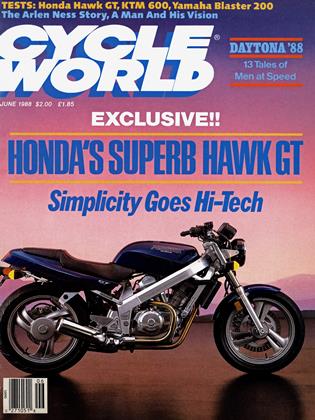

HONDA HAWK GT

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Bird of a Different Feather

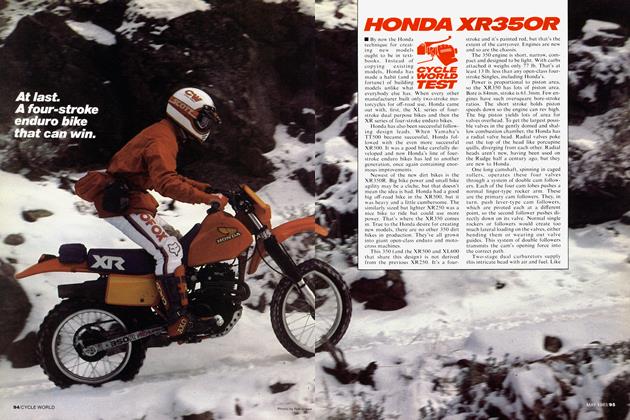

HONDA COULD HAVE NAMED IT JUST ABOUT ANYthing. It could have been called the Anti-Replica, as it was dubbed on an early, hastily translated technical report that came from the factory in Japan. Or it could have been called the UC650, because other documents referred to it as an "unclassified motorcycle." And it just barely escaped the misfortune of being called the Bros, its official moniker in other countries around the world.

But the name that finally emerged from American Honda’s what-do-we-call-it think-tank was “Hawk GT,” borrowing heavily from a designation the company had used twice before. The Hawk name appeared on a reasonably successful line of 400cc Twins in the mid-Seventies, but more important, it was first bestowed on another unclassified, anti-replica motorcycle the company introduced more than two decades ago: the 250cc Hawk. That original Hawk and its 305cc derivative, the Super Hawk, are credited with catapulting Honda from a maker of pleasant little motorized toys to the largest motorcycle manufacturer in history; and the company would love nothing more than for this latest Hawk to be just as significant as the first.

For good reason. To say that 1987 wasn’t a good year for Honda is like saying 1968 wasn’t a good time to vacation in Da Nang. Financially, last year was the worst in the company’s history. And falling sales and rising yen demanded that something different be done.

That something, Honda felt, was to answer a groundswell of cries for simpler motorcycles—for the return of the Twin, for the return of non-roadrace-replica sportbikes, even a few lonesome cries for the return of the 305 Hawk. But as a Honda spokesman pointed out, “We couldn’t just start building the 305 again. It would cost just as much to make as a modern motorcycle. . . and it would be awful."

The Hawk GT is Honda’s initial response to those passionate pleas for more-rational motorcycles. It’s a do-everything, 647cc Twin built through the simple execution of modern technology. It is a mix of*old and new, a bike with one wheel firmly planted in the traditions of yesterday and the other rolling boldly into the technology of tomorrow.

For example, the Hawk is powered by a V-Twin motor, among the most old-fashioned of all configurations, yet it has three-valve-per-cylinder combustion chambers and is liquid-cooled. The bike is unfaired, just like those fondly remembered standards of the Sixties and Seventies, yet it has an aluminum-beam frame like those on the sportbikes and roadracers of the Eighties. And it uses a massive, single-sided swingarm on which the disc rear brake mounts in the center of a concave rear wheel, pointing the way to what we might expect from the bikes of the Nineties.

So, despite its namesake, the Hawk can’t truly be called a back-to-basics motorcycle. In simplest terms, it is a modern, twin-cylinder sportbike, sans fairing. That’s .v/;<9/7bike, however, not racebike or racer-replica.

Rest assured, though, that the Hawk has just as much agility as most modern sportbikes, and is even more agile than some. With quick geometry and fat tires on wide, 1 7inch wheels at both ends, it responds immediately and positively to the rider’s every input. That it legitimately is an under-400-pound motorcycle with a comparatively low center of gravity doesn’t hurt one bit, either. It flicks over into corners with almost no effort whatsoever, and has enough cornering clearance to make the rider’s eyes real big before anything touches down. Overall, it gives the rider the feeling that he or she can do practically anything.

With those kinds of capabilities, the Hawk begs to be pushed to its handling limits—limits that are extreme on the street. Only when a very good rider is attempting his best Wayne Gardner imitation do the Hawk’s handling shortfalls make themselves known. The first thing the rider might notice is that the non-adjustable fork is a little soft, diving under hard braking. The rear end, too, isn't up to ten-tenths riding levels and tends to feel mushy at speed. It’s spring-preload adjustable, but offers no damping options.

But for virtually any other kind of riding, the suspension at both ends is more than adequate. The ride is smooth and comfortable in a wide variety of environments, anywhere from the freeway to the bumpiest backroad.

It’s interesting to note that the Hawk's rear suspension works quite well without any sort of linkage system; the bottom of the Showa shock bolts directly to the massive swingarm to produce only a mild amount of springing and damping progression at the rear wheel. The only apparent disadvantage is that the shock must sit higher in the chassis than on, say, a 600 Hurricane; but on the Hawk, that simply makes room for the 2-into-1 exhaust system’s large “boom box” tucked away under the front part of the swingarm. That, in turn, allows the Hawk to have a respectable amount of power, yet make little exhaust noise despite having a very short muffler.

Both the power and the sounds that emanate from the Hawk are very satisfying. Satisfying, at least, if you like riding a bike with immediate throttle response. Ánd satisfying if you want a 650 that pulls from low rpm like a 750 and sounds like it’s pulling from low rpm like a 750. Instead of making an anemic drone at 3000 rpm. the Hawk beats out a rhythmic tune that no one could possibly find offensive.

In terms of outright performance, the GT is comparable to Honda’s most recent lightweight sportbike, the Interceptor 500. If you’ve never sampled a VF500, then imagine a bike that has a smooth, progressive powerband and a respectable, if less than awesome, peak power output. The biggest differences are that the Hawk makes much better power off the bottom, and has a lower redline.

But that redline is easy to overstep; because at 8500 rpm, when the tach is telling you to shift, the engine is still making good power and telling you to stay on the gas. Soon after that, though, the V-Twin suddenly stops revving, and you have to look for a new gear ratio. So, if you plan on picking any fights on a Hawk GT, 500 Interceptors and Kawasaki EX500s are good candidates; you’ll have more bottom-end and less weight, and you’ll sound better.

But Honda didn’t just stumble onto such graceful engine characteristics; the Hawk’s powerplant has evolved quite a bit since first making its way to America in the 1983 VT500 Ascot. That 491cc, shaft-drive V-Twin wasn’t around very long, though, for dealers had a tough time moving them off their showroom floors. So, althou

the engine continued to evolve, it did so not in America but in other models sold in other countries.

For the engine’s return to the U.S., Honda played displacement games in an attempt to find the best power characteristics. The engine was built in prototype form as a 583, a 639 and a 655 before Honda finally settled on 647cc. The bike’s amiable powerband indicates that Honda’s engineers weren’t suffering from a case of indecision, but knew what they wanted and achieved it.

Interestingly enough, however, they didn’t do so by breaking any new technological ground. Even though the Hawk looks like nothing else that has ever graced two wheels, little about it is absolutely new. The single-sided swingarm and inboard rear disc are directly off the VFR750R Wayne Gardner Replica that is unavailable in this country; although no other Honda currently sold in the U.S. uses an aluminum frame, the VFR750 and 700 both had beam-type aluminum frames much like the Hawk’s; and a number of similar chassis have been available on some European and Japanese Honda models.

What is new is that all these high-tech tricks are available at once on a bike that doesn’t fancy itself either a roadracer or a drag-strip demon, a motorcycle that is as much at home on city streets as it is on backroads. Really, the only environment in which the Hawk can’t quite hold its own is on that long, lonesome highway, when you’ve got 500 miles to go before sunset. Its motor is smooth and vibration-free, but the seat is rather thin and begins to pain the posterior after an hour or two. Moving around to find new positions doesn’t help much; the seat’s step locks the rider into position. The only consolation is that your passenger has an even worse seat, and probably won’t let you go very far without a break.

You can keep on riding for a while if you’ve got an exceptionally tough butt and no passenger to toss out the anchor, but the rest of your body will probably give in before long. The bike’s footpegs are about as high as those on any current sportbike, and the handlebars have a distinct sporting flavor, as well. The bars are fairly high compared to those on the true repli-racers, but they’re still low by most other standards; and because they’re of the cast variety, they cannot be changed for something a little higher. So, as they are, they contribute to the bike’s rather cramped riding position. In fact, the entire motorcycle is small and better-suited for smaller riders.

Surprisingly, though, there isn’t much else to complain about on this mostly-new, first-year model. Okay, so the engine does tend to bake the rider’s right leg in hot weather. And there’s the smallish fuel-tank capacity, which will have you planning your trips around gas-station locations.

But there’s plenty to praise, too. In fact, one simple feature is enough to nominate this bike for the Motorcycle Medal of Good Taste: It has a centerstand. You learn to appreciate a centerstand on hot days, when the motorcycles all around yours have fallen over with their sidestands burrowed into semi-melted asphalt. Still more proof that the designers of this machine actually rode motorcycles is in the set of little bungee-cord hooks behind the passenger seat. Perhaps this isn’t an original idea, but the Hawk’s are positioned much better than those of the Kawasaki Ninja, which has had them since 1984.

Things like that are evidence that, unlike many of the plastic-coated flash machines of the day, the Hawk isn’t intended to be a status symbol or proof of manhood; it’s a motorcycle designed simply to be ridden by people. Real people, not racers and wannabe racers. It still is a sportbike, to be sure; to call it a standard motorcycle in the traditional sense of the word—or in the spirit of the original Hawk—would be wrong. But the Hawk GT is a much more rational sportbike, one with the emphasis less on “sport” and more on “bike.”

That qualifies it as a success no matter what it does for Honda’s bank balance. S

HONDA HAWK GT

$3995

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDown But Not Out

June 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeMoto-Immortality

June 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsAlas, Albion

June 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1988 -

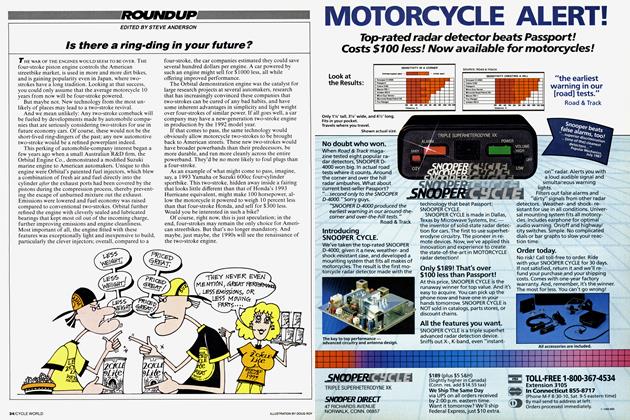

Rondup

RondupIs There A Ring-Ding In Your Future?

June 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Rondup

RondupLetter From Japan

June 1988 By Kengo Yagawa