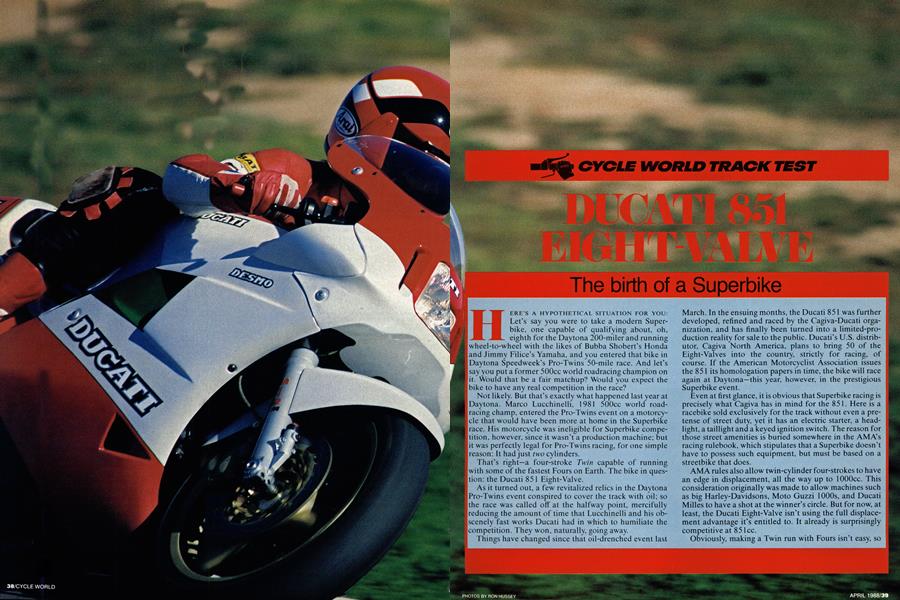

DUCATI 851 EIGHT-VALVE

CYCLE WORLD TRACK TEST

The birth of a Superbike

HERE'S A HYPOTHETICAL SITUATION FOR YOU: Let's say you were to take a modern Superbike, one capable of qualifying about, oh, eighth for the Daytona 200-miler and running wheel-to-wheel with the likes of Bubba Shobert's Honda and Jimmy Filice's Yamaha, and you entered that bike in Daytona Speedweek's Pro-Twins 50-mile race. And let's say you put a former 500cc world roadracing champion on it. Would that be a fair matchup? Would you expect the bike to have any real competition in the race?

Not likely. But that's exactly what happened last year at Daytona. Marco Lucchinelli, 1981 500cc world roadracing champ, entered the Pro-Twins event on a motorcy cle that would have been more at home in the Superbike race. His motorcycle was ineligible for Superbike compe tition, however, since it wasn't a production machine; but it was perfectly legal for Pro-Twins racing, for one simple reason: It had just two cylinders.

That's right-a four-stroke Twin capable of running with some of the fastest Fours on Earth. The bike in ques tion: the Ducati 85 1 Eight-Valve.

As it turned out, a few revitalized relics in the Daytona Pro-Twins event conspired to cover the track with oil; so the race was called off at the halfway point, mercifully reducing the amount of time that Lucchinelli and his ob scenely fast works Ducati had in which to humiliate the competition. They won, naturally, going away.

Things have changed since that oil-drenched event last March. In the ensuing months, the Ducati 851 was further developed, refined and raced by the Cagiva-Ducati orga nization, and has finally been turned into a limited-pro duction reality for sale to the public. Ducati's U.S. distrib utor, Cagiva North America, plans to bring 50 of the Eight-Valves into the country, strictly for racing, of course. If the American Motorcyclist Association issues the 85 1 its homologation papers in time, the bike will race again at Daytona-this year, however, in the prestigious Superbike event.

Even at first glance, it is obvious that Superbike racing is precisely what Cagiva has in mind for the 851. Here is a racebike sold exclusively for the track without even a pre tense of street duty, yet it has an electric starter, a head light, a taillight and a keyed ignition switch. The reason for those street amenities is buried somewhere in the AMA's racing rulebook, which stipulates that a Superbike doesn't have to possess such equipment, but must be based on a streetbike that does.

AMA rules also allow twin-cylinder four-strokes to have an edge in displacement, all the way up to 1000cc. This consideration originally was made to allow machines such as big Harley-Davidsons, Moto Guzzi 1 000s, and Ducati Mules to have a shot at the winner's circle. But for now, at least, the Ducati Eight-Valve isn't using the full displace ment advantage it's entitled to. It already is surprisingly competitive at 851cc.

Obviously making a Twin run with Fours isn't easy, so the 85 1 engine is not just an old Ducati motor with some extra cams and valves thrown in; this engine is fundamentally new. It’s liquid-cooled, itself a Ducati first, with redesigned centercases that accept a six-speed, close-ratio gearbox. The overhead cams are still belt-driven, but now there are two of them per four-valve cylinder. The included angle between intake and exhaust valves is 40 degrees, much narrower than on previous Ducatis to allow a more-efficient combustion-chamber shape. Thanks to Ducati’s desmodromic (mechanically opened and closed) valve-actuation system, there are no valve-spring pockets for the ports to be routed around, so the intake tracts run almost dead-straight into the combustion chambers. And the 851 is fuel-injected, eliminating the need for complicated downdraft carburetors.

That fuel-injection system is fairly simple, a WeberMarelli electronic unit similar to the one Ferrari uses on its Formula One racecars. The computerized system is entirely reprogrammable—that is, if the mixture isn’t quite spot-on at any point in the rpm range, it's possible to plug a computer into the system and change its parameters. A nifty concept, even if making those mixture-ratio changes does require someone who is computer-literate and has the software needed to reprogram the system.

Like its engine, the 851’s chassis has little in common with past Ducatis—or, for that matter, past Cagivas. Despite common ownership, Ducati and its parent firm, Cagiva, still are quite different companies that haven’t entirely integrated as one; each still has separate engineers working on separate projects. The 750 Paso chassis, for example, was a Cagiva project, and the 851 shares practically nothing with it, aside from a footpeg bracket here and a shift linkage there.

But despite being almost entirely a product of the Ducati factory in Bologna, the Eight-Valve also is quite different from Ducati’s own recent series of 750cc F1/ Montjuich/Laguna Seca production racebikes. The 85l’s frame is a configuration unto itself, though it bears much similarity to a successful Ducati TT Formula 1 frame built a few years ago by innovative Spanish chassis designer Antonio Cobas. The frame uses a much steeper steeringhead angle than do other big Ducati streetbikes, with the exception of the Paso.

The rear suspension is different, as well. Older Ducatis use a series of levers and links to operate a shock located under the fuel tank, but the 85 1 has a more upright shock that is compressed from both ends—from the top by a large, overhead rocker-arm connected to the swingarm legs via a link rod on each side, and from the bottom by the front of swingarm itself. It’s a layout similar to the Full Floater system used on the first Suzuki single-shockers in the early Eighties. Up front, a sturdy Marzocchi M1R fork with externally adjustable rebound damping handles the suspension chores.

In essence, then, the 851 is new from nose to tail. More important, it seems to be reasonably competitive with the best four-cylinder Superbikes in the world—no small accomplishment for a Twin. We’re not just taking Lucchinelli’s word for it, either; we saw it for ourselves when we track-tested the 851 at Riverside Raceway, spending an entire day flogging this exciting machine through some of the fastest turns in California.

And the first thing we noticed about riding the world’s most competitive V-Twin was that the combination of sensations you experience is ... is all wrong. To begin with, you don’t expect to start a full-on racebike by touching a button and hearing an electric motor crank the engine to life. Not only that, any European Twin so highly tuned that it can run with Japanese Fours should have the manners of a rabid pit bull. You expect it to sputter and cough at low rpm, maybe puke a little raw gas out the intake, and suffer from an awful case of megaphonitis, to boot. But the 851 isn’t like that at all. Even as it eases through the pits it is impressively civilized, carburating at least as well as any Ducati we’ve ever ridden, with nary a cough, gag or sputter.

Out on the track, your senses still get mixed inputs as the Eight-Valve winds up to peak rpm, for what you see and feel doesn’t jibe with what you hear. Some of your senses are assaulted by relentless. Superbike-fierce acceleration, but the air is filled with the bark and bellow of a big VTwin rather than the screech and wail of a Four. Besides, the engine doesn’t vibrate enough to justify the thunderous, V-Twin hammering that rolls out of the 2-into-2 exhaust system. But the Ducati is dead-smooth, actually shaking and rattling less than most Japanese streetbikes. All wrong.

You learn to ignore those discrepancies quickly enough, but you continue to encounter other inputs that just don’t add up. The engine, for example, redlines at 10,000 rpm and continues to pull strongly up until the injection systern cuts the fuel supply at 10,500 rpm, but it nonetheless pulls impressively hard as low as 5000 or 6000 rpm.

You don 7 learn to ignore that; you learn to use it to your advantage. Not many other racebikes would still let you turn excellent lap times if you lugged the engine 4000 rpm below its power peak. Certainly, most competitive Superbikes wouldn’t. And a stock Yamaha FZR750R definitely wouldn’t.

We know this to be true, for when we went to Riverside to test the 85 1, we took along an FZR750R for comparison purposes. We didn't have an AMA Superbike laying around, but we did have an FZR in our shop; and we figured that it is about as close to a production Superbike as is available in this country. Since the 85 1 professes to be just that kind of motorcycle, we felt the FZR would be a perfect match for it.

Wrong again. On the track, the Ducati was superior in nearly every way to the Yamaha. Not only did the 851 walk away from it in roll-on acceleration tests—we expected that much from a V-Twin with a lOOcc displacement advantage—but it kicked the Yamaha’s fanny in corner-to-corner acceleration and top speed, as well. Every time the two bikes would exit a corner together, the Ducati would stretch out its long legs and flat run away from the FZR. And at the end of Riverside’s long back straight, our radar gun caught the Ducati at 1 52 mph, whereas the Yamaha couldn’t top 144.

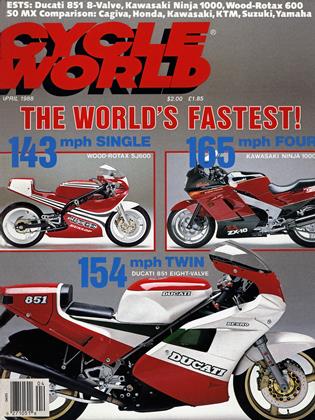

Both bikes, particularly the Ducati, had a bit more speed in them, but not enough space at Riverside to use it. So, a few days later, we took the 851 out to a long, straight, desolate stretch of road in the desert to find out just how fast it would go. But, alas, 40to 50-mph crosswinds blew through the area all day, and the Duck managed only 1 54 mph on its best run, during which it had to bank over into the wind at about a 20-degree angle while going straight ahead. The bike had to be back at Cagiva the very next day for an AMA homologation inspection, so we never had a chance to see how fast it would really go. But we feel that under the right conditions, the 85 1 could easily nudge the 160-mph mark.

Now, some of you might question our enthusiasm about the Ducati’s prodigious power output, seeing as how our FZR is a 750cc streetbike that’s legal in 49 states, while the Ducati is an 851cc pure racer that would give an EPA inspector bad dreams for a month. But at Riverside, even the 85 l’s chassis was more than a match for the Yamaha’s. The 445-pound Ducati always felt wonderfully light and responsive, almost seeming to change direction at the very thought of turning; yet at speed, it was as stable as a threestory townhouse. By comparison, the Yamaha felt cumbersome and twitchy, even though it is nothing of the sort.

One area where the FZR did have the upper hand was its front fork. The rear-suspension behavior of both bikes was comparable, but the Ducati’s Marzocchi fork was consistently harsh around Riverside’s bumpy course, often causing the bike to chatter and be imprecise over little ripples at high speed. The Yamaha was able to soak up these same track imperfections much more efficiently.

But in all honesty, that's about the only complaint we can muster. The Ducati is a masterpiece of civility, even though it doesn’t have to be. If it vibrated a little, no one would care. If it fell out of the powerband 1500 rpm below redline, no one would be surprised. And if it were a raspy, sputtering collection of bad manners, no one would mind. After all, it is a racing Twin that can blow the fairing off any production Four in the 750 class. But there are no catches; the Ducati doesn't force you to tolerate any undesirable behavior.

Well, there is one catch. About $20,995 worth of one. That’s how much Cagiva North America wants for an 851. And not only do you have to cough up that kind of money, but Cagiva has to decide if it wants to let you have one. The bikes will be sold though Cagiva dealers, but a potential buyer first has to send a resume with his racing and riding history to Cagiva.

On top of that, although the 851 is the most competitive Twin to hit Superbike racing in a decade, it’s not quite capable of winning a Superbike main event. Not, at least, as delivered from Cagiva. The engine is in practically the same state of tune as the one in Lucchinelli’s 1987 Daytona machine, but that bike would have qualified only seventh or eighth for last year’s 200-miler. The 1988 crop of four-cylinder Superbikes will be faster yet, so the 851 has its work cut out for it if it is to be a serious contender for a spot on the victory podium.

On the other hand, there is more potential in the 851 than demonstrated in our test. A thorough race-prep would surely rid the bike of 40 or 50 unwanted pounds as unnecessary items such as the electric starter, the sidestand and the lighting equipment were eighty-sixed and the stock 2-into-2 exhaust system traded for a lighter 2-into-l like the one Lucchinelli used. That exhaust system would also yield a tad more power, presumably, as would a bit of additional engine hot-rodding and blueprinting. After all that, the 851 might, with a top-rate rider aboard, contest for a Superbike win. But that the bike is competitive at all is amazing, a tribute to the talent of its creators—Massimo Bordi, the brilliant young protégé of the famous “father of Ducati motorcycles,” Ing. Fabio Taglioni; and Franco Farnè, Ducati’s long-time chief of development.

All things considered, then, that $21,000 ante might seem like a mighty high buy-in. But when you’re selling something no one else offers, you usually can name your own price. And right now, there is no other Twin made that can match the 85 1. Hell, there aren’t that many Fours that can match it.

So, no, Cagiva isn’t planning to sell 851s to everyone. Just to racers who want something they can’t get anywhere else—and are willing to pay for it. 0

$20,995

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

April 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

April 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

April 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupYen And the Art of Motorcycle Marketing

April 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1988 By Kengo Yagawa