Back to square one?

EDITORIAL

I HEAR IT ALL THE TIME, SO I ASSUME that many of you do, too: Motorcycling in America has come a long, long way since the Japanese first entered into it more than 25 years ago. But has it, really? Back in 1960, just before the Japanese got involved, there were more brands of motorcycles for sale in this country than a person could keep track of. Nevertheless, the number of bikes sold annually was quite small by modern standards, and the market was dominated by a handful of manufacturers who specialized in big bikes—specifically, Harley-Davidson and a few European marques. There was a sizable number of small motorcycles available, but most were too crude and unreliable to be taken seriously, and few had much appeal to rank beginners. What little promotion given these small-bore bikes usually was in enthusiast magazines, precisely where their target audiencenon-riders—would not see it.

Unable, then, to attract significant numbers of new riders, motorcycling was not enjoying much growth. And the fact that the public thought of motorcycle riding as an outlaw activ ity didn't help matters.

Then, along came the Japanese, wiser in the art of building and mar keting small bikes than most people anticipated. Almost overnight, they created an entirely new image for mo torcycling, an image of everyday peo ple-doctors, nurses, students, house wives, clean-cut boy-next-door types-having fun on low-cost, non intimidating, socially responsible lit tle motorbikes. Not compulsive hot rodders terrorizing the local burger stands, not social misfits skulking around in dark, damp alleys in the middle of the night, but nice people with huge smiles on their faces hav ing the times of their lives on little SOs and 90s. And the Japanese didn't deliver this message just in bike mag azines, but, through television, radio and printed matter, they also sent it into every home in the country.

The rest is history. Americans re sponded in record numbers, and the great motorcycle boom of the Sixties was underway.

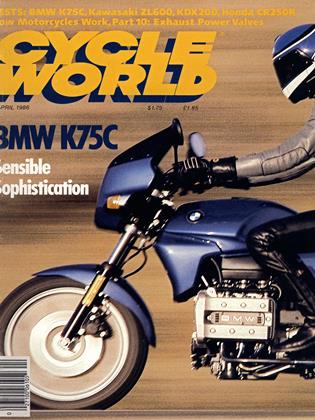

But the Japanese didn't stop at just creating one new motorcycle market; they also began opening up other new markets and servicing those that already existed. They steadily and progressively built bigger, better, more diversified motorcycles until they had models for practically every conceivable type of riding.

In the process. they also spent pro gressively less time and money de signing and marketing small, inex pensive motorcycles. Before long, they were concentrating most of their effort on making the biggest. fastest, most-sophisticated machines in the world, while all but forgetting about little bikes.

This has put us. in many critical ways, right back where we were 25 years ago. Sales volumes are way down in a market dominated by a few manufacturers who put almost all of their efforts into big, expensive mo torcycles. There are very few smaller bikes, and no minimal-cost "little" motorcycles like those that spurred the boom of the Sixties. So motorcycling once again is not

growing. partly because the absence of very small, inexpensive bikes is strangling it at its very roots. Today. "entry-level" models are bikes such as Honda's 250 Rebel, which, at $1500, is not cheap in the same way that Honda's $195 step-through 50 was cheap in 1 963. Neither is the 330-pound Rebel truly a small ma chine, especially when you consider that the "big bikes" of the Sixtiesthe 500cc and 650cc British Twins that were much too intimidating for beginners-weighed only 350 to 400 pounds. So although the Rebel has sold nicely since its introduction last year, it's still not likely to put the masses on two wheels the way those

Mopeds and scooters aren't the answer, either. They might have two wheels, but much of their popularity stems from the fact that they're really not motorcycles. So even though they sell in fairly large numbers, mostly to first-time riders, not many of their owners trade up to a motorcycle.

The manufacturers are not inter ested in little bikes, they claim, be cause the public isn't. They point out that they have included such ma chines in their lineups in recent times, but those bikes didn't sell.

True. But a key reason why they didn't is in the way they've been han dled: inexpensively. With rare excep tion, little motorcycles haven't been the subjects of massive ad campaigns like those back in the Sixties; they haven't been promoted in a way that has given non-riders an almost un controllable urge to run out and buy one. Instead, little bikes have just been along for the ride, mere hitch hikers on the big-bike bandwagon.

That approa~h will neverCwork. The Japanese built their empire on a solid foundation of little motorcycles that could lure just about anyone onto two wheels: but after expanding into just about every imaginable nook and cranny of the sport, they have moved off of that foundation. And because Japanese expansion has forced most other manufacturers out of this market, there's no one left who can build the little bikes needed to nurture future generations of big bike riders. Indeed, quite a lot of to day's enthusiasts, the people who ride the likes of Ninjas and Aspen cades and Viragos, started out on some little tiddler.

I don't know the exact solution to this dilemma, but logic suggests that the Japanese need to renew their commitment to really small, truly in expensive motorcycles. Not a bunch of Rebel-clones, but honest-to-god entry-level bikes-50s, lOOs, 125s.

Now, I'm not suggesting that the Japanese lift their entire 1 960s mar keting strategy and drop it down into 1986. Nor am I saying that they ought to revive the famous "You meet the nicest people on a Honda" ad campaign of that era.

On the other hand, I'm not saying that they shouldn't do so, either. Lis ten, the motorcycle business cer tainly could do a lot worse. Matter of fact, right now it is. -Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

At LargeThe Ultimate Vee

April 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupLatest Ninja Offspring

April 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupThe Black Queen

April 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesHigh In the Thin, Cold Air

April 1986 By Koji Hiroe -

Features

FeaturesSafety Frist

April 1986 By David Edwards