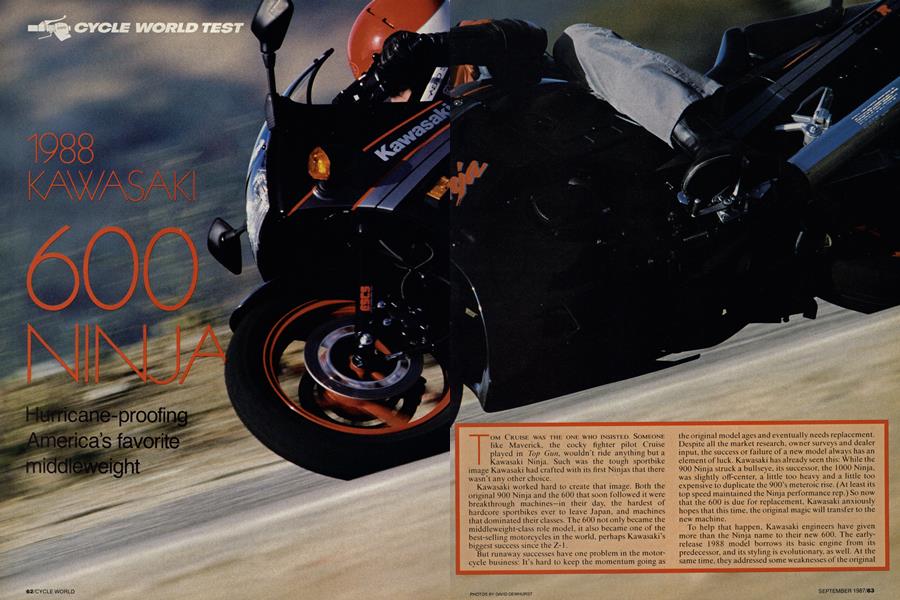

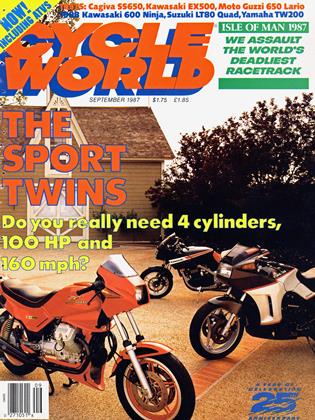

1988 KAWASAKI 600 NINJA

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Hurricane-proofing America's favorite middleweight

TOM CRUISE WAS THE ONE WHO INSISTED. SOMEONE like Maverick, the cocky fighter pilot Cruise played in Top Gun, wouldn't ride anything but a Kawasaki Ninja. Such was the tough sportbike image Kawasaki had crafted with its first Ninjas that there wasn’t any other choice.

Kawasaki worked hard to create that image. Both the original 900 Ninja and the 600 that soon followed it were breakthrough machines—in their day, the hardest of hardcore sportbikes ever to leave Japan, and machines that dominated their classes. The 600 not only became the middleweight-class role model, it also became one of the best-selling motorcycles in the world, perhaps Kawasaki’s biggest success since the Z-1.

But runaway successes have one problem in the motorcycle business: It’s hard to keep the momentum going as the original model ages and eventually needs replacement. Despite all the market research, owner surveys and dealer input, the success or failure of a new model always has an element of luck. Kawasaki has already seen this: While the 900 Ninja struck a bullseye, its successor, the 1000 Ninja, was slightly off-center, a little too heavy and a little too expensive to duplicate the 900’s meteroic rise. (At least its top speed maintained the Ninja performance rep.) So now that the 600 is due for replacement, Kawasaki anxiously hopes that this time, the original magic will transfer to the new machine.

To help that happen, Kawasaki engineers have given more than the Ninja name to their new 600. The earlyrelease 1988 model borrows its basic engine from its predecessor, and its styling is evolutionary, as well. At the same time, they addressed some weaknesses of the original 600; Engine hot-rodding has brought power up to 1987 standards, and a new frame has reduced weight for all the performance improvements a lighter bike can bring.

Carrying over to the 1 988 model, the Ninja’s 600cc engine has its roots in the air-cooled, two-valve-per-cylinder GPz550 motor, which itself sprang from the 1980 KZ550 design. These earlier Kawasaki engines lent their crank design, bore-spacing and transmission layout to the Ninja 600 engine, so it has an alternator mounted on its crank, a relatively long, 52.4mm stroke, and a two-stage primary drive; the crank drives a jackshaft via a silent chain, and a gear on the jack sha! t drives the clutch. But what made the Ninja a Ninja were the new parts added to the GPz foundation: the more compact crankcases, and, most especially, the big-bore, liquid-cooled, four-valve-per-cylinder top end.

It’s that top end that has seen most of the updates for 1988. The intake ports have had their roofs raised to straighten and improve air flow, and new pistons bring the compression ratio toa very high 1 1.7:1. while cam timing remains unchanged. Connecting rods are made from a stronger material, and piston pins are a millimeter larger for more durability; when you've been refining an engine as long as Kawasaki has this one, all the small weaknesses have made themselves known and offered themselves up to improvement.

I his refinement shows: The newest Ninja has the best engine in the middleweight class. Kawasaki claims 84 horsepower from it, one more than for Honda's powerhouse Hurricane, and our testing gives credence to that claim. The Kawasaki matches a 1987 Hurricane almost exactly during roll-ons from the highest engine speeds; from 9000 rpm on up, the Honda might have the slightest of power advantages, but the two are basically as close in top-end acceleration as two motorcycles can be. With the rider in full tuck, though, the Ninja (perhaps through more-aerodynamic design) out speeds the Hurricane by a phenomenal margin, raising the top-speed record for stock 600-class motorcycles from the Hurricane’s 134 mph all the way to 141. And in the mid-range, the Kawasaki eats the Hurricane alive, pulling multiple bike-lengths on it in a 60-to-80-mph top-gear charge. This is despite the fact the Honda is actually spinning 200 rpm faster at 60 mph.

That mid-range power gives the Ninja a bigger-than600cc engine feel. It pulls well from about 400CTrpm upward, with power increasing smoothly with speed. The rush becomes a little more frantic around 8000 rpm, but there’s never the sudden surge of an engine coming on the cam. Power continues well beyond the 1 1,000-rpm redline, with no sag until nearly 12,000 rpm. All in all, the performance is impressive for any engine, yet alone a middleweight whose roots go back at least eight years.

Housing the engine is a frame whose roots seemingly go back almost as far. Last year’s Ninja used a steel boxsection frame that swept around the outside of the cylinder head; this year’s bike uses a tubular steel frame with twin loops that wrap over the top of the engine, down to the swingarm pivot, under the engine and back to the steering head—yet another variation on the classic Norton Featherbed design.

Why this seeming retreat from modern, aluminumbeam practice? Weight, compactness and familiarity are the probable answers. Kawasaki has used a similar design for the 750 Ninja, and knew that with high-strength, largediameter round tubes, a frame could be made'both stiff and light. And without tubes wrapping around the outside of the cylinder head, the Ninja could be narrower.

Besides, the previous 600 Ninja frame may have owed its design more to fashion than to engineering.' While twinspar aluminum frames like Yamaha’s Deltabox design may wrap around the engine and be exceptionally stiff, small-section rectangular'tubing bent around the cylinders—as on the ’85-to-'87 600 Ninjas—instead of over the top may not. Better carburetor access on the original Ninja may have been purchased by a weight gain and no improvement in stiffness.

Whatever its rationale, the new chassis has produced a substantially lighter bike. Last year’s machine weighed 452 pounds dry. the '88 Ninja only 427. That’s two pounds less than a Hurricane and eight more than an FZ600, putting it right in the thick of the middleweight class. And whatever the Ninja’s actual weight, it feels lighter yet. The new machine carries its weight and rider low; seat height is less than 30 inches above ground level. And the garage test of straddling a bike and tossing it sideto-side might lead to a sub-400-pound guess on the Ninja’s weight, for it definitely has a lower center of gravity than a Hurricane.

The light feel continues when the Ninja is rolling. The light-flywheeled engine revs quickly, and hard acceleration in first gear has the front tire only tentatively touching the pavement. Even with firmer tire contact, the Ninja’s steering is very light. The bike flicks easily, and its front end feels very precise negotiating slow corners.

At freeway speeds, the steering borders on being slightly nervous for straight-line travel, responding to even the slightest rider input. Steering effort firms up at speeds considerably faster than our new national limit, but the Ninja always retains cat-quick steering. That’s its biggest point of contrast with Honda’s 600 Hurricane: The Honda feels bigger, heavier and more sluggish than the Ninja, particularly on roads with slow corners. There, the Ninja is simply more fun and easier to ride quickly. At three-digit speeds, the Hurricane needs a firm tug on its bars to deflect it from the straight ahead, the Ninja only a gentle pull. Accordingly, the Honda feels more stable, but during our testing, the Ninja never wobbled or misbehaved. Thus the new chassis is an improvement for riders seeking quick response. Comfort aspects of the new chassis are largely improvements, as well. Compared to some of the latest racer-replicas (GSX-Rs and FZRs), the riding position is less cramped. Just as on the previous Ninja, though, the footpegs are located close to the saddle. But the handlebars are reasonably high by the standards of the class, and the seat reasonably shaped, so a few-hundred-mile ride won’t leave you with muscle spasms and locked in pretzellike cohtortions. While passenger accommodations are still bad enough that no Ninja rider should put someone he cares for on the seat behind him, the Ninja overall rates as a pleasant sportbike perch for its pilot.

Nor does the suspension compromise streetability to achieve a racetrack edge. This latest Ninja is sprung firmly, but still responds well to freeway expansion strips and most small bumps. The front fork is equipped with KYB’s electric anti-dive system, which noticeably increases compression damping with brake application. That's a mixed blessing if you're trying to scrub ofl'a little speed with the front brake in the middle of a bumpy corner, but at least the anti-dive system can be adjusted for minimal effect.

The front brake itself is powerful, even if the lever is somewhat squishy. Only a light pull is required for a rearwheel-lifting stop; but under those conditions, the lever pulls in too close to the grip for a rider to leave two fingers around the throttle.

As a complete mechanical package, though, the new Ninja is a definite improvement over its predecessor. It accelerates harder, goes faster and handles better. Unfortunately, its appearance may be considered less of an improvement.

Motorcycle styling is always a question of personal taste, but to us, the new Ninja, with its knee-grip panels and dull paint scheme, isn't as distinctive or as attractive as its predecessor. The new bike looks as if it were built from the puree created by tossing every recent Kawasaki sportbike into a blender; the old 600 Ninja looked like nothing else, and simply had more flash.

Kawasaki’s engineers have done their job and produced a better bike, one that rivals Honda’s Hurricane for the best 600cc sportbike title. The Ninja matches the Hurricane strength-for-strength, such as in top-end performance, and excels in other areas, such as roll-ons, top speed and twisty-road handling. In those very specific ways, the ’88 Ninja matches or raises middleweight-class perform-

ance standards.

But will that be enough for the new Ninja to inherit past magic?

Kawasaki may discover that that type of magic has as much to do with style and image as with objective performance. Only time will tell if the ’88 Ninja 600 is the machine Maverick would choose.

1988

KAWASAKI

600 NINJA

$3899

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe High Cost of Higher Performance

September 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeCoached To Success

September 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1987 -

Evaluation

Evaluation"The Care And Feeding of Your Motorcycle"

September 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupGrass-Roots Saviors?

September 1987 By Charles Everitt -

Roundup

RoundupShort Subjects

September 1987