Fear and loathing in the doubles

EDITORIAL

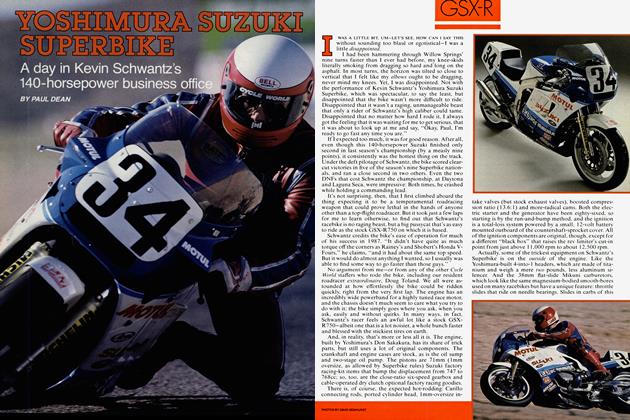

BACK WHEN IT WAS FIRST PROPOSED some 15 years ago, it seemed an absurd concept: motocross racing in a football stadium, of all places. But Mike Goodwin, the rock-concert promoter who conceived this idea of “indoor” motocross, never stopped believing in its huge potential for success, and pursued that dream with the tenacity of a runaway tank. His vision finally became reality in the Los Angeles Coliseum on a warm July evening in 1972; and from that point, stadium motocross steadily grew into this country’s most highly watched form of motorcycle racing.

It’s hard to measure the positive effects stadium racing has had on the sport of motocross, but they are many, no matter what the yardstick. Holding these events in the convenience and comfort of huge, urban sports facilities, combined with all the promotional hype and television coverage that often goes along with them, has worked wonders for public awareness of motorcycle racing.

But in the process, stadium racing—supercross, as it is now known— has changed the nature of motocross. Truth is, supercross is not “motocross” in the traditional sense of the word; the two differ in enough areas—track design, race format, rider strategy and bike setup, among other things—that they almost are entirely different activities.

Fundamentally, I have no problem with that difference; the more legitimate ways there are to sell motorcycle racing to the public, the better. But I don’t like the negative effects that indoor motocross has inadvertently had on outdoor motocross.

See, once supercross caught on, it didn’t take long before local-level outdoor tracks began looking like national-caliber indoor tracks. And it’s easy to understand why. Supercross races are held only a few times a year in select big-city sports stadia, and are open only to national heroes and, at best, a handful of top local Pros; supercross programs occasionally include amateur competition, but not always. The net effect is that the average rider has almost no chance of ever racing in a “real” supercross.

So, local race promoters, acting at the request of many of their regular riders—and, of course, believing that stadium-style tracks would be strong drawing cards—simply fired up their graders and started building purely artifical courses packed with the stuff of supercross: slow, sharply peaked jumps; long sections of deep, closely spaced whoops; “tabletop” jumps; lots of tight turns; and perhaps the most diabolical element ever to hit the sport—doubleand triple-jumps.

Now, within the tight confines of a stadium, those sorts of obstacles make sense. As Goodwin knew right from the start, you won’t draw much of a crowd to watch bikes simply dodge goalposts or ride over the pitcher's mound; you’ve got to have action, and a stadium track built with a good mix of the aforementioned obstacles keeps the joint full of leaping, bounding, turning—and, yes, sometimes even crashing— motorcycles all night long. But in the expansiveness of the outdoors, indoor-style tracks seem rather silly. And doubleand triple-jumps on local outdoor courses make no sense at all.

Why? Because such jumps are so intimidating that many riders won't attempt them. Often, even some riders at supercross events won't chance the doubles and triples—and they’re supposed to be the sport’s top guns.

The problem with jumps of this sort is that they’re an all-or-nothing proposition; you either attempt to jump the entire chasm, or forget about it and don’t try it at all. And there’s no way to learn how to do them a little at a time as you can with every other aspect of motorcycle rac-

ing. You can gradually learn how to slide a bike by drifting the rear wheel just a fraction of an inch farther each time until you get the hang of it. You can learn to do conventional jumps or bermed turns or deep whoops in the same way, biting off no more than you can chew at any given time.

But double-jumps aren't like that; from the first time you try one, you either do it right, flying at least as high and as far as the best riders do, or you fail, miserably and, very often, painfully. Even if you're an experienced double-jumper, the slightest bobble—a botched shift, a missed line, a hiccup in the engine—can put you in pain city before you know it. But if you don't “do the doubles,” you give up all chance of winning, and probably won't even finish up among the front-runners.

So, in effect, what double-jumps ask of a rider is to be a daredevil, an Evel Knievel, at least once a lap, all through the race. The 15 Buicks aren’t there to jump over, but you still might have to fly far enough to clear them. And that cold, hard fact of motocross life is not likely to help bolster the sagging ranks of motocross riders.

I’m not advocating the abolishment of double-jumps. But I am suggesting that anyone who builds doubles or triples on a motocross track— especially at the local level—use some common sense. With just a little ingenuity, these jumps could be designed so that riders who choose not to attempt them aren’t automatically relegated to a back-of-the-pack finish. And tracks open for public use between race events ought to provide separate areas where riders who don’t know how to double-jump could learn the right techniques a lot more safely. These areas need consist only of four or five doubles ranging from low, closely spaced ones to big ones like those out on the track. Riders could begin on the really easy jumps and, advancing at their own pace, work up to the full-sized ones.

That makes sense to me. Because if motocross keeps asking its aspiring young riders to take a crash course— literally—in the art of racing, motocross will soon have a shortage of aspiring young riders.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeProliferating Poseurs

March 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1987 -

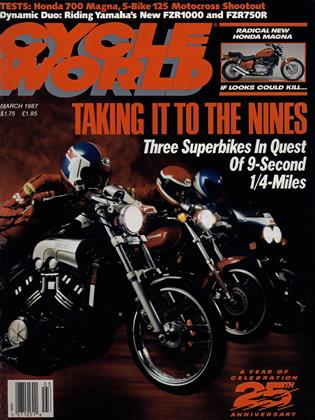

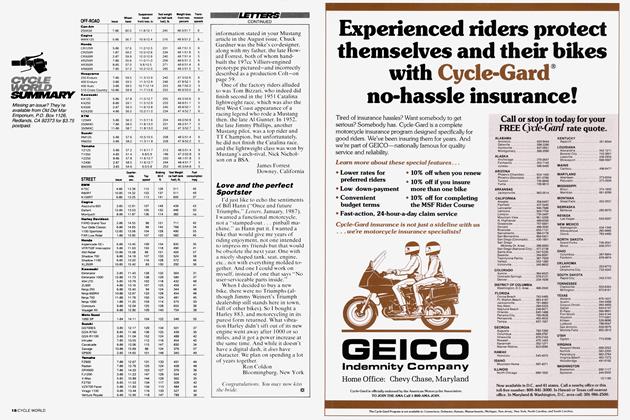

Cycle World

Cycle WorldSummary

March 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley-Davidson: Trading Motorcycles For Motorhomes?

March 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

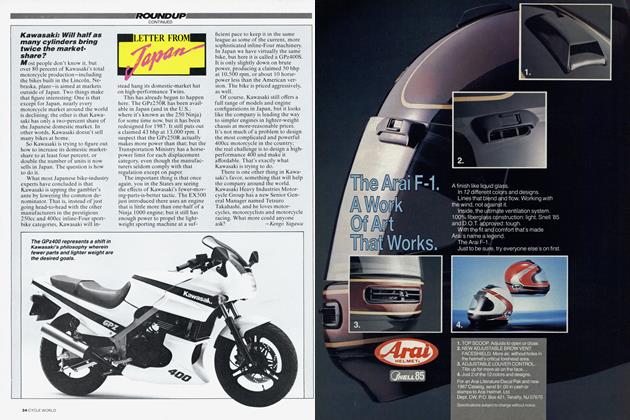

RoundupLetter From Japan

March 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

March 1987 By Alan Cathcart