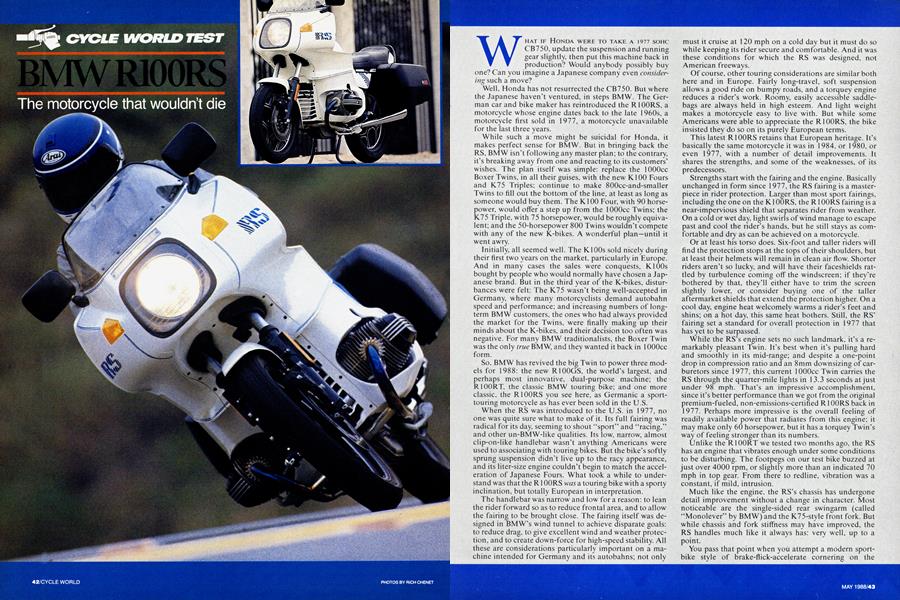

BMW R100RS

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The motorcycle that wouldn't die

WHAT IF HONDA WERE TO TAKE A 1977 SOHC CB750, update the suspension and running gear slightly, then put this machine back in production? Would anybody possibly buy

one? Can you imagine a Japanese company even considering such a move?

Well, Honda has not resurrected the CB750. But where the Japanese haven't ventured, in steps BMW. The German car and bike maker has reintroduced the R100RS, a motorcycle whose engine dates back to the late 1960s, a motorcycle first sold in 1977, a motorcycle unavailable for the last three years.

While such a move might be suicidal for Honda, it makes perfect sense for BMW. But in bringing back the RS, BMW isn’t following any master plan; to the contrary, it’s breaking away from one and reacting to its customers' wishes. The plan itself was simple: replace the lOOOcc Boxer Twins, in all their guises, with the new K100 Fours and K75 Triples; continue to make 800cc-and-smaller Twins to fill out the bottom of the line, at least as long as someone would buy them. The K100 Four, with 90 horsepower, would offer a step up from the lOOOcc Twins; the K75 Triple, with 75 horsepower, would be roughly equivalent; and the 50-horsepower 800 Twins wouldn’t compete with any of the new K-bikes. A wonderful plan—until it went awry.

Initially, all seemed well. The KlOOs sold nicely during their first two years on the market, particularly in Europe. And in many cases the sales were conquests, KlOOs bought by people who would normally have chosen a Japanese brand. But in the third year of the K-bikes, disturbances were felt: The K75 wasn’t being well-accepted in Germany, where many motorcyclists demand autobahn speed and performance; and increasing numbers of longterm BMW customers, the ones who had always provided the market for the Twins, were finally making up their minds about the K-bikes, and their decision too often was negative. For many BMW traditionalists, the Boxer Twin was the only true BMW, and they wanted it back in 1 OOOcc form.

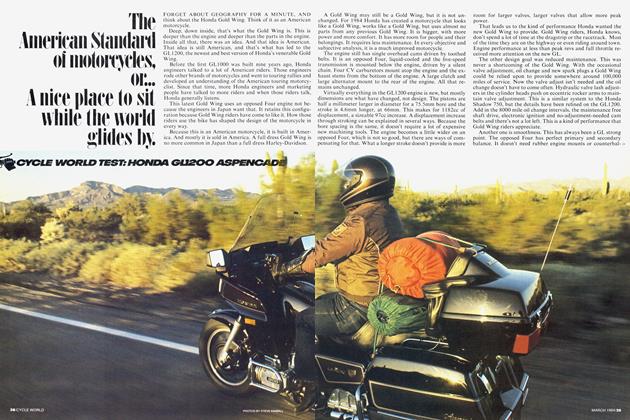

So, BMW has revived the big Twin to power three models for 1988; the new R100GS, the world’s largest, and perhaps most innovative, dual-purpose machine; the R100RT, the classic BMW touring bike; and one more classic, the R100RS you see here, as Germanic a sporttouring motorcycle as has ever been sold in the U.S.

When the RS was introduced to the U.S. in 1977, no one was quite sure what to make of it. Its full fairing was radical for its day, seeming to shout “sport" and “racing," and other un-BMW-like qualities. Its low, narrow, almost clip-on-like handlebar wasn't anything Americans were used to associating with touring bikes. But the bike’s softly sprung suspension didn’t live up to the racy appearance, and its liter-size engine couldn’t begin to match the acceleration of Japanese Fours. What took a while to understand was that the R1OORS was a touring bike with a sporty inclination, but totally European in interpretation.

The handlebar was narrow and low for a reason: to lean the rider forward so as to reduce frontal area, and to allow the fairing to be brought close. The fairing itself was designed in BMW’s wind tunnel to achieve disparate goals: to reduce drag, to give excellent wind and weather protection, and to create down-force for high-speed stability. All these are considerations particularly important on a machine intended for Germany and its autobahns; not only must it cruise at 120 mph on a cold day but it must do so while keeping its rider secure and comfortable. And it was these conditions for which the RS was designed, not American freeways.

Of course, other touring considerations are similar both here and in Europe. Fairly long-travel, soft suspension allows a good ride on bumpy roads, and a torquey engine reduces a rider’s work. Roomy, easily accessible saddlebags are always held in high esteem. And light weight makes a motorcycle easy to live with. But while some Americans were able to appreciate the R100RS, the bike insisted they do so on its purely European terms.

This latest R100RS retains that European heritage. It’s basically the same motorcycle it was in 1984, or 1980. or even 1977, with a number of detail improvements. It shares the strengths, and some of the weaknesses, of its predecessors.

Strengths start with the fairing and the engine. Basically unchanged in form since 1977, the RS fairing is a masterpiece in rider protection. Larger than most sport fairings, including the one on the K100RS, the R100RS fairing is a near-impervious shield that separates rider from weather. On a cold or wet day, light swirls of wind manage to escape past and cool the rider’s hands, but he still stays as comfortable and dry as can be achieved on a motorcycle.

Or at least his torso does. Six-foot and taller riders will find the protection stops at the tops of their shoulders, but at least their helmets will remain in clean air flow. Shorter riders aren’t so lucky, and will have their faceshields rattled by turbulence coming off the windscreen; if they’re bothered by that, they’ll either have to trim the screen slightly lower, or consider buying one of the taller aftermarket shields that extend the protection higher. On a cool day, engine heat welcomely warms a rider’s feet and shins; on a hot day, this same heat bothers. Still, the RS' fairing set a standard for overall protection in 1977 that has yet to be surpassed.

While the RS’s engine sets no such landmark, it’s a remarkably pleasant Twin. It's best when it's pulling hard and smoothly in its mid-range; and despite a one-point drop in compression ratio and an 8mm downsizing of carburetors since 1977, this current lOOOcc Twin carries the RS through the quarter-mile lights in 13.3 seconds at just under 98 mph. That's an impressive accomplishment, since it’s better performance than we got from the original premium-fueled, non-emissions-certified R100RS back in 1977. Perhaps more impressive is the overall feeling of readily available power that radiates from this engine; it may make only 60 horsepower, but it has a torquey Twin’s way of feeling stronger than its numbers.

Unlike the R100RT we tested two months ago, the RS has an engine that vibrates enough under some conditions to be disturbing. The footpegs on our test bike buzzed at just over 4000 rpm, or slightly more than an indicated 70 mph in top gear. From there to redline, vibration was a constant, if mild, intrusion.

Much like the engine, the RS's chassis has undergone detail improvement without a change in character. Most noticeable are the single-sided rear swingarm (called “Monolever" by BMW) and the K75-style front fork. But while chassis and fork stiffness may have improved, the RS handles much like it always has; very well, up to a point.

You pass that point when you attempt a modern sportbike style of brake-flick-accelerate cornering on the BMW. When you go deep into a turn and chop the throttle, the rear suspension—which was being extended by the shaft-drive-induced torque reaction while you were on the gas—sags, momentarily unweighting the rear wheel just as engine-braking loads the rear tire. This feels unsettling, and gives you your first shot of adrenaline. Then, as you brake hard, the front end dives, seemingly to excess, before porpoising back up when you release the brake. You try to flick the RS on into the corner, and the leverage provided by the narrow handlebar doesn’t seem much better than if you were trying to turn by grabbing the fork tubes. Then, as you gas the RS out of the corner, the sudden application of power causes the back of the bike to rise, another disturbing sensation. You quickly gather that this is not the way to ride a BMW.

Whether you like it or not, the BMW forces a riding style that emphasizes smoothness. Long-time BMW riders (the ones who go fast, anyway) use the engine to slow early for corners, take a smooth, flowing line through the turns on constant throttle, and rolllll the throttle open. The engine’s strong mid-range complements this technique, and while the pace might be a hair’s-breadth slower than with a racier style, the RS now at least cooperates.

This need for smoothness arises from several sources: the relatively soft springing, the shaft drive, the longish suspension travel, the fairly pronounced engine braking. But modern motorcycle engineering leaves little reason for a bike to force its preference on the way you ride; BMW knows how to cure every one of these problems without harming ride quality. The first step would be to endow the RS with BMW’s new Paralever rear suspension that reduces shaft-drive effects, and is this year used exclusively on the R1OOGS.

Nevertheless, once you adapt to the RS, it feels quite natural. Being smooth on this bike is its own reward and, along with the soothing beat of its Twin, allows you to cover many miles of twisty road quickly while staying fresh and relaxed.

Those curvy two-lane roads are where the RS is most at home. On American interstates, the bent-forward riding position seems way out of place, and in the long run is uncomfortable (although recent Japanese racer-replica sportbikes have riding positions that make the RS’s feel mild by comparison). Neither is the hard seat on the RS much good on interstates, but it is perfectly acceptable on roads that force you to move around at least slightly.

In the end, the RS works best for a particular rider, one who wants good weather protection, a responsive and mellow engine, a light and simple touring motorcycle. It’s for a rider who wants to ride two-up comfortably, who covets the ability to cover curvy miles quickly, but not at anything like a racing pace.

In other words, the RS is a sportbike for grownups.

And while perhaps BMW should have further refined it before bringing it back, the RS as it stands is a good motorcycle, one that deserves its revival. As BMW makes it better in future years, its attraction can only grow.

BMW

R1OORS

$7750