ONE LAP OF EARTH

RICHARD

MOPSA ENGLISH

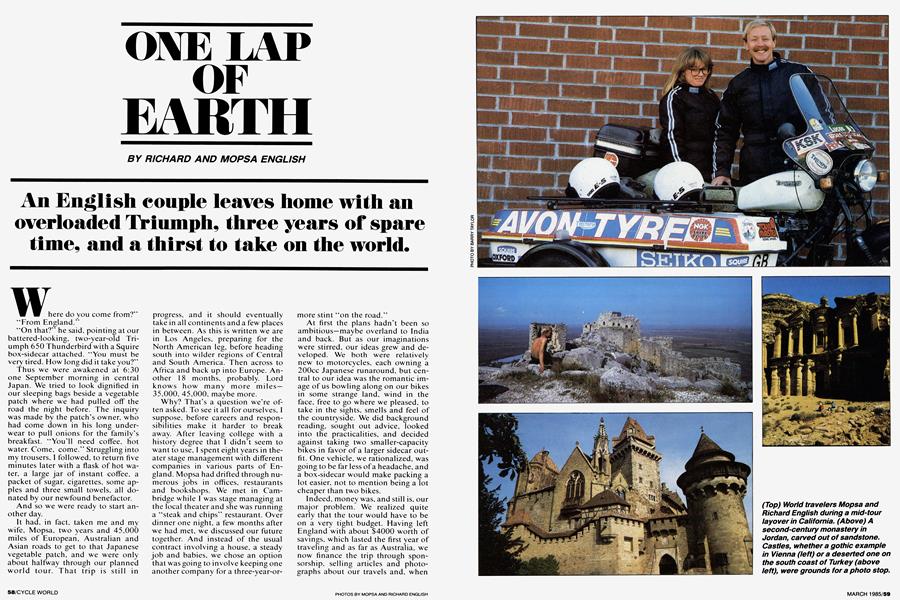

An English couple leaves home with an overloaded Triumph, three years of spare time, and a thirst to take on the world.

Where do you come from?" "From England."

“On that?” he said, pointing at our battered-looking, two-year-old Triumph 650 Thunderbird with a Squire box-sidecar attached. “You must be very tired. How long did it take you?”

Thus we were awakened at 6:30 one September morning in central Japan. We tried to look dignified in our sleeping bags beside a vegetable patch where we had pulled off the road the night before. The inquiry was made by the patch's owner, who had come down in his long underwear to pull onions for the family’s breakfast. “You’ll need coffee, hot water. Come, come.” Struggling into my trousers, I followed, to return five minutes later with a flask of hot water, a large jar of instant coffee, a packet of sugar, cigarettes, some apples and three small towels, all donated by our newfound benefactor.

And so we were ready to start another day.

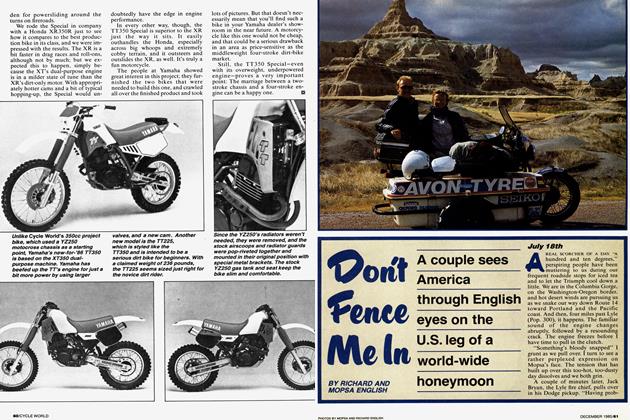

It had, in fact, taken me and my wife, Mopsa, two years and 45,000 miles of European, Australian and Asian roads to get to that Japanese vegetable patch, and we were only about halfway through our planned world tour. That trip is still in progress, and it should eventually take in all continents and a few places in between. As this is written we are in Los Angeles, preparing for the North American leg, before heading south into wilder regions of Central and South America. Then across to Africa and back up into Europe. Another 18 months, probably. Lord knows how many more miles — 35,000, 45,000, maybe more.

Why? That’s a question we're often asked. To see it all for ourselves, I suppose, before careers and responsibilities make it harder to break away. After leaving college with a history degree that I didn’t seem to want to use, I spent eight years in theater stage management with different companies in various parts of England. Mopsa had drifted through numerous jobs in offices, restaurants and bookshops. We met in Cambridge while I was stage managing at the local theater and she was running a “steak and chips” restaurant. Over dinner one night, a few months after we had met, we discussed our future together. And instead of the usual contract involving a house, a steady job and babies, we chose an option that was going to involve keeping one another company for a three-year-ormore stint “on the road.”

At first the plans hadn’t been so ambitious—maybe overland to India and back. But as our imaginations were stirred, our ideas grew and developed. We both were relatively new to motorcycles, each owning a 200cc Japanese runaround, but central to our idea was the romantic image of us bowling along on our bikes in some strange land, wind in the face, free to go where we pleased, to take in the sights, smells and feel of the countryside. We did background reading, sought out advice, looked into the practicalities, and decided against taking two smaller-capacity bikes in favor of a larger sidecar outfit. One vehicle, we rationalized, was going to be far less of a headache, and a box-sidecar would make packing a lot easier, not to mention being a lot cheaper than two bikes.

Indeed, money was, and still is, our major problem. We realized quite early that the tour would have to be on a very tight budget. Having left England with about $4000 worth of savings, which lasted the first year of traveling and as far as Australia, we now finance the trip through sponsorship, selling articles and photographs about our travels and, when necessary, getting off the bike and taking up casual employment.

From deciding to do the tour to actually leaving took us two full years: Money was saved, contacts made and information gathered on precisely what we might be letting ourselves in for. We tried for sponsorship and got some material help from several British motorcycle accessory and camping gear manufacturers. Triumph prepared the motorcycle for us, and we fitted a leading-link front fork and the box-sidecar. The car was severely overloaded with camping gear, tools, spare parts, all-weather clothes and a first-aid kit we felt would see us through plague, pestilence and all manner of broken limbs (but so far we’ve used only a couple of BandAids and some aspirin). We then set off through the last green weeks of a European summer in search of . . . what? The world? Ourselves? Maybe just adventure.

We both knew Europe pretty well, so we lingered there just long enough to come to grips with the realities of long-distance touring while still in a familiar environment, realities that included camping out in all types of weather; cooking edible meals in only one pot; getting to know the Triumph and the routine maintenance it would require; discovering what was less than essential in the excessive weight of our luggage, and sending it home. We also spent a good portion of our time just grinning at each other and saying, “Well, we’re actually doing it. Wow!’’

“I buy Missis English. She have good time. I plenty money, you sell . . . good price . . . just one day.” A grizzly, toothless Turk was looking Mopsa over appreciatively. A retired sailor who had learned his English in ports around the world, he looked not a day over 90, and little knew that the “Missis English” he wanted to buy from me was indeed Mrs. English. I wasn't selling. We were in Istanbul, a colorful, milling city with one foot in Europe and the other in Asia, and it was a pleasant relief after the dour austerity of the Easternblock countries. As we wandered through the city we were astonished to see many sheep and goats being slaughtered and hung up for skinning. We had unwittingly arrived on the first day of the Eidh al Adaha, a major Moslem festival. We later discovered that it was traditional on this day for the rich to give meat to those less well off.

We had been warned that the roads would be hazardous in Turkey, that young kids would lie in wait to throw stones at passing tourist vehicles, that thieves and trickery would abound. These warnings were without foundation. The roads, although far from perfect, were being gradually upgraded, and the people we met were friendly and hospitable. We spent a leisurely month meandering around the Aegean and Mediterranean coastlines, enjoying the changes in scenery, the multitude of ancient ruins and the strange and wonderful natural phenomena: eroded rock formations, the pink and sandy earth of the Konya plateau, the magnificent calcified waterfalls of Pamukkale.

From Turkey we had a choice of routes to Pakistan: either through Iran, or by turning south through Syria and Jordan, across Saudi Arabia and then by boat from one of the many ports along the southern side of the Arabian Gulf. The Iranian entry procedures seemed at that point to change from day to day, so, since we had friends to visit along the other route, southward we turned.

Our arrival at the Syrian border, however, was almost enough to make us question our decision. There were several offices to get authorization from, for ourselves and for the bike, and although the individual offices were clearly marked, all the signs were in Arabic. The offices were spread randomly over more than an acre, none of the officials spoke English, and all of them had a tendency to ignore any appeal addressed to them in a foreign tongue. So we did as we’d been advised and hired the services of a “hustler,” who, for a small fee, took all our documents in hand and sped through the procedures, jumping lines here and slipping a little “baksheesh” there. He got us through in less than three hours amid scenes of frustrated long-distance truck drivers arguing at the tops of their voices and paperwork being waved wildly in the air.

Once into Syria, the greenery of the landscape gave way to scrub and desert. Because the country is politically unstable and almost permanently in a state of war, we were frequently stopped both by civilian armed militia and by the army. Two foreigners on an odd-looking motorcycle outfit were bound to arouse suspicion. But once they had checked us out (usually at gunpoint), traditional Moslem hospitality prevailed, and we were marched off, still at gunpoint, to drink tea or share a meal before being sent on our way.

It was also in Syria where we crossed our first desert—a straight and lonely road with only sparse brush and a few wandering herds of goats to break the line of the horizon. The desert ran to Palmyra, a centuries-old oasis city that in Greek and Roman times had controlled, and thrived on, the trade links to the Persian gulf ports that fed the East. Jordan, too, had some interesting roads, one of which, following the Dead Sea Basin, descends to the lowest point on Earth, close by the Israeli border, where we rode through the warm air that hangs heavy over the desolation. The traditional King’s Highway runs along the high plateau overlooking this same Dead Sea Basin, with landscape to match the Grand Canyon, and so very, very little traffic to intrude upon your solitude.

Once we had left Europe, the standard of driving had steadily deteriorated as we headed east. In the Moslem countries, the old saying “might is right” certainly applies to traffic behavior. Accidents are attributed to the will of Allah—an excuse for all kinds of reckless driving. Speeding trucks would practically force us off the road, but the drivers would invite us to share tea and food if we later met them farther along the way.

Saudi Arabia is very difficult for non-Moslems to visit, so we were able to get only a 72-hour visa to ride the 1200 miles across the flat, northern Saudi desert to the gulf state of Qatar. Fortunately, it was wintertime and not too hot; the summer temperatures here can rise to well over 120 degrees. We relieved the endless monotony of the road that follows the Trans-Arabian pipeline by counting the wrecked cars that had been driven off the road by wealthy, careless drivers and simply left, half-buried in the drifting sands, to disintegrate. They averaged one per kilometer! It seems that the Saudis, with their newfound oil wealth, have given up their traditional camels for the greater comfort of large, air-conditioned American cars. And on several occasions, we were amused to see camels being transported in the back of pickup trucks.

Having chosen the southern route over the vagaries of Iran, we had to ship the bike from Dubai to Karachi in Pakistan. Here we met a perfect example of one of the major headaches of taking a motorcycle across international borders: unnecessary and time-consuming paperwork. It took three full days to process the bike through customs, going from one office to another, from the port to the city center, to collect signature and counter-signature on all manner of forms and papers. This was despite all our documents being 100 percent in order and up-to-date. It was bureaucracy at its worst, and it only worked at all if we handed over several small bribes to keep our papers at the the top of the pile.

Karachi was also an excellent introduction to what driving in Asian cities was going to be like. Against all odds, they somehow manage to function amid chaotic carousels of cars and trucks, buses and taxis, camel and ox carts, wandering cows and goats, bicycles and small motorcycles, rickshaws and people. Whenever and wherever we stopped, we immediately were surrounded by groups of curious people who prodded and kicked the tires, pulled at the turn signals and talked excitedly—to us and amongst themselves—while beggars tugged at our sleeves and traffic generally ground to a halt all around. The only way to escape was to rev the engine and edge carefully through. The bike was the center of attention, and often, out of these crowds came an invitation to drink tea. Or something more fortifying.

In Europe and the Middle East we had generally camped out at nights, setting up our small tent next to the outfit, either in campsites or by the side of the road, and cooking meals over our small, gasoline-pressure stove. In Pakistan and India this was less than easy, privacy and security both being hard to find. Consequently, because hotel accomodations and restaurant food are so very cheap there (although a bit basic), we usually chose these softer options. Many hotels and lodging houses had night watchmen, but they would usually sleep on the job; so managers often insisted that we drive the outfit up precariously balanced planks of wood into a foyer or courtyard where it would be safer. Sometimes they underestimated the weight of our vehicle, and we shattered many a plank. Our sidebox was always well padlocked and all our gear securely stored inside, but we still usually hired some young boy or storekeeper to watch over it for a very small fee when we wanted to explore on foot. Indeed, at one popular temple we were hard-put to avoid a fistfight between the many lads who all wanted to watch over the outfit for us.

From Karachi we continued north, working our way up into the foothills of the Himalayas. Our plan had been to take the road up to the Kunjerab Pass, toward the border with China, but heavy snows completely blocked our path. Instead, we turned west to attempt the Khyber Pass as far the the Afghan border. But the Pakistani government doesn’t really control the tribal areas through which the road to the pass runs, and the local Pathans, fiercely independent, were unhappy about certain recent government actions in the region, so no permits to travel this route were being issued. We decided to try anyway, and got as far as Jamrud Fort—the gateway to the Khyber—where we were soon surrounded by wild-looking tribesmen, wrapped in blankets and draped with bandoliers, each one carrying a rifle. They closely inspected the bike, gave us cups of the local green tea, and after hanging their guns around Mopsa, posed with her while I took photographs. But they allowed us no further.

There is only one road-crossing open between Pakistan and India, that being between Lahore and Amritsar, so our first introduction to India was the city that houses the very beautiful headquarters of the Sikh religion—the Golden Amritsar Temple. Although the atmosphere was a little tense due to recent militant activity, there was no hint of the terrible violence that was soon to break out and eventually lead to the assassination of Indira Gandhi.

Nothing can really prepare you for India. It is exhausting to travel through, particularly on a motorcycle, since you are so very open to the environment, and the experience can be very demanding. We found it important not to attempt to drive too far, lest all our energies be expended just getting from A to B. We spent four months touring the country, from the mountains of Kashmir in the north to the western state of Rajasthan, down the tropical west coast to Bombay and Goa, across the southern state of Karnataka and into drought-ridden Tamil Nadu. Those four months on the Indian roads only allowed us to cover probably a third of the country, and even then we barely scratched its surface.

India is, however, covered by a wide network of roads, although they are at times a little rutted and uneven. Since the roads have unlimited access, they’re filled with a confusion of vehicles and people and activities: slow-moving ox or bullock carts; white-clad men wobbling on ancient bicycles; rows of graceful, sari-clad women balancing clay or brass water jars on their heads; stinking diesel trucks; and all manner of buses, ranging from high-speed, air-conditioned tourist buses to rickety, rusty ones filled to overflowing with passengers hanging from the doors and clinging to the roofracks.

All of this requires undivided attention and constant braking. In one small south Indian town, we almost ran over a naked Saddhu, or holy ascetic, as he rolled toward us in the middle of the dusty road. We assumed he had decided to roll around the roads of India as a demonstration of his great religious faith. And because cattle are sacred in India, they’re allowed to roam at will and have right of way over everything; invariably, they wandered directly into our path, unconcerned by the howling of horns and squealing of brakes.

Outside of Delhi and Bombay we could only find gas of a very low octane, so we were glad that we had lowered the compression of the Triumph in anticipation of this. Motorcycle workshops can be pretty basic, but the mechanics seem to know their trade and are accustomed to adapting and making up unavailable parts. When we overheated in Turkey and broke a piston ring, we soon found a workshop in which to re-hone the barrel, before returning to the campsite to fit the one spare piston we were carrying. That piston took us 14,000 miles, to Australia.

And what Australia is, to us, is a hot, dry wind full in the face. A roasting engine between the legs. Flat, flat land. Unchanging scenery. An endless, straight road, with tire rubber almost peeling off on the rough, burning asphalt. The eyes begin to close. Falling asleep again. No. shake the head. Something shimmers on the road ahead. Shake the head and concentrate. It’s almost certainly a tractor-trailer that will buffet us and shower us with grit and sand. First vehicle for over an hour.

We’d come to Australia by container ship from Sri Lanka, where we had narrowly avoided the violent rioting that had engulfed that small island of up-country tea estates, lowlying rubber plantations, golden beaches and Buddhist stupas. We had left Australia’s northeastern seaboard and were heading south through the interior of Queensland, riding much faster than our usual 45 miles per hour, intent on covering distance as quickly as possible. Not so comfortable riding this flat, dry, hot country. Stops in small townships and at isolated roadhouses for a cold drink or a beer. Flies clustered on our arms and backs, moving slowly, like the people. Deserted and dusty streets, an air of the forgotten. Quick dips in murky waterholes to cool off. So very different from the tourismoriented coast and the cosmopolitan city of Sydney, where we had arrived two months earlier.

The severe conditions during the last few days in the sun-baked outback of Australia had us envisaging the engine of the Triumph burning up beneath us, so we found and fitted an oil cooler. We then rode, rode, rode, first west, then north toward Darwin, holding our breath as we passed the bloated carcasses of cattle that lay stinking by the the road.

To the outsider, Australia gives an impression of vast uniformity of language, customs and scenery. How wrong. Australia is like not one country but three, perhaps four or five. Coming from England, we found it a fascinating combination of the alien and the familiar. Sometimes we felt like pioneers as we braved the harshness of the outback, only to be brought back to reality by Aussie humor. Idling away the interminable hours on the highway down to Alice Springs, we tried to imagine how it might have been for the white explorers who first charted this barren land, for the men who constructed the overland telegraph line. Simple markers by the side of the road were modest reminders of their endeavors. We stopped at one, in the fierce midday heat, close to Central Mount Stuart, the geographical center of the continent, only to find that the plaque had been removed, and in its place had been carefully lettered the plaintive question, “Which way to the beach?"

Heading out to Ayers Rock at dusk we were treated to a double-sided electrical storm, the centers of which were on either side of the road, with lightning arcing across above us. What an entry. Then south and off the tarmac, down the infamous corrugated dirt road toward Coober Pedy, before turning left to ride 700 miles down the very isolated Oodnadatta Track. The sidecar fittings couldn't cope with the constant vibrations caused by the never-ending corrugations, and three times we had to stop to readjust them after riding the outfit at impossible angles. We limped into Adelaide, the engine drinking oil in one cylinder, and had to replace worn valves and guides.

Our four-month, 12,000-mile circular trip of Australia, over roads that wouldn’t have us pass a handful of vehicles in the course of a full day’s riding, had certainly tested the motorcycle, not to mention ourselves. But oh, the sky and the vast horizon; the wonder of that very special Australian light; the untouched tropical rain forests of north Queensland; the red, red earth of the central region; the golden barley fields of the south. It’s a country where the landscape gets into the soul.

What a contrast, then, to find ourselves back in Asia. After a brief visit to Bali and Java without the outfit, we flew into Singapore to collect our motorcycle from the port area. We slowly made our way up the Malaysian Peninsula to Bangkok, through rubber plantations and dense jungle, stopping a few days at a typical, coconut-lined beach where each night, giant leather-backed turtles would wade ashore to lay and bury their eggs in the sand. We continued through buzzing fishing villages until we came into the noise, bustle, fumes and frantic pace of Bangkok.

Despite the beauty of that city’s palaces and temples, we were glad to escape the traffic and head north through Thailand’s small towns and rice-growing countryside. We rode up to the famed Golden Triangle, where Thailand, Burma and Laos meet, and gazed across the Mekong river to those two inaccessible countries. Then, while monsoon clouds gathered and the first rains began to fall, we turned and headed back. First, though, we slipped and slid the motorcycle over some sodden dirt roads, covering ourselves in mud. to visit some of the more remote hilltribe villages in the area. After that, a full week of torrential rain accompanied us, drenched and exhausted, back to Singapore, where we put the bike on a boat to Yokohama, Japan.

Next came a month in the vast metropolis of Tokyo, battling with single-minded commuters on subways and crossings, where the oppressive humidity of the summer had us wilting and listless. Maneuvering a sidecar around the Tokyo streets required infinite patience; congestion was extreme, and it literally took hours to get across town. We yearned for the open road, but that’s something very hard to find in Japan. Our first ride out of the capital was to Osaka and Kyoto; and. forbidden by law to ride “two-up” on the expressways (which in any case have prohibitive tolls), it took us nearly two days to cover 400-odd miles through the continuous built-up area that stretches from Tokyo along the coast.

It was quite a relief, then, to finally head north for Hokkaido to enjoy the mountain roads and passes, camping by volcanic lakes or on pebbly river beds, and breathing in the late summer air. During three months in Japan, we only managed four and a half thousand miles, and didn’t get to everywhere we’d planned. But despite the traffic problems, it's a country where there are temples and shrines to delight the eye, landscape to uplift you, and a culture so alien to our own, with such mystifying codes of behavior, that one could spend many times longer there and still be fascinated. And a kinder people, more eager to help and guide tourists through the complexities of the country, you couldn't hope to meet.

And now. after more than two years riding the roads of Europe, Australia and Asia, we are indeed a little tired, if not exhausted. But more often we've been excited, exhilarated and educated. Our strange, ungainlylooking motorcycle and sidecar have been crucial to this, making friends for us where we least expected to find them, as well as carrying us and our belongings across deserts, through forests, over mountains, from country to country, continent to continent on our crazy quest to experience the world from the road.

With 18 more months of traveling ahead of us. we look forward to much, much more of the same.

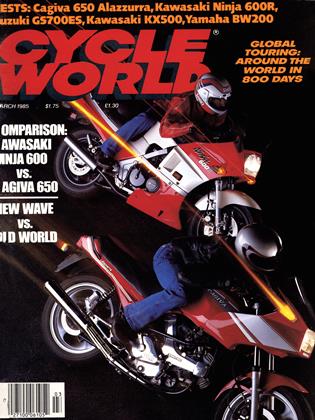

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Matter of Opinion

March 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1985 -

Departments

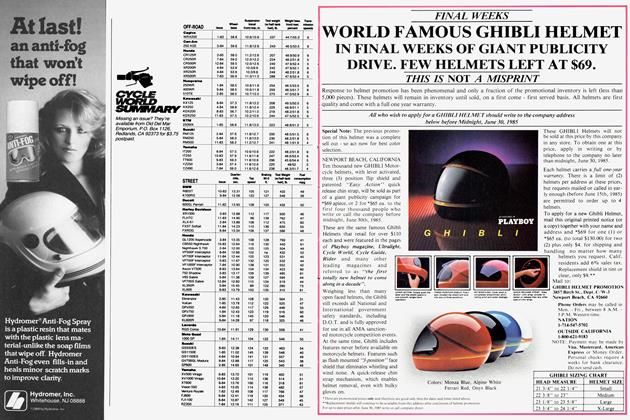

DepartmentsSummary

March 1985 -

Roundup

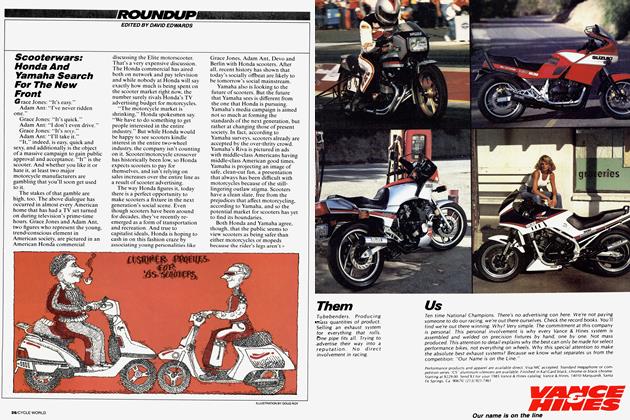

RoundupScooterwars: Honda And Yamaha Search For the New Front

March 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupThe $590 Million Engine Rebuild

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThree-Wheeling, British-Style

March 1985