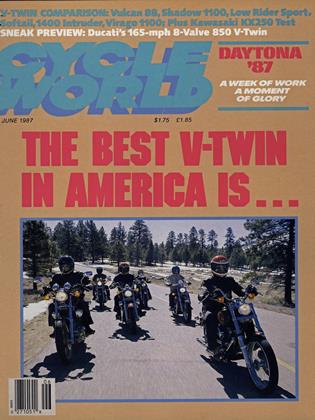

Mil-spec motorcycling

AT LARGE

WALKING OUT OF THE THEATER AFTER seeing Tom Cruise decimate the bad guys as Top Gun, I turned to young Andrew and asked if the movie made him want to fly an F-14.

"Nah," he said, "it makes me want to ride a Ninja."

I could see his point. Not everybody struggles through the program to become an F-14 jock, but just about anybody with the desire, the cash and the driver's license can become a Ninja rider. And as has been noted enough times to make it a cliché, flying and riding provide a lot of the same rushes. Which might explain why a lot of the pilots I know are also motorcyclists, and also why motorcycling continues to do a brisk business with military types.

Mostly unnoticed by the world outside the gates guarding our Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine bases, motorcycling has undergone something of a renaissance in the military. Fve listened to my friend Rear Admiral C. Barrett Laning talk about his adventures in the 1930s with his Indian 45, and the social ostracism the bike brought down on him from his stiff-necked colleagues—including his Academy classmates. His stories highlight what a breakthrough were Adm. Elmo Zumwalt’s famous ZGrams of the early 1970s, which began the liberation of motorcycles and motorcyclists on Navy bases—and in Navy minds. Considering that on most Navy bases, bikes were flatly outlawed, it needed to be done.

Bikes had never suffered quite the opprobrium on Army and Air Force bases that they did at Navy sites, but until the generations changed in the 1970s, they were still thought to be appropriate gear only for enlisted people. Officers were expected—if not required—to ride in Packards if they were desk warriors, or maybe Corvettes and E-Types if they were airplane jockeys or snake eaters. That this prejudice still exists to some extent was demonstrated to me a few years ago when I met Naval aviator Warren Harner at Summit Point raceway; Harner-then a Lieutenant senior-grade flying Lockheed P-3s— was a hot RZ350 racer. And as we talked about his experiences in the Navy, it became clear that he had en-

countered some social flak because of his motorcycle roadracing. Having taught a sportscar safety course to Air Force types with another aviatorroadracer. Major Herb Hester, and having roadraced in England myself while wearing a blue suit, I wasn’t surprised.

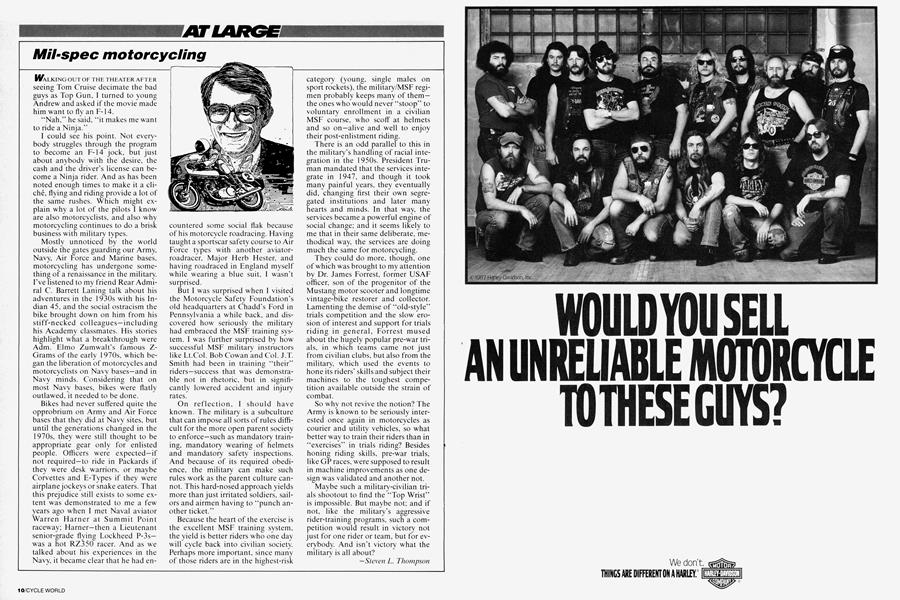

But I was surprised when I visited the Motorcycle Safety Foundation’s old headquarters at Chadd’s Ford in Pennsylvania a while back, and discovered how seriously the military had embraced the MSF training system. I was further surprised by how successful MSF military instructors like Lt.Col. Bob Cowan and Col. J.T. Smith had been in training “their” riders—success that was demonstrable not in rhetoric, but in significantly lowered accident and injury rates.

On reflection, I should have known. The military is a subculture that can impose all sorts of rules difficult for the more open parent society to enforce—such as mandatory training, mandatory wearing of helmets and mandatory safety inspections. And because of its required obedience, the military can make such rules work as the parent culture cannot. This hard-nosed approach yields more than just irritated soldiers, sailors and airmen having to “punch another ticket.”

Because the heart of the exercise is the excellent MSF training system, the yield is better riders who one day will cycle back into civilian society. Perhaps more important, since many of those riders are in the highest-risk

category (young, single males on sport rockets), the military/MSF regimen probably keeps many of them— the ones who would never “stoop” to voluntary enrollment in a civilian MSF course, who scoff at helmets and so on—alive and well to enjoy their post-enlistment riding.

There is an odd parallel to this in the military’s handling of racial integration in the 1950s. President Truman mandated that the services integrate in 1947, and though it took many painful years, they eventually did, changing first their own segregated institutions and later many hearts and minds. In that way, the services became a powerful engine of social change; and it seems likely to me that in their same deliberate, methodical way, the services are doing much the same for motorcycling.

They could do more, though, one of which was brought to my attention by Dr. James Forrest, former USAF officer, son of the progenitor of the Mustang motor scooter and longtime vintage-bike restorer and collector. Lamenting the demise of “old-style” trials competition and the slow erosion of interest and support for trials riding in general, Forrest mused about the hugely popular pre-war trials, in which teams came not just from civilian clubs, but also from the military, which used the events to hone its riders’ skills and subject their machines to the toughest competition available outside the strain of combat.

So why not revive the notion? The Army is known to be seriously interested once again in motorcycles as courier and utility vehicles, so what better way to train their riders than in “exercises” in trials riding? Besides honing riding skills, pre-war trials, like GP races, were supposed to result in machine improvements as one design was validated and another not.

Maybe such a military-civilian trials shootout to find the “Top Wrist” is impossible. But maybe not; and if not, like the military’s aggressive rider-training programs, such a competition would result in victory not just for one rider or team, but for everybody. And isn't victory what the military is all about?

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Crash Course In Career Counseling

June 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Shape of Things To Come

June 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

June 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

June 1987 By Alan Cathcart -

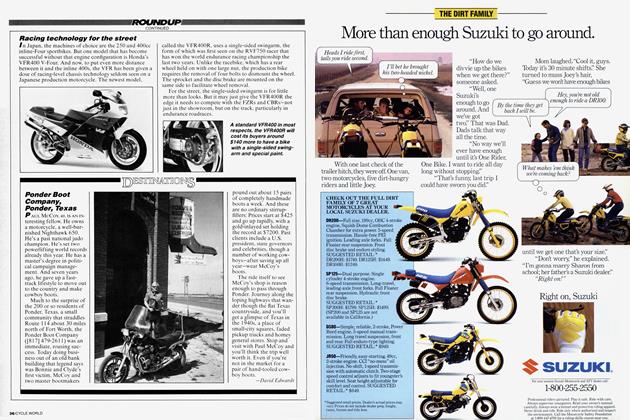

Roundup

RoundupPonder Boot Company, Ponder, Texas

June 1987 By David Edwards