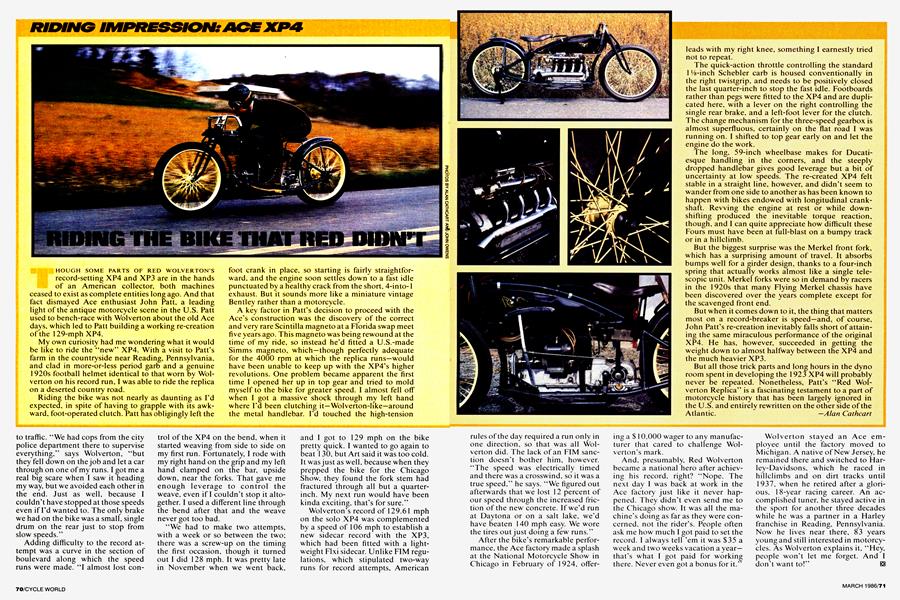

RIDING THE BIKE THAT RED DID'T

RIDING IMPRESSION:ACE XP4

THOUGH SOME PARTS OF RED WOLVERTONS record-setting XP4 and XP3 are in the hands of an American collector, both machines ceased to exist as complete entities long ago. And that fact dismayed Ace enthusiast John Patt, a leading light of the antique motorcycle scene in the U.S. Patt used to bench-race with Wolverton about the old Ace days, which led to Patt building a working re-creation of the 129-mph XP4.

My own curiosity had me wondering what it would be like to ride the “new” XP4. With a visit to Patt’s farm in the countryside near Reading, Pennsylvania, and clad in more-or-less period garb and a genuine 1920s football helmet identical to that worn by Wolverton on his record run, I was able to ride the replica on a deserted country road.

Riding the bike was not nearly as daunting as I’d expected, in spite of having to grapple with its awkward, foot-operated clutch. Patt has obligingly left the

foot crank in place, so starting is fairly straightforward, and the engine soon settles down to a fast idle punctuated by a healthy crack from the short, 4-into-l exhaust. But it sounds more like a miniature vintage Bentley rather than a motorcycle.

A key factor in Patt’s decision to proceed with the Ace's construction was the discovery of the correct and very rare Scintilla magneto at a Florida swap meet five years ago. This magneto was being rewound at the time of my ride, so instead he’d fitted a U.S.-made Simms magneto, which—though perfectly adequate for the 4000 rpm at which the replica runs—would have been unable to keep up with the XP4’s higher revolutions. One problem became apparent the first time I opened her up in top gear and tried to mold myself to the bike for greater speed. I almost fell off when I got a massive shock through my left hand where I’d been clutching it—Wolverton-like—around the metal handlebar. I’d touched the high-tension leads with my right knee, something I earnestly tried not to repeat.

The quick-action throttle controlling the standard 1 ‘/8-inch Schebler carb is housed conventionally in the right twistgrip, and needs to be positively closed the last quarter-inch to stop the fast idle. Footboards rather than pegs were fitted to the XP4 and are duplicated here, with a lever on the right controlling the single rear brake, and a left-foot lever for the clutch. The change mechanism for the three-speed gearbox is almost superfluous, certainly on the flat road I was running on. I shifted to top gear early on and let the engine do the work.

The long, 59-inch wheelbase makes for Ducatiesque handling in the corners, and the steeply dropped handlebar gives good leverage but a bit of uncertainty at low speeds. The re-created XP4 felt stable in a straight line, however, and didn’t seem to wander from one side to another as has been known to happen with bikes endowed with longitudinal crankshaft. Revving the engine at rest or while downshifting produced the inevitable torque reaction, though, and I can quite appreciate how difficult these Fours must have been at full-blast on a bumpy track or in a hillclimb.

But the biggest surprise was the Merkel front fork, which has a surprising amount of travel. It absorbs bumps well for a girder design, thanks to a four-inch spring that actually works almost like a single telescopic unit. Merkel forks were so in demand by racers in the 1920s that many Flying Merkel chassis have been discovered over the years complete except for the scavenged front end.

But when it comes down to it, the thing that matters most on a record-breaker is speed—and, of course, John Patt’s re-creation inevitably falls short of attaining the same miraculous performance of the original XP4. He has, however, succeeded in getting the weight down to almost halfway between the XP4 and the much heavier XP3.

But all those trick parts and long hours in the dyno room spent in developing the 1923 XP4 will probably never be repeated. Nonetheless, Patt’s “Red Wolverton Replica” is a fascinating testament to a part of motorcycle history that has been largely ignored in the U.S. and entirely rewritten on the other side of the Atlantic. Alan Cathcart

View Full Issue

View Full Issue