. America at large has lustily embraced the Hog and all its trappings. If you miss this in daily life, where the signals are scattered on the road, you see it in clear relief at Ascot Raceway in Gardena, California.

There are a few places on Earth where you can see everything and everybody, if you wait long enough. Ascot’s one of those places. Just as the Ascot in England is as much a parade ground of style as it is a racetrack, so is the Ascot in Los Angeles. People come not simply to watch the races, but to watch each other. In Harleyland, just as in horse-land, style is everything.

And everything, at Ascot Raceway, is Harley-style. I note this again on a September Saturday as I settle onto the hard wooden benches for the AMA National Half-Mile. Hogwild people are everywhere. Does it irk the gent next to me, whose shifterworn engineer boots, twistgrip-darkened hands, air-blasted bloodshot eyes and bug-spattered leather vest so clearly identify him as a “real” Harley guy, that just in front of us sits a whole row of white-collar types outfitted in the best “colors” their money can buy in Beverly Hills? Not so you’d notice.

Maybe the roadworn fellow next to me who follows Chris Carr’s lines so intently does not think, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” but it’s true nonetheless. And maybe those gaily chattering fortyand thirtysomethings just in front of us are not themselves consciously emulating everything the “real” Hogmaster stands for.

At the root of all this, it seems to me, is the motorcycle itself. If most of today’s Harleys were not what they are-mostly safe, pleasant rides— then the Harley-style fad would be just that. But Harley dealers aren’t smiling all over America because department stores sell phony “colors” as easily as they do phony bomber jackets. It’s all because the bikes are, ironically and paradoxically, increasingly the least threatening of the motorcycles on the market today.

Consider that 20 years ago a Sportster was a “big” machine, a road rocket often paired in comparisons with the Triumph Bonneville. Then consider how small, how relatively simple and tidy a Sportster looks now. Milwaukee Iron? Sure. But it doesn’t gross anything like a Gold Wing Aspencade. Our mental calibrations of “big” and “fast” have been reset. And machinery that once seemed complex and gargantuan now seems almost friendly.

I noticed this first among my riding friends who are a little older than my 41 years. One guy in particular encapsulated the back-to-Milwaukee phenomenon. He’d been a championship racecar driver, is still a racing pilot, and has ridden everything from a Honda NS400 to a Kawasaki 1000 Concours. Last I’d seem him, he was on the Concours. Then he showed up on his new Softail, grinning likewell, like a happy motorcyclist. He’d followed the age-old rule of seeking the best in life, he said: Keep It Simple, Stupid.

There are a lot worse philosophies than that, and a lot worse motorcycles to find it in than a Harley. But the best part of all this Harley furor is this: It’s drawing new people to the sport. Some, undoubtedly, will shift away with the shifting fads, just as many of the celebs will inevitably find new means to gain publicity. But some will stay with us, having discovered that, while a Harley won’t take you to heaven, it will take you somewhere you’ve never been before, even if you ride the same places you drove your car.

When you look for the magic in a Harley, after all, look not at its name, but its game: It’s a motorcycle, first, last and always.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSocial Security

January 1990 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsHigh Finance

January 1990 By Peter Egan -

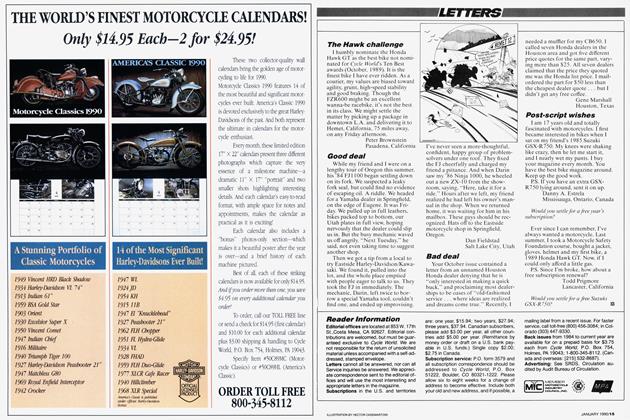

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupSwiss Citybike: Motorcycles Become Electric

January 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupStarts of the Tokyo Motor Show

January 1990 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupQuick Ride

January 1990 By Alan Cathcart