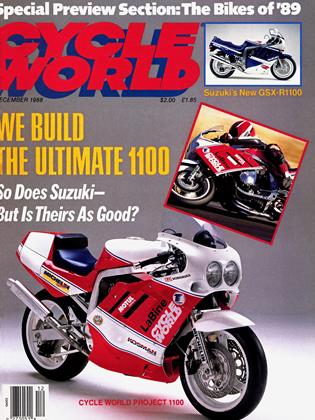

PROJECT GSX-R ENDURANCE RACER

What do you get when you stuff a hopped-up 1100 engine in a 750 chassis? A marriage made in heaven and a bike that goes like hell.

PAUL DEAN

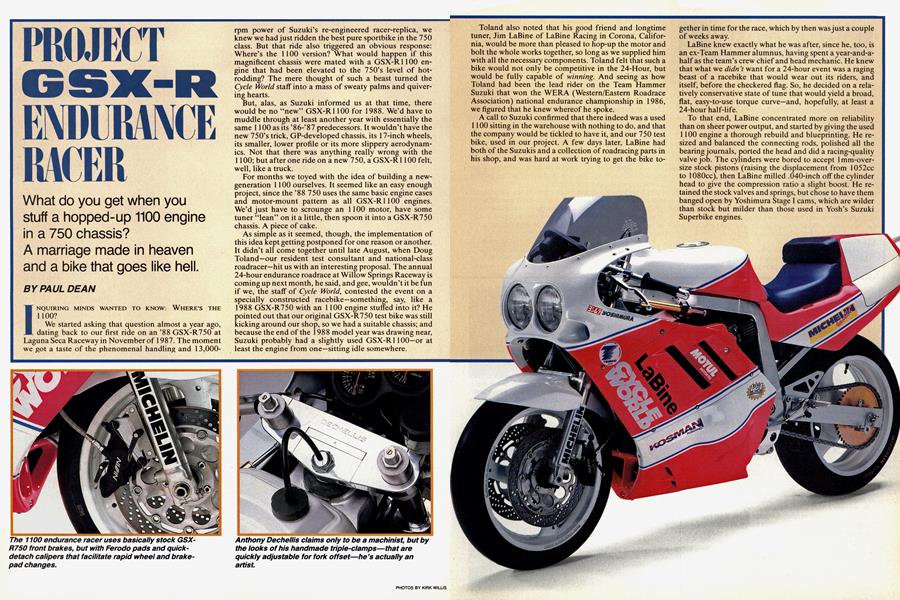

INQUIRING MINDS WANTED TO KNOW: WHERE'S THE 1100? I We started asking that question almost a year ago, dating back to our first ride on an 88 GSX-R750 at Laguna Seca Raceway in November of 1987. The moment we got a taste of the phenomenal handling and 13,000-

rpm power of Suzuki’s re-engineered racer-replica, we knew we had just ridden the best pure sportbike in the 750 class. But that ride also triggered an obvious response: Where’s the 1100 version? What would happen if this magnificent chassis were mated with a GSX-R1100 engine that had been elevated to the 750’s level of hotrodding? The mere thought of such a beast turned the Cycle World staff into a mass of sweaty palms and quivering hearts.

But, alas, as Suzuki informed us at that time, there would be no “new” GSX-R1100 for 1988. We’d have to muddle through at least another year with essentially the same 1100 as its ’86-’87 predecessors. It wouldn’t have the new 750’s trick, GP-developed chassis, its 17-inch wheels, its smaller, lower profile or its more slippery aerodynamics. Not that there was anything really wrong with the 1100; but after one ride on a new 750, a GSX-R1100 felt, well, like a truck.

For months we toyed with the idea of building a newgeneration 1100 ourselves. It seemed like an easy enough project, since the ’88 750 uses the same basic engine cases and motor-mount pattern as all GSX-R1100 engines. We’d just have to scrounge an 1100 motor, have some tuner “lean” on it a little, then spoon it into a GSX-R750 chassis. A piece of cake.

As simple as it seemed, though, the implementation of this idea kept getting postponed for one reason or another. It didn’t all come together until late August, when Doug Toland—our resident test consultant and national-class roadracer—hit us with an interesting proposal. The annual 24-hour endurance roadrace at Willow Springs Raceway is coming up next month, he said, and gee, wouldn’t it be fun if we, the staff of Cycle World, contested the event on a specially constructed racebike—something, say, like a 1988 GSX-R750 with an 1100 engine stuffed into it? He pointed out that our original GSX-R750 test bike was still kicking around our shop, so we had a suitable chassis; and because the end of the 1988 model year was drawing near, Suzuki probably had a slightly used GSX-R1100—or at least the engine from one—sitting idle somewhere.

Toland also noted that his good friend and longtime tuner, Jim LaBine of LaBine Racing in Corona, California, would be more than pleased to hop-up the motor and bolt the whole works together, so long as we supplied him with all the necessary components. Toland felt that such a bike would not only be competitive in the 24-Hour, but would be fully capable of winning. And seeing as how Toland had been the lead rider on the Team Hammer Suzuki that won the WERA (Western/Eastern Roadrace Association) national endurance championship in 1986, we figured that he knew whereof he spoke.

A call to Suzuki confirmed that there indeed was a used 1100 sitting in the warehouse with nothing to do, and that the company would be tickled to have it, and our 750 test bike, used in our project. A few days later, LaBine had both of the Suzukis and a collection of roadracing parts in his shop, and was hard at work trying to get the bike to-

gether in time for the race, which by then was just a couple of weeks away.

LaBine knew exactly what he was after, since he, too, is an ex-Team Hammer alumnus, having spent a year-and-ahalf as the team’s crew chief and head mechanic. He knew that what we didn 7 want for a 24-hour event was a raging beast of a racebike that would wear out its riders, and itself, before the checkered flag. So, he decided on a relatively conservative state of tune that would yield a broad, flat, easy-to-use torque curve—and, hopefully, at least a 24-hour half-life.

To that end, LaBine concentrated more on reliability than on sheer power output, and started by giving the used 1100 engine a thorough rebuild and blueprinting. He resized and balanced the connecting rods, polished all the bearing journals, ported the head and did a racing-quality valve job. The cylinders were bored to accept lmm-oversize stock pistons (raising the displacement from 1052cc to 1080cc), then LaBine milled .040-inch off the cylinder head to give the compression ratio a slight boost. He retained the stock valves and springs, but chose to have them banged open by Yoshimura Stage I cams, which are wilder than stock but milder than those used in Yosh’s Suzuki Superbike engines.

PROJECT RACER

To further quicken the acceleration, LaBine exchanged the 1100’s crankshaft-mounted electric-starter clutch for the 750’s; the latter is considerably lighter and smaller, so it reduces overall crankshaft inertia. He also kept the 1100’s five-speed gearbox rather than swap it for a sixspeed. The six-speeders were designed for a 750, and their long-race durability is suspect when stressed with the massive power of an 1100.

LaBine surprised even us with his conservatism by retaining the 750’s stock, 36mm Mikuni CV carbs (breathing through K&N air filters), rather than do the usual and fit 38mm smoothbores. “I’ve seen these 750 carbs on a flow bench,” he explained, “and they flow more air than the 1100 head does. So, I don’t think they’ll hurt the power much at all, and they should give good, smooth response coming out of corners.” He also had Power Sports build a custom exhaust system that not only fit this hybrid, but complemented the engine’s wide powerband. The pipe even incorporated an exceptionally quiet but efficient silencer that the riders would grow to appreciate during the 24-hour grind.

When he got to the chassis, LaBine left the basic 750 frame and swingarm alone, believing that both were easily up to the task. But he felt the need to tinker with quite a

few other chassis components, either for added durability, improved performance or easier adjustability. The rear shock, for instance, was an off-the-shelf Fox Twin Clicker aftermarket unit, but equipped with a LaBine-designed hydraulic preload adjuster built by his friend, supermachinist Anthony Dechellis.

Other LaBine/Dechellis collaborations on the bike included: a ride-height adjuster built into the top shock mount; rugged triple-clamps adjustable for fork-tube offset; an aluminum-billet fork brace much stronger in all planes than the stocker; a clutch-cover spacer that allowed the use of a simple, cable-operated clutch rather than the more-complicated stock hydraulic mechanism; fork-tube extenders that permit the clip-on handlebars to be mounted above the triple-clamps (preferred by some endurance-race teams for long-term rider comfort, although we left our bars below the clamps); and brake-caliper brackets front and rear that allow the calipers to be removed (for wheel and brake-pad changes) just by pulling an aircraft-style quick-release pin.

Although many of Dechellis’s handmade pieces were still in the final stages of development, most were so beautifully machined and polished that they looked like works of modern art. LaBine’s ultimate goal is to ensure that they all work as good as they look, then to begin distributing them through his racing shop.

Fine workmanship also was evident in the rear wheels made especially for the GSX-R by Kosman Racing. At 3.5 inches wide, the 750’s stock, 17-inch front wheels were perfectly sized for the Michelin bias-ply slicks we wanted to run up front; but the 17-inch rear wheels, at 4.5 inches, were too narrow for the Michelin radial slicks we needed in the rear. We couldn’t locate enough sufficiently wide racing wheels (we needed three sets) in time for the race; so we sent three stock rears to Kosman, who machined off their outside edges and welded on wider bead flanges, ending up with the required 5.5-inch wheel width. We were amazed, but Sandy Kosman says he’s been widening wheels for years, and will perform similar surgery on practically any cast wheel for $350 a shot.

All that remained for LaBine, then, were numerous final details. He made special brackets to adapt the 1100 oil cooler to the 750 frame (the 750’s cooler is larger but won’t fit due to the bigger motor’s higher exhaust-port location). He installed a Yoshimura heat shield between the carbs and the cylinder head, and, to facilitate speedy gas stops, welded a dry-break quick-filler neck into the stock 750 fuel tank. He fitted the front brakes with handmade, steel-braided lines, and slipped in the very latest racing pads from Ferodo. While he was at it, he popped the dished anti-rattle washers on the floating front brake rotors over-center by hitting them with a hammer and punch, allowing the rotors to float more freely. A steering damper from White Power was mounted between the left fork tube and the left-side main frame beam, and a Tsubaki Sigma O-ring chain was laid over the PBI finaldrive sprockets.

To brighten the nighttime racing picture, LaBine gave the GSX-R 230 watts of portable daylight by wiring the stock halogen headlights to put all four beams—the 55-

watt low beams and 60-watt high beams of both lights—on the job at all times. He then adjusted the lights to aim distinctly upward, but pointing away from one another. This resulted in a rather dim view of straightaways in the dark, but provided enough illumination in most corners to allow surprisingly fast running through the pitch-blackness of the desert night.

Finally, we took the GSX-R’s bodywork to Steve Harris in San Pedro, California, for its stunning, neon-pink-andwhite paint job. Harris has laid custom paintwork on quite a few famous racing vehicles, including Terry Vance’s Pro Stock Suzukis and Kenny Bernstein’s Funny Cars. Thanks to his fine handiwork, our Suzuki was unquestionably the brightest, most-attractive motorcycle at Willow Springs that weekend. And, as you are about to read in the story that follows, it was also unquestionably the fastest.

If we decide to race the bike again, though, it might have lots of close competition. As we learned midway through this project (and as you can read in the preview section of this issue), Suzuki will finally have a new GSX-R 1100 for 1989; and to no one’s surprise, it is conceptually very similar to ours—but in street trim, of course. One significant difference is that Suzuki’s 1100 will use the big Katana’s 1127cc engine instead of the 1052cc motor from the ’86’88 GSX-R 1100.

At this point, it’s impossible to know whether or not Suzuki’s new 1100 will be faster or better than ours, especially on a racetrack. But if it hopes to be either, it had better be one fantastic motorcycle. Because the 1100 you see here is just that. ES

Suppliers

Engine, chassis building Jim LaBine Racing 11731 Sterling Ave., Unit A Riverside, CA 92503 (714) 689-0112

Camshafts, oil, carb shields Voshimura R&D of America 4555 Carter Court Chino, CA 91710 (714) 628-4722

Tsubaki chain UST, Inc. 12275 E. Slauson Ave. Whittier, CA 90606 (213) 726-8313

Exhaust system Power Sports 24715 LaCresta Dana Point, CA 92629 (714) 240-0465

Tires Michelin Tire Corp. P.O. Box 19001 Grennville, SC 29602 (803) 234-5000

Wheels Kosman Racing 340 Fell St. San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 861-4262

15500 S.E. 102nd. Clackamas, OR 97015 (503)655-5128 Brake pads

Ferodo Ltd. P.O. Box 15388 No. HOllYWOOd, CA 91615 (818)362-2705

Painting Steve Hams 242 West 17th St. San Pedro, CA 90731 (213)833-0261

Shock absorber Fox Factory, Inc. 544 McGlincey Lane Campbell, CA 95008 (408) 377-3422

Air filters K&N Engineering, Inc P.O. Box 1329 Riverside, CA 92502 (714) 684-9762

Engine covers, quick-fill neck Phil Scott 5803 Whispering Hills Blvd. Louisville, KY 40219 (502) 968-4629

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAdios, Specialization

December 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeEngineers

December 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Learnings

LearningsThe Buck-A-Day, 25-Year Habit

December 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupWhither the Passenger?

December 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1988 By Alan Cathcart