Seoul-searching

EDITORIAL

WOULDN’T IT BE WONDERFUL, I REcently overheard someone say, if the motorcycle business were more like it was 20 years ago? If there were lots of inexpensive little entry-level bikes on the market just like back in the Sixties, this person proposed, more new riders would be attracted to the sport, and motorcycle sales wouldn't be dropping off the way they have been over the past few years.

These words of wisdom are brought to you compliments of a local motorcycle dealer, who uttered them while discussing the state of the bike business with a few customers in his shop. And while his solution to a complicated problem is rather simplistic, it still makes perfect sense to me. Matter of fact, in an April, 1986, editorial entitled “Back to square one?” I talked about the dearth of legitimate entry-level bikes in recent times, and the effect their absence has had on the industry. So I obviously agree—as do a lot of other motorcyclists, judging by the glut of mail I received on the subject after that issue hit the streets.

The problem, though, is that every time people start thinking about the entry-level problem, they automatically look toward Japan for solutions. They do that, no doubt, because for the last 25 years or so, that is where the answers to such questions have come from.

But Japan is not the same place it was back when we first started meeting the nicest people on a Honda. Not by a long shot. That little island in the Pacific is an unprecedented success story, rising from the ashes of World War II almost overnight to become the world leader in a wide variety of industries. Not surprisingly, the prosperity brought on by the meteoric success of Japanese manufacturing dramatically raised the standard of living in that country. But it also had an equally uplifting effect on the cost of designing, developing, manufacturing and marketing new products.

What all this means is that the economic conditions which allowed Japan to put America on two wheels during the Sixties and Seventies do not exist in the Eighties. So, the Japanese manufacturing empire that was founded on its ability to produce good, low-cost products—including small-displacement, entry-level motorcycles—at remarkably low prices is no longer able to do so.

It seems, then, that the answers will have to come from someplace else. Someplace that is not a developed manufacturing nation, but rather a developing manufacturing nation. Someplace where manufacturing capabilities and product quality are comparatively high, even though labor costs are quite low. Someplace, say, like South Korea.

Indeed, very quickly and quietly, Korea has become a strong force in the world market by manufacturing and exporting goods of reasonable quality that sell for some of the lowest prices in ages. This explains a tenfold growth in that country’s manufacturing output over the last three or four years. It’s no wonder that Korea is being called “the new Japan” by many people.

And for good reason. Although the standard of living in South Korea is up from where it was at the end of the Korean war, it’s nowhere near as high as Japan’s. Thus, the cost of manufacturing, which generally parallels the standard of living, is much lower in Korea. What’s more, while the Japanese yen has been rapidly rising in value relative to the U.S. dollar, the Korean won has been stable. And so far, the U.S. has not imposed any import restrictions on Korean-made goods. This makes America a receptive outlet for low-cost, good-quality products from Korea.

If you doubt that, ride over to your local K-Mart or any other discount store and inspect the electronic devices for sale there. You’ll find economically priced televisions, stereos, VCRs, electric fans, microwave ovens and more, all bearing “Made In Korea” labels. And consider the immense success of Hyundai, the line of low-cost automobiles designed in Japan by Mitsubishi but built under license by Hyundai in Korea. Even though these cars are available only in certain areas of the U.S., more Hyundais were sold in their first nine months than any other foreign car has ever managed in its first full year.

Perhaps a like fate awaits a similar two-wheeled vehicle: the DH100, a lOOcc entry-level bike imported to the U.S. by TRAC, a company based in Atlanta, Georgia. Basically, the DH 100 is an overbored Honda S-90, circa 1960s, built in Korea by the Daelim Company under license from Honda in Japan. High-tech the DH100 is not, for mechanically, it’s virtually identical to that two-decades-old Honda 90, with contemporary bodywork.

But so what? Entry-level buyers couldn’t care less about cutting-edge technology. What’s important to them is price, reliability, and that they don’t feel intimidated by the bike’s size. At $799, with a weight of about 175 pounds and a solid, 20plus-year track record behind it, the DH 100 shouldn’t scare people away.

Of course, the major concern about Korean imports is the same as with those from Japan: Will they endanger American companies—and American jobs? In some cases, that’s a legitimate worry, but not with motorcycles. Harley-Davidson, the only American manufacturer, hasn’t been interested in entry-level bikes for decades; and since the Japanese either can’t or won’t market little bikes here, the efforts of TRAC—or any comparable outfit —in the U.S. should not be detrimental to their goals. To the contrary, anyone who can successfully market entry-level tiddlers will only help the motorcycle industry in this country simply by drawing more people into the sportmany of whom will eventually move up to larger, Japaneseor Americanbuilt bikes.

If that happens, no one loses. Instead, everyone wins. —Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

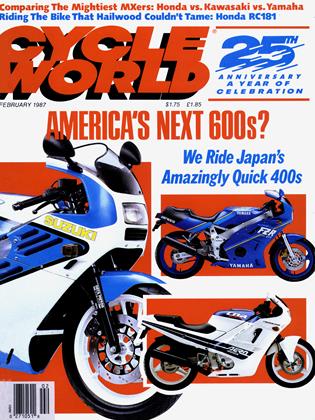

February 1987 -

Departments

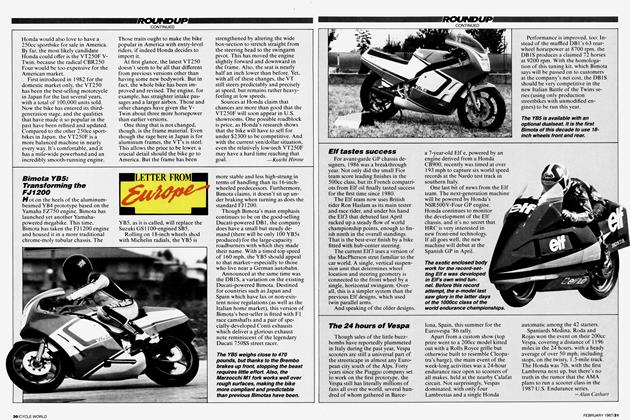

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

February 1987 -

Roundup

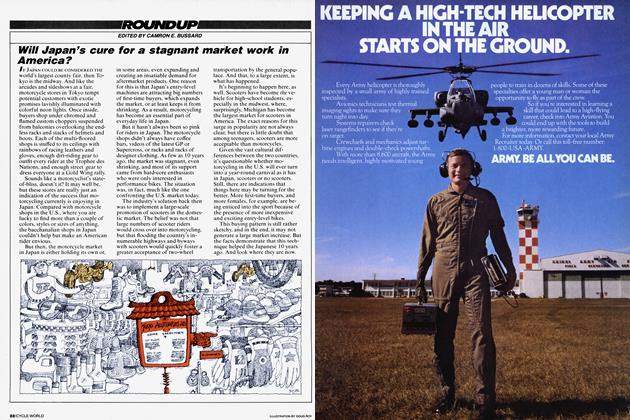

RoundupWill Japan's Cure For A Stagnant Market Work In America?

February 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupWhen School Is Meant To Be A Drag

February 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Entry-Level Sportbike: Destined For America?

February 1987 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupBimota Yb5: Transforming the Fj1200

February 1987 By Alan Cathart