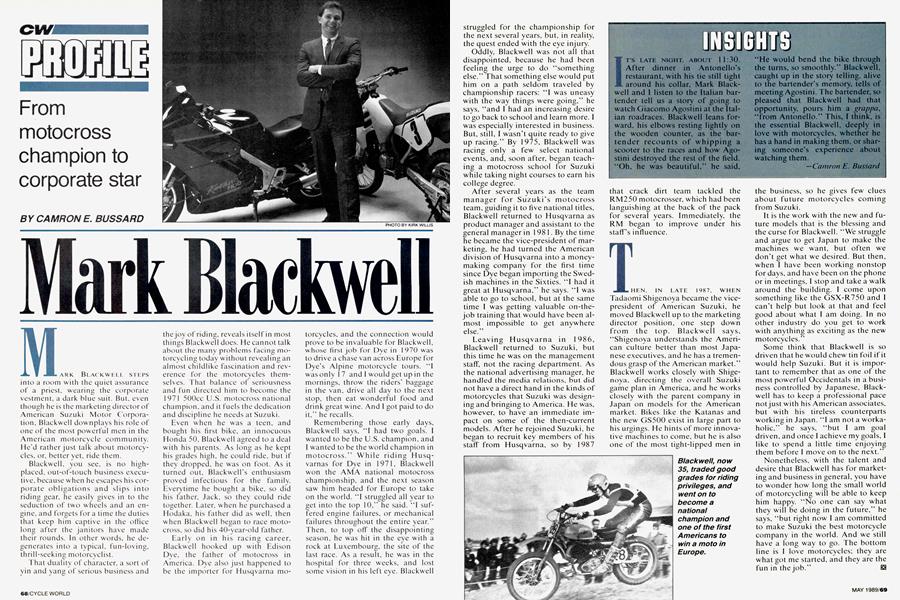

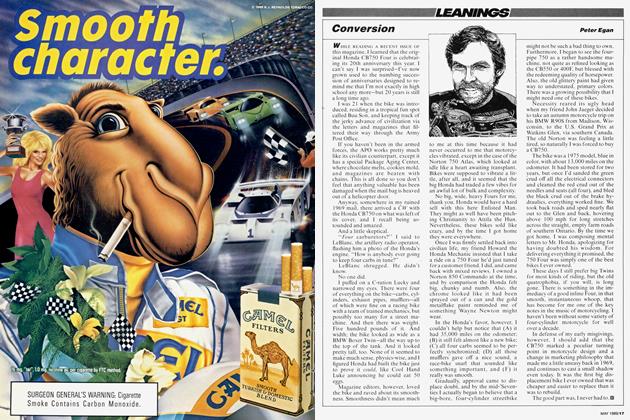

Mark Blackwell

CW PROFILE

From motocross champion to corporate star

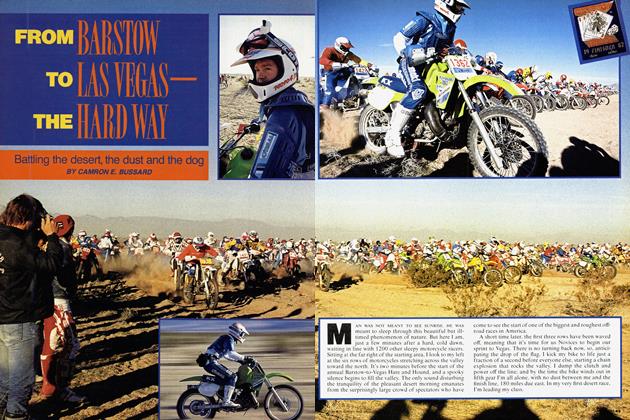

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

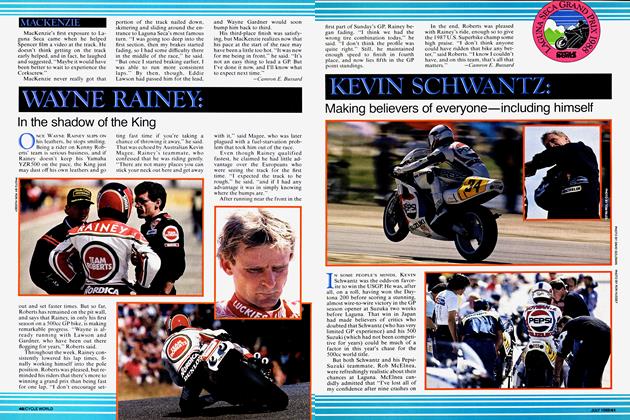

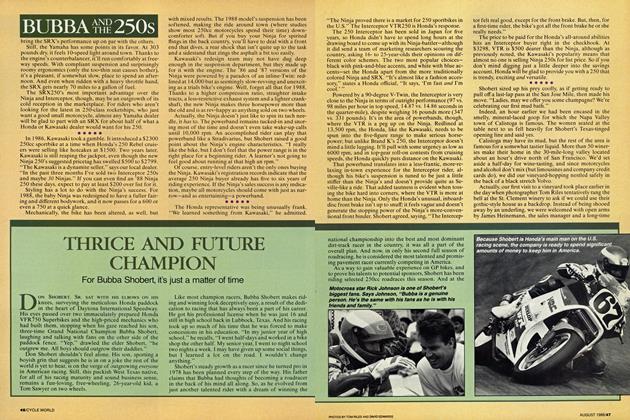

MARK BLACKWELL STEPS into a room with the quiet assurance of a priest, wearing the corporate vestment, a dark blue suit. But, even though he is the marketing director of American Suzuki Motor Corporation, Blackwell downplays his role of one of the most powerful men in the American motorcycle community. He'd rather just talk about motorcycles, or, better yet, ride them.

Blackwell, you see, is no highplaced, out-of-touch business executive, because when he escapes his corporate obligations and slips into riding gear, he easily gives in to the seduction of two wheels and an engine. and forgets for a time the duties that keep him captive in the office long after the janitors have made their rounds. In other words, he degenerates into a typical, fun-loving, thrill-seeking motorcyclist.

That duality of character, a sort of yin and yang of serious business and the joy of riding, reveals itself in most things Blackwell does. He cannot talk about the many problems facing motorcycling today without revealing an almost childlike fascination and reverence for the motorcycles themselves. That balance of seriousness and fun directed him to become the 1971 50()cc U.S. motocross national champion, and it fuels the dedication and discipline he needs at Suzuki.

Even when he was a teen, and bought his first bike, an innocuous Honda 50. Blackwell agreed to a deal with his parents. As long as he kept his grades high, he could ride, but if they dropped, he was on foot. As it turned out, Blackwell’s enthusiasm proved infectious for the family. Everytime he bought a bike, so did his father. Jack, so they could ride together. Eater, when he purchased a Hodaka. his father did as well, then when Blackwell began to race motocross, so did his 40-year-old father.

Early on in his racing career, Blackwell hooked up with Edison Dye, the father of motocross in America. Dye also just happened to be the importer for Husqvarna motorcycles, and the connection w'ould prove to be invaluable for Blackwell, whose first job for Dye in 1970 was to drive a chase van across Europe for Dye’s Alpine motorcycle tours. “1 was only 1 7 and I would get up in the mornings, throw the riders' baggage in the van, drive all day to the next stop, then eat wonderful food and drink great wine. And I got paid to do it,” he recalls.

Remembering those early days, Blackwell says, “I had two goals. I wanted to be the U.S. champion, and I wanted to be the world champion in motocross.” While riding Husqvarnas for Dye in 1971, Blackwell won the AMA national motocross championship, and the next season saw him headed for Europe to take on the world. ”1 struggled all year to get into the top 10,” he said. “I suffered engine failures, or mechanical failures throughout the entire year.” Then, to top off the disappointing season, he was hit in the eye with a rock at Luxembourg, the site of the last race. As a result, he was in the hospital for three weeks, and lost some vision in his left eye. Blackwell struggled for the championship for the next several years, but, in reality, the quest ended with the eye injury.

Oddly, Blackwell was not all that disappointed, because he had been feeling the urge to do “something else.” That something else would put him on a path seldom traveled by championship racers: “I was uneasy with the way things were going,” he says, “and I had an increasing desire to go back to school and learn more. I was especially interested in business. But, still, I wasn’t quite ready to give up racing.” By 1975, Blackwell was racing only a few select national events, and. soon after, began teaching a motocross school for Suzuki while taking night courses to earn his college degree.

After several years as the team manager for Suzuki’s motocross team, guiding it to five national titles, Blackwell returned to Husqvarna as product manager and assistant to the general manager in 198 1. By the time he became the vice-president of marketing, he had turned the American division of Husqvarna into a moneymaking company for the first time since Dye began importing the Swedish machines in the Sixties. “I had it great at Husqvarna,” he says. “I was able to go to school, but at the same time I was getting valuable on-thejob training that would have been almost impossible to get anywhere else.”

Leaving Husqvarna in 1986, Blackwell returned to Suzuki, but this time he was on the management staff, not the racing department. As the national advertising manager, he handled the media relations, but did not have a direct hand in the kinds of motorcycles that Suzuki was designing and bringing to America. He was, however, to have an immediate impact on some of the then-current models. After he rejoined Suzuki, he began to recruit key members of his staff from Husqvarna, so by 1987 that crack dirt team tackled the RM250 motocrosser, which had been languishing at the back of the pack for several years. Immediately, the RM began to improve under his staff’s influence.

INSIGHTS

IT'S LATE NIGHT. ABOUT 11:30. After dinner in Antonello’s restaurant, with his tie still tight around his collar, Mark Blackwell and 1 listen to the Italian bartender tell us a story of going to watch Giacomo Agostini at the Italian roadraces. Blackwell leans forward, his elbows resting lightly on the wooden counter, as the bartender recounts of whipping a scooter to the races and how Agostini destroyed the rest of the field. “Oh, he was beautiful,” he said. “He would bend the bike through the turns, so smoothly.” Blackwell, caught up in the story telling, alive to the bartender’s memory, tells of meeting Agostini. The bartender, so pleased that Blackwell had that opportunity, pours him a grappa, “from Antonello.” This, I think, is the essential Blackwell, deeply in love with motorcycles, whether he has a hand in making them, or sharing someone’s experience about watching them.

Camron E. Bussard

JLHF.N. IN LATE 1987. WHEN Tadaomi Shigenoya became the vicepresident of American Suzuki, he moved Blackwell up to the marketing director position, one step down from the top. Blackwell says, “Shigenoya understands the American culture better than most Japanese executives, and he has a tremendous grasp of the American market.” Blackwell works closely with Shigenoya, directing the overall Suzuki game plan in America, and he works closely with the parent company in Japan on models for the American market. Bikes like the Katanas and the new GS500 exist in large part to his urgings. He hints of more innovative machines to come, but he is also one of the most tight-lipped men in the business, so he gives few clues about future motorcycles coming from Suzuki.

It is the work with the new and future models that is the blessing and the curse for Blackwell. “We struggle and argue to get Japan to make the machines we want, but often we don't get what we desired. But then, when I have been working nonstop for days, and have been on the phone or in meetings, I stop and take a walk around the building. I come upon something like the GSX-R750 and I can't help but look at that and feel good about what I am doing. In no other industry do you get to work with anything as exciting as the new motorcycles.”

Some think that Blackwell is so driven that he would chew tin foil if it would help Suzuki. But it is important to remember that as one of the most powerful Occidentals in a business controlled by Japanese, Blackwell has to keep a professional pace not just with his American associates, but with his tireless counterparts working in Japan. “I am not a workaholic,” he says, “but I am goal driven, and once I achieve my goals, I like to spend a little time enjoying them before I move on to the next.”

Nonetheless, with the talent and desire that Blackwell has for marketing and business in general, you have to wonder how long the small world of motorcycling will be able to keep him happy. “No one can say what they will be doing in the future,” he says, “but right now I am committed to make Suzuki the best motorcycle company in the world. And we still have a long way to go. The bottom line is I love motorcycles; they are what got me started, and they are the fun in the job.” S