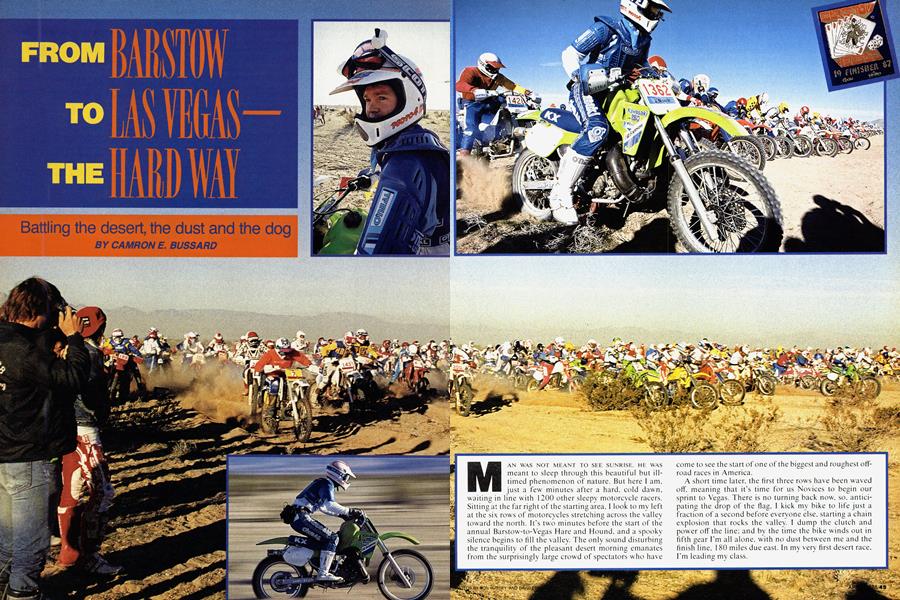

FROM BARSTOW TO LAS VEGAS— THE HARD WAY

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

Battling the desert, the dust and the dog

MAN WAS NOT MEANT TO SEE SUNRISE, HE WAS meant to sleep through this beautiful but illtimed phenomenon of nature. But here I am. just a few minutes after a hard, cold dawn, waiting in line with 1200 other sleepy motorcycle racers. Sitting at the far right of the starting area, I look to my left at the six rows of motorcycles stretching across the valley toward the north. It's two minutes before the start of the annual Barstow-to-Vegas Hare and Hound, and a spooky silence begins to fill the valley. The only sound disturbing the tranquility of the pleasant desert morning emanates from the surprisingly large crowd of spectators who have come to see the start of one of the biggest and roughest offroad races in America.

A short time later, the first three rows have been waved off. meaning that it's time for us Novices to begin our sprint to Vegas. There is no turning back now, so, anticipating the drop of the flag, I kick my bike to life just a fraction of a second before everyone else, starting a chain explosion that rocks the valley. I dump the clutch and power off the line; and by the time the bike winds out in fifth gear I'm all alone, with no dust between me and the finish line, 1 80 miles due east. In my very first desert race. I’m leading my class.

Suddenly, I come to my senses. I hate racing. What am I doing?

Well, it all began back in August, when I decided to ride the B-to-V race, held each year just after Thanksgiving. At the time, it sounded like a great way to spend the holiday weekend. But by the time the word spread among my friends that I had entered the race, I began to have second thoughts. Calls started coming in that made me feel the way the Coyote must when he realizes he has just run off a cliff while chasing the Roadrunner. One friend sauntered into my office with the encouraging words, “Good—now I can see what brain-dead looks like. I rode the race two years ago, so I know what it feels like. But now I’ll get to see it.” I started to worry.

Our resident desert and B-to-V expert, Ron Griewe, kindly proposed an alternative to the race when he offered to come over to my house that weekend and beat me with a rubber hose. “That way,” he said, “at least you’ll be in familiar surroundings for your torture.” Griewe then began to talk about how rough the course would be, mostly because of the whoops. Millions of whoops. Whoops spawning whoops. Big whoops, little whoops, belly-deep whoops, table-deep whoops and, oh, yeah, endless crossgrain whoops, whatever those are. I almost expected James Brown to jump in with a hot Rhythm and Blues number for background to Griewe’s endless litany of whoops.

I began to develop an ugly picture of what this race was all about, so I decided to get some professional help. First, I contacted Dr. Susan Hutchinson, a noted sports-medicine doctor and triathlete located in Irvine, California. I figured that a complete physical would get me started in the right direction, and that I could also get a few pointers about diet and training.

As I was sitting in the examination room, a lovely young woman entered and began asking me questions, including whether or not I was an athlete. I couldn’t believe she was the doctor, but I still straightened up, sucked in my stomach and pushed out my chest just a little, trying to disguise my slightly out-of-shape and marginally overweight body before reluctantly replying, “No.”

I told her that I didn’t train, I hated to work out, and I probably would do little exercise before the race. What I needed was a way that I could get ready for a long-distance off-road race without turning into a Bruce Jenner. I was 32 years old and doing this race for fun, I said, so I saw no reason to make myself suffer with a grueling training regimen beforehand; the race itself would be punishment enough. But I did tell her that a week before the race I would avoid cigars, french fries and ice cream; after all, no pain, no gain.

In spite of my resistance, Dr. Hutchinson was able to offer some good advice for those of us who hate to exercise. She said that, because I refuse to work out, one of the best things I could do was avoid the last-minute panic to get in shape. “Don’t start running and lifting weights a week before the race,” she admonished. “All that will do is get you fatigued by racetime.” Also, she advised against carbo-loading, a technique by which sharply honed athletes first deplete the body of carbohydrates about a week before a big competition, then, a day or two prior to the event, pack up on foods rich in carbos—things like green vegetables and pasta. “Those who aren’t used to it,” she said, “would do better to stick with normal diets.”

She also advised that in the week preceding the race, I drink as much water as possible, and avoid drinking anything that dehydrates the body. Alcohol is the big dehydrator, followed by caifine—which meant no beer or wine, and worse yet, no coffee. “During the race,” she suggested, “try to take in as much cold water as possible.” Water keeps the muscles loose and helps prevent cramps; and cold water moves from the stomach to the muscles more quickly than warm.

After I got the physical okay from the doctor, I decided it was time to get in touch with my inner self. My biorhythms looked good, according to the machine that swallowed several of my quarters, so I then consulted the stars. My neighbor is an out-of-work astrologer, so I thought I could give him a bit of work. At first he was ecstatic, but when I told him I wanted to know how I would finish and what troubles I could expect during the race, he told me to check back with him in a couple of days. When I did, I learned he had slipped out of town and was last seen heading for the Universal Harmonic Convergence in Maui. That left me with the good physician’s advice, which seemed sound enough, and my own discretion, which had gotten me into this mess in the first place.

I decided that the best strategy for the race would be to ride at a relaxed pace and enjoy it. My goal was simply to finish, so I dismissed any crazy ideas about being a dirtbike hero obsessed with winning. That freed me from the need to do anything stupid or dangerous during the race. I wanted to have fun, and began thinking of the event as a long, fast trail ride.

That was a fine idea, but as soon as the flag dropped on race day, all thoughts of fun and trail rides disappeared; I was out to win my class. I started in the fourth row, which took off nearly an hour after the Expert riders had left. Because there would already be over 600 riders ahead of me before I even started my engine, I decided that I wasgoing to pass riders, not be passed by them.

But I hadn’t considered the dust—or the insanity of my fellow racers. Three miles from the start, the dust was so thick, the early morning light disappeared. In what I thought was an early dusk, I found myself surrounded by hundreds of crazed racers all compelled into the darkness by the dream of glory or the dread of defeat. I couldn’t see where I was going, but if I slowed down at all, 10 guys would fly past and vanish into the purgatorial darkness. We were the restless shades from Hades, speeding along in a murky rampage, lacking form or substance. Or so it seemed until I hit a deep drainage ditch in fifth gear. The way I bashed my body off of the gas tank rudely reminded me of my mortality.

By the first gas stop—which seemed several hundred miles into the race but was actually only about 45 miles from the start—the pack had started to thin out just a bit, with wounded riders and broken bikes strewn along the trail. At this point, the dust had turned from a dark gray to a golden brown, looking a lot like the skies over Los Angeles on a particularly smoggy day.

From the first gas stop to the third, my race was uneventful. I managed to pass a lot more riders than passed me, and I had several good dices along the way. The terrain varied from deep silt beds to pea gravel, from hardpack fireroads to sandwashes, with plenty of rocks thrown in to keep everyone honest. And Griewe’s infamous whoops began a few miles from the start and ended just a few miles before the finish.

I was amazed at how many spectators were scattered along the course. And at one point, while clawing through a tight sandwash, I came across a guy who was leaning on his bike and intently watching a mutt of a dog irrigating the shrubbery. Geez, I thought to myself, this race must be really boring to watch if that is more interesting than what’s happening on the course. No accounting for taste, I figured.

At the Nevada border crossing, 40 miles from the finish, the terrain suddenly got much more rugged and demanding. I felt strong and was still passing people, even catching some riders who had started several rows ahead of me. But on a long, dry lakebed, as I finally got around a clump of riders I had been trying to pass for miles, I hit a rock and threw the chain. When I inspected the damage, I was sure my race was over, and that I’d have to spend the night huddled around my BIC lighter. The chain-adjuster nuts and their accompanying back-up plates had vibrated off of both sides. This allowed the rear axle to slide so far forward that the chain jumped the sprocket and got tightly wedged between the wheel hub and the swingarm.

If I’d had a clearer head at the time, I could have been back on the trail in five minutes; but after 150 dusty, punishing miles, my mind was a little fuzzy. So it took me over 30 minutes to repair the bike enough to get back in the race. And without any secure way to keep the rear axle in place, I had to ride at a vastly reduced pace. So, as I limped the last 20 miles to the finish, I had to watch helplessly as many of the riders I had overtaken earlier zipped past me like I was going 30 mph in reverse.

In the end, the fact that I finished was of little consolation, even though that was all I had set out to do. It was quite a letdown to have finished only in mid-pack after running at the front of my class earlier in the event. The overall winner, Darin Cartwright, finished nearly three hours ahead of me, having fought with second-place finisher Paul Krause for the whole race and beating him by only a few feet. Sure, they were Experts, but I despaired at finishing so far behind them.

Still, it wasn’t until after the race that I made my biggest mistake: I told.someone about the guy I had seen watching the dog urinate in the sandwash. Someone then informed me that that hadn’t been just any guy, or just any dog; the guy was a rider who raced the event with the dog on his tank, and the two of them had beaten me by at least 20 minutes. They must have passed me while I was broken down.

Now, it’s bad enough getting beat by Pros, but I can’t quite handle getting beat by a dog. Right then and there, I decided to enter the race again next year. I’m not going to care about winning, or even where I place in my class; all I am going to care about is beating that damned dog. I’m going to be gunning for him.

And you’d better believe that this time, I’m gonna listen to my doctor and get on an athlete’s diet; and I’m going to start training for the race right now—or, at least, as soon as I return from Maui and a long discussion with that coward of an astrologer. I plan to upset his converging harmony for not telling me months in advance about those loose adjuster nuts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

April 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

April 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

April 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1988 -

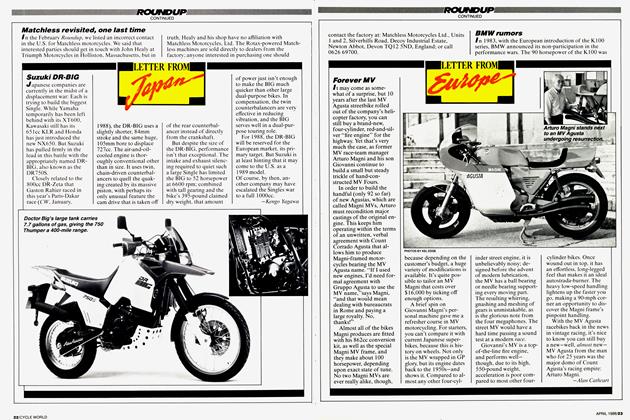

Roundup

RoundupYen And the Art of Motorcycle Marketing

April 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1988 By Kengo Yagawa