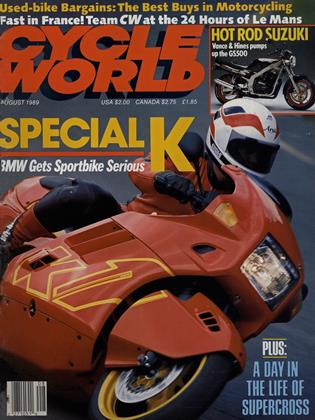

24 Heures du Mans

RACE WATCH

A roadrace, from the people who brought you the Foreign Legion and escargot

DOUG TOLAND

AS I BOUNCED AND SLID ALONG the asphalt on my back, I had only one thing on my mind: survival.

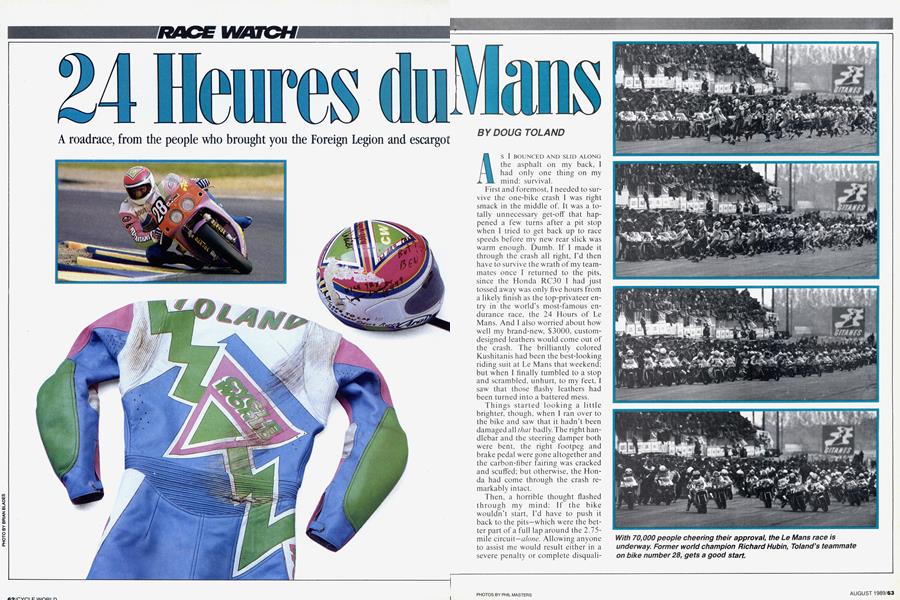

First and foremost, I needed to survive the one-bike crash I was right smack in the middle of. It was a totally unnecessary get-off that happened a few turns after a pit stop when I tried to get back up to race speeds before my new rear slick was warm enough. Dumb. If I made it through the crash all right, I'd then have to survive the wrath of my teammates once I returned to the pits, since the Honda RC30 I had just tossed away was only five hours from a likely finish as the top-privateer entry in the world’s most-famous endurance race, the 24 Hours of Le Mans. And I also worried about how well my brand-new, $3000, customdesigned leathers would come out of the crash. The brilliantly colored Kushitanis had been the best-looking riding suit at Le Mans that weekend; but when I finally tumbled to a stop and scrambled, unhurt, to my feet, I saw that those flashy leathers had been turned into a battered mess.

Things started looking a little brighter, though, when I ran over to the bike and saw that it hadn’t been damaged all that badly. The right handlebar and the steering damper both were bent, the right footpeg and brake pedal were gone altogether and the carbon-fiber fairing was cracked and scuffed; but otherwise, the Honda had come through the crash remarkably intact.

Then, a horrible thought flashed through my mind: If the bike wouldn’t start. I’d have to push it back to the pits—which were the better part of a full lap around the 2.75mile circuit—alone. Allowing anyone to assist me would result either in a severe penalty or complete disqualification. But God must have been looking down on me, because when I punched the starter button, the VFour engine miraculously roared to life as though the crash had never happened.

A few minutes later, I had the RC30 back in the pits, where the Team Arom crew converged on it like a swarm of killer bees. No accusing fingers were pointed in my direction; instead everyone pitched in to change all the broken parts, patch the fairing and even install a new set of tires and fresh brake pads all around. Before I knew it, I was back on the track and trying to make up the 30 minutes our team had lost because of my fall.

That pit stop involved some impressively fast repair work, I thought to myself as I carefully worked back up to speed on the track. But then, the three-bike Team Arom operation consists of some pretty impressive people. Based in Canada, the team is managed by Didier Constant, whose primary occupation is as Managing Editor for the Canadian motorcycle magazine Cvcle 1. The bikes are put together in France, however, under supervision of the team’s crew chief, Hervé Bazin, a man who has been preparing endurance bikes for more than a decade. He is assisted by what seems like a legion of mechanics, all of whom seem to have intimate knowledge of the RC30’s workings.

Just in case you think this operation is anything but first-class, you should know that the team even travels with its own doctor and a cook— Jean-Phillipe, who prepared superb breakfasts, lunches and dinners for the entire 38-member crew. And our effort wouldn’t have run nearly so smoothly without the wives and girlfriends of the various team members. They worked the pit boards throughout the entire race, and used hair dryers to warm boots, leathers, gloves and helmets before the riders would go out on the track for their 50minute stints in the 45-degree weather that prevailed in northwestern France that weekend.

Of the team’s three RC30s, two were ridden by three Canadian riders each, while I shared the third (which was actually considered the team’s Number One bike) with a Canadian and a Belgian. Our bike’s lead rider was Richard Hubin, a 33-year-old former endurance world champion from Belgium who has had factory rides with all four of the Japanese companies. Hubin has competed in the 24 Hours of Le Mans for the last 10 years, finishing no worse than fourth and suffering only two DNFs. Our Canadian rider was Jacques Guenette, Jr., a 19-year-old exmotocrosser in only his second year of roadracing, competing in his firstever endurance race. If his future is anything like his first year of racing, Guenette probably will win a pile of races before it’s all over.

I was invited to be part of the team mostly because of my endurance racing experience here in the U.S. I was the lead rider on the Suzuki-sponsored Team Hammer bike that won the 1986 National Endurance Championship. And after reading about Team Cycle Worlcf s strong showing in last year’s 24 Hours of Willow Springs (see “Night and Day,” CW, December, 1988), Arom Team Manager Constant thought I would be an ideal North American addition to his operation.

I have to admit, though, that despite all my racing experience, plus about five years of test riding with Cycle World, I had never thrown a leg over an RC30 before Le Mans. That’s not surprising, since the RC30 is a non-U.S. model that few Americans have ever seen in person, let alone raced. But it didn’t take me long to get comfortable with the machine—or develop a healthy respect for its racing potential. Physically, the bike seems rather small, feeling more like a 500 or 600 than a 750, but in terms of power, it feels more like a 1000. Roll the throttle open on this bike at any rpm, and it yanks your arms straight and accelerates hard all the way to its 13,000-rpm redline.

Admittedly, our RC30 was not stock. It had been fitted, among other things, with HRC (Honda Racing Corporation) cylinder heads, an aftermarket 4-into-l exhaust and Dunlop radial slicks. This combination worked well enough to keep us running in the top 10 throughout most of the race.

But doing so was no easy feat. For one thing, many of the bikes that compete in this race are exotic, hand-> built factory prototypes that are worth small fortunes. Not only that, but at Le Mans, unlike most endurance race held in the United States, teams must first qualify before they are eligible to race. That makes for much closer competition—as evidenced by the fact that our Number One Team Arom bike managed to qualify only 12th out of 65 entries.

Still, I was elated just to be in the race. And my elation turned to sheer, almost-tearful pride just before the start of the race when the national anthem of each competing rider’s country was played—including the U.S. national anthem. Since there were no other Americans in the field, “The Star-Spangled Banner’’ was played for just one person: Me, described by the track announcer as “LAméricaine Dooglas Tulaand. ” I can’t even begin to describe to you how I felt while that familiar song was playing, but I can tell you this: I’ll never forget it as long as I live.

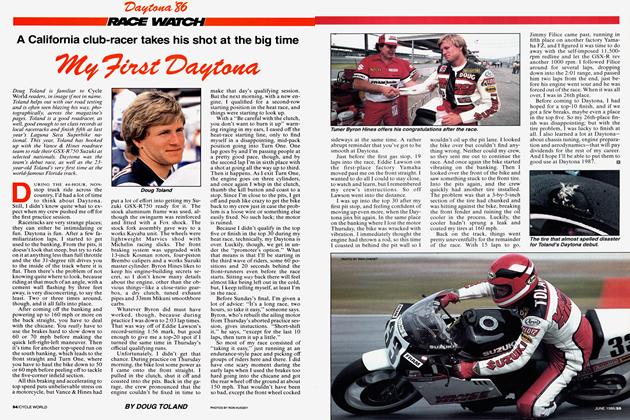

The start of the race was pretty memorable, too. As the 3 p.m. start time drew near, the stands along the front straight began to fill with people until every available inch was taken. In U.S. endurance racing, riders and pit crews usually outnumber spectators, but in France, 70,000 fervent race fans watched intently as each team’s lead rider took his place across the track from the bikes in readiness for the —what else —Le Mans-style start.

When the flag dropped, 55 booted pairs of feet scurried towards the motorcycles, waiting with dead engines 60 feet away. Reaching the bikes, each rider swung into his seat before launching his machine into the screaming, jostling fray of racebikes. Hubin did a good job with our RC30 and as the field blasted away for the first lap, we were in the top 15.

The excitement of the start out of the way, the race then settled into what all 24-hour endurance races become: a long, tough grind. Like a war, endurance races are played out in strategies. Ours was simple: Go reasonably fast and try to stay out of trouble. We knew there was little chance of staying with the five fastest qualifiers, a pair of factory-supported Honda RVFs, basically ultralight, ultra-fast RC30s; two factorysupported Kawasaki ZXR-7s, basically ultra-light, ultra-fast ZX-7s;> and a lone, factory-supported GSXR750R-model, basically an ultralight . . . well, you get the picture. Still, we knew our team was capable of a top-10 finish; with luck, even higher.

As day turned to night, our luck held, and by 10 p.m., we were in seventh place overall. The experienced Hubin, one of the smoothest, mostpoised riders I’ve ever seen, set a good example for Guenette and me, riding the RC30 to its limits but never once putting a wheel wrong. And for me, the night-riding stints in France were not as challenging as what I’m used to in the States: Unlike U.S. endurance tracks, where only a hundred yards or so of track are lighted for scoring purposes, Le Mans’ Bugatti circuit (only cars use the long course with its famous, three-mile-long Mulsanne straightaway) had lights in nearly every corner.

More of a problem than any darkness, though, was campfire smoke wisping across the track from various tent sites around the course. Faced with such opaque clouds, our bike’s piercing, $500-a-pair headlights were almost useless.

But the lights did come in handy for illuminating oil on the track, left there by blown engines or as the aftereffects of case-grinding crashes— and there were plenty of mechanical failures and crashes. Of the 55 bikes that started Le Mans, more than half weren’t around for the finish, including the other two Team Arom RC30s. The factory-backed Suzuki team, last year’s world endurance champion, was forced out with mechanical woes, and even the mighty HRC Honda France team had troubles. Their Number One bike, piloted by English rider Roger Burnett and two Frenchmen, Alex Vieira and Jean-Michel Mattioli, would go on to win the race by almost 10 laps, but not until Burnett—who had broken bones in both feet two weeks before the race—was forced to painfully push the bike for a half-mile after the drive chain broke. The other HRC bike, ridden by Australian Mel Campbell and Miguel and Mario DuHamel, sons of Canadian roadrace star Yvon, was in contention for the lead until two crashes dropped it to an eventual fourth place. The two works ZXR entries took advantage of the situation, with the Kawasaki France bike finishing second overall and the Kawasaki Japan bike tucked into third.

And we had a good chance of being in fifth place, until my leathersscraping, helmet-grinding, RC30wrecking mistake in the 20th hour while we were in sixth place and closing. By the time the rabid French fans stormed over the fences and onto to the track, forcing the race to a stop eight minutes before its 24 hours were up, we had climbed back to seventh place: Not fifth, as we almost surely would have gotten, but not bad, either, in the world’s premier endurance event, riding against the most-professionally run teams I had ever seen:

Back at the Team Arom tent in the pits a celebration had begun. Joining in, I was presented with my crashdamaged helmet, autographed by the team members, and then the cook broke out bottles of champagne, loaves of French bread and mounds of pâte. We shook hands, toasted each other and drank to success at the next French 24-hour race, the Bol d’Or in September. Before saying goodbye, Didier Constant asked if I’d like to be part of the Bol d’Or effort.

After getting a good night’s sleep, I started checking airline schedules. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupNew, Top-Secret Triumph Revealed

August 1989 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupFor Japan Only: the High-Tech 250s

August 1989 By David Edwards