The Race Team That Wasn't There

RACE WATCH

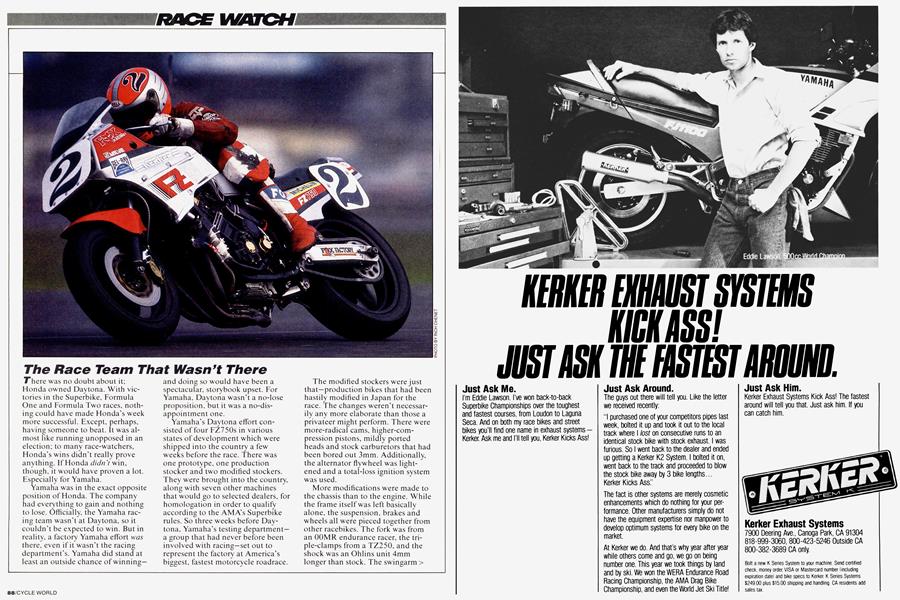

There was no doubt about it; Honda owned Daytona. With victories in the Superbike, Formula One and Formula Two races, nothing could have made Honda’s week more successful. Except, perhaps, having someone to beat. It was almost like running unopposed in an election; to many race-watchers, Honda’s wins didn't really prove anything. If Honda didn't win, though, it would have proven a lot. Especially for Yamaha.

Yamaha was in the exact opposite position of Honda. The company had everything to gain and nothing to lose. Officially, the Yamaha racing team wasn’t at Daytona, so it couldn't be expected to win. But in reality, a factory Yamaha effort was there, even if it wasn't the racing department’s. Yamaha did stand at least an outside chance of winning— and doing so would have been a spectacular, storybook upset. For Yamaha, Daytona wasn’t a no-lose proposition, but it was a no-disappointment one.

Yamaha’s Daytona effort consisted of four FZ750s in various states of development which were shipped into the country a few weeks before the race. There was one prototype, one production stocker and two modified Stockers. They were brought into the country, along with seven other machines that would go to selected dealers, for homologation in order to qualify according to the AMA’s Superbike rules. So three weeks before Daytona, Yamaha’s testing department— a group that had never before been involved with racing—set out to represent the factory at America's biggest, fastest motorcycle roadrace. The modified Stockers were just that—production bikes that had been hastily modified in Japan for the race. The changes weren’t necessarily any more elaborate than those a privateer might perform. There were more-radical cams, higher-compression pistons, mildly ported heads and stock carburetors that had been bored out 3mm. Additionally, the alternator flywheel was lightened and a total-loss ignition system was used.

More modifications were made to the chassis than to the engine. While the frame itself was left basically alone, the suspension, brakes and wheels all were pieced together from other racebikes. The fork was from an OOMR endurance racer, the triple-clamps from a TZ250, and the shock was an Ohlins unit 4mm longer than stock. The swingarm > was strengthened, and Brembo discs were used along with Dymag wheels.

CONTINUED

Selection of the riders was the hardest part. If Eddie Lawson were used it would elevate the level of the effort—suddenly people would expect Yamaha to win. Instead,

Wayne Rainey and Sam McDonald agreed to ride the two modified FZs.

The first obstacle appeared on the first day of tire testing when Rainey dropped one of the machines. The bike was only mildly bent, but Rainey broke his collarbone.

Rueben McMurter was signed on to ride the repaired FZ.

At Daytona the FZs were fast enough—they clocked a top speed of 161 mph, which is close to what the works Hondas turned. But in the infield the FZs lacked low-end and acceleration out of the turns. So McMurter and McDonald qualified well, but not on the front row.

The rest is a matter of record. The 200 was, as expected, a Honda showcase, with only two riders ever in front—privateer Wes Cooley and superhero Freddie Spencer. The first non-Honda was McMurter back in fifth place, on his crashed and restraightened FZ. McDonald had clutch troubles and didn't finish.

So as impressive as Yamaha’s lastminute, non-race-team, non-worksbike performance was, the company was denied a storybook upset.

Honda still won and Yamaha didn't.

But then, that won’t break any hearts at Yamaha. In fact, as far as Yamaha is concerned, it doesn’t really prove anything. Honda had to win. And Yamaha didn’t.

War News From The Africa Corps

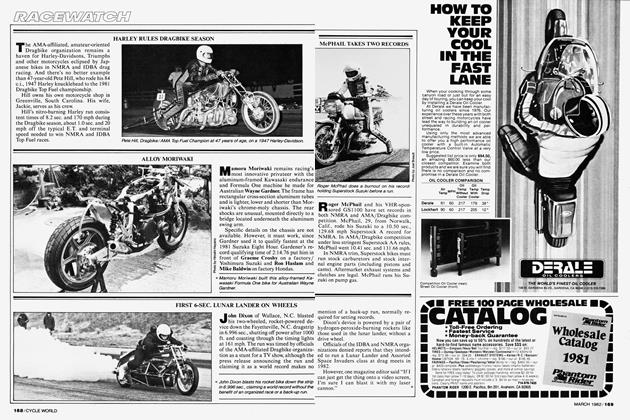

#f you were to draw any conclusion about the upcoming season of 500cc > GP roadracing based on the first round in South Africa, it would be that Eddie Lawson is making good on his promises. After winning the world championship last year, Lawson said, “I got that out of the way. Now I can race to win races.”

CONTINUED

That's exactly what Lawson did in South Africa. Honda’s Lreddie Spencer developed an early lead and set what would stand as the fastest lap time of the day. But the track temperatures were high, and Spencer had already competed in a previous race that day on his 250—a race that he had won easily. Spencer slowed his pace ever so slightly, and Lawson pushed his Yamaha through traffic to pass his long-time rival.

That Lawson is capable of outriding Spencer surprises few. That he did might be attributed either to his tires (he just switched from Dunlops to Michelins, just like those Lreddie uses) or to his bike (which Yamaha’s Kenny Clark terms as “faster and lighter”).

But more than likely, Lawson simply has something to prove.

The Comeback That Came Back

Ên motocross, the best riders don’t remain the best riders very long. By the time you've been around long enough to make it to the top, you’re usually too old to stay there.

Bob Hannah is the exception. Nine years ago, back in 1976—an eternity in motocross time—he was on top. He was AMA Rookie of the Year and 125cc national champion. Since then, Hannah’s career has had more peaks and valleys than the > Himalayas, but one thing has remained constant: He always is uncontested as the crowd’s favorite.

CONTINUED

At the start of his 10th—and possibly last—season as a professional motocrosser, Hannah has set out to give the crowds something to cheer about. At the first 250 national in Gainesville, Florida, Hannah put in a come-from-behind ride to grab second place. And the very next week at the Daytona Supercross, Hannah gave the fans what they really wanted with an overall win.

There have been other Hurricane warnings in the past, when it seemed like Hannah was on the comeback trail. But this comeback undoubtedly means more than the others—because it just might be his last.

RACE WATCH CALENDAR

Championship Events

CONTINUED

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

At Large

At LargeInside the Accidental Fortress

June 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

Rounup

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

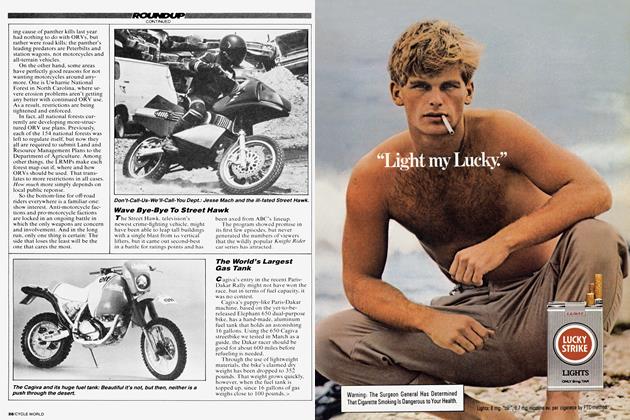

Roundup

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985