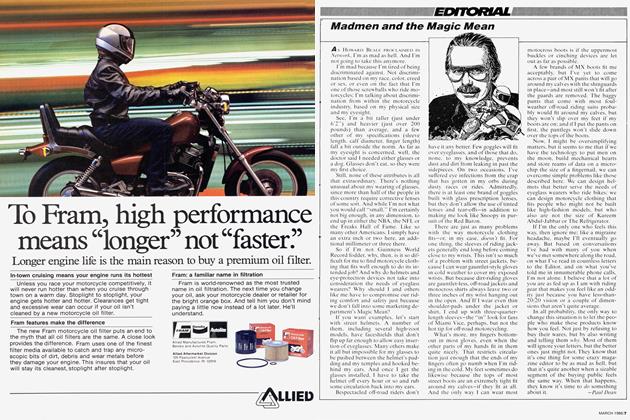

The high cost of higher performance

EDITORIAL

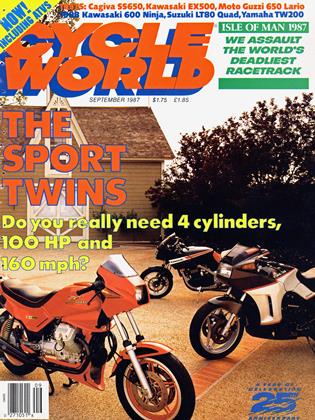

HERE'S TODAY’S QUIZ IN STREETBIKE Economics 101: How much is one more tenth of a second in the quarter-mile worth to you? How much are you willing to pay for one more mph in top speed or a 0.001-percent reduction in lap times around a road-race track? How much value do you place on always owning the hottest and most technologically sophisticated motorcycle on the market?

There are no right or wrong answers in this test; only you know what best meets your needs. But if your reply to any or all of these questions is “not very much at all,” you’re in the majority. Indeed, most motorcyclists don’t feel the burning need to get caught up in the ever-escalating performance and technology wars.

Recent sales numbers support that conclusion. By far, the fastest and most sophisticated motorcycles you can buy—and the ones that get more advertising space and magazine exposure than any other kind of twowheeler—are the racer-replica sportbikes. But despite all the hype that accompanies these corner-seeking street missiles, they usually don’t sell as well as most of the more-pedestrian models.

And for good reasons. Once machine sophistication exceeds a certain level, most riders are unable to perceive its advantages. There always is, of course, a small number of exceptional riders who can use and appreciate such extreme sophistication, but fewer and fewer of them are willing—or able—to pay for it.

Which brings us to the crux of the matter at hand here: Money. Bucks. Dinero. Moolah. Piles of it.

See, high performance is fun but it ain't cheap. Quite to the contrary, its cost tends to increase exponentially, making every added increment of performance many times more expensive than the one before it. Conceivably, a manufacturer could invest almost as much R&D money in knocking a couple of tenths off a bike’s quarter-mile ETs or lap times every year as it did in developing the entire machine in the first place. And achieving that higher level of performance usually requires more-expensive construction materials and manufacturing methods.

Guess who pays for all of this. Bingo! That’s right, Bunky, you pay. You pay directly when you buy those performance models; and sometimes you even pay indirectly when you buy one of that manufacturer’s other bikes. Why? Because a company’s investment in the development, manufacture or refinement of a maximumperformance bike often is too great to be fully recovered through the sales of just that one model; when that happens, some of that investment is offset by raising the prices of other bikes in the line.

One of the many messages I read in all of this is that unless something significant changes, the ongoing sportbike performance escalation we’re currently in the midst of cannot continue much longer. Otherwise, most motorcycles—sportbikes in particular-will soon cost so much that only the Malcolm Forbeses of the world will be able to afford them.

Already, in fact, motorcycle prices have risen dangerously high. The devaluation of the dollar certainly has added its fair share to price increases; but exchange rates aside, the truth is that by their very nature, repli-racer sportbikes have become considerably more expensive to manufacture—and, therefore, to buy— with each passing year.

Just look at what’s happening in Japan, where the 250cc and 400cc classes are caught up in an all-out technology war. The result is domestic-model sportbikes that are as sophisticated as GP roadracers, including some 400s that are faster than open-class streetbikes of 10 years ago. But some of those 250s have list prices of over $3000, and the trickest of the 400s costs more than $6000. If you use those numbers to project the probable cost of bigger bikes built with that same level of technology, you can see that $10,000 750s and 15-grand 1000s could be right around the corner.

Before you throw up your hands in despair, though, let me propose a solution, one suggested by Yamaha’s FZR750R: limited production.

In building the FZR750R, Yamaha wanted to offer the most competitive 750-class sportbike/productionracer it could for 1987; its marketing people, though, felt that the necessarily steep asking price for such a bike would put off most prospective mainstream buyers, but that a select few hard-core sport riders would be willing to cough up big bucks for a leading-edge machine. So Yamaha built only a very small number of the FZR750Rs and hung a hefty price tag on them, one that would make the bikes profitable to sell; but the company also continued to offer the masses a slightly improved version of the existing, moderately high-tech FZ750 (FZ700 in the U.S.), which could sell at a very competitive price. Thus, anyone who absolutely had to have the ultimate was able to get it— for a price, naturally—while buyers of other Yamahas who didn't want it or need it wouldn’t have to pay for it.

That seems an elegant solution to a knotty problem, one that the other Japanese manufacturers should seriously consider. It would allow them to continue their neverending pursuit of new technology and ever-higher performance—and to service the small number of enthusiasts to whom breakthroughs such as oval pistons and hub-center steering are important—without depriving the general riding public of affordable hardware.

This is, of course, an imperfect solution, one that would prove as unpopular with hard-core knee-draggers as mandatory training wheels. But considering the probable alternatives, it’s the best solution to the problem I’ve yet heard. —Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeCoached To Success

September 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1987 -

Evaluation

Evaluation"The Care And Feeding of Your Motorcycle"

September 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupGrass-Roots Saviors?

September 1987 By Charles Everitt -

Roundup

RoundupShort Subjects

September 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupEven the Police Feel the Need For Speed

September 1987