SUZUKI SP600

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A PLAYBIKE THAT TAKES FREEDOM SERIOUSLY

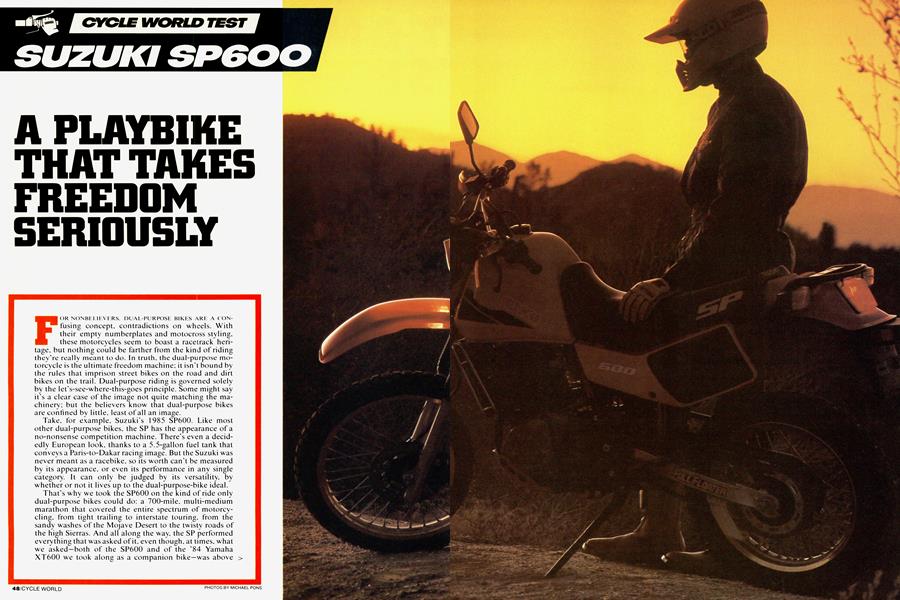

FOR NONBELIEVERS. DUAL-PURPOSE BIKES ARE A CONfusing concept. contradictions on wheels. With their empty numberplates and motocross styling, these motorcycles seem to boast a racetrack heritage, but nothing could be farther from the kind of riding they're really meant to do. In truth, the dual-purpose motorcycle is the ultimate freedom machine it isn't bound by the rules that imprison street bikes on the road and dirt bikes on the trail. Dual-purpose riding is governed solely by the let's-see-where-this-goes principle. Some might say it's a clear case of the image not quite matching the machinery; but the believers know that dual-purpose bikes are confined by little, least of all an image.

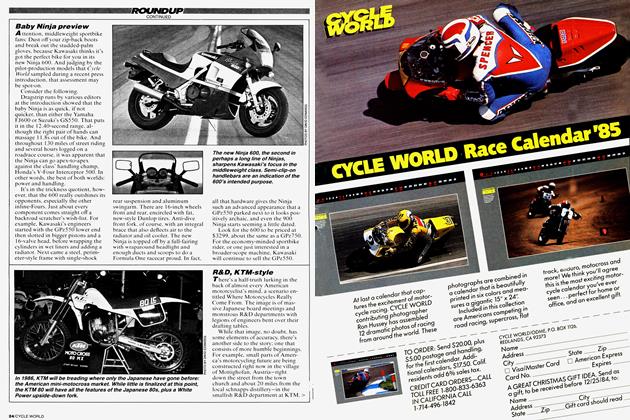

Take, for e~arnple, Suzuki's 1985 P6OO. Like most other dual-purpose bikes, the SP has the appearance of a no-nonsense competition machine. There's even a decid edly European look, thanks to a 5.5-gallon fuel tank that conveys a Paris-to-Dakar racing image. But the Suzuki was never meant as a racebike, so its worth can't be measured by its appearance, or even its performance in any single category. It can only be judged by its versatility, by whether or not it lives up to the dual-purpose-bike ideal.

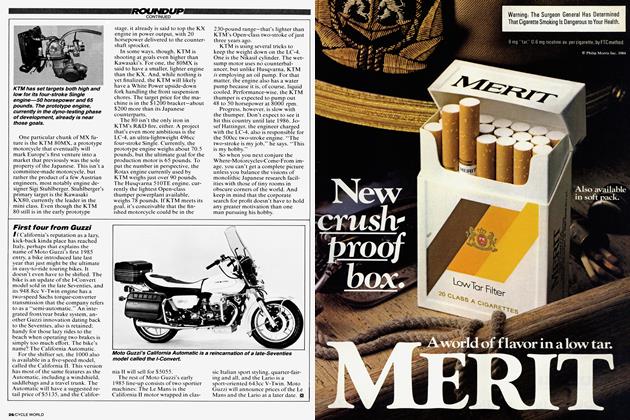

That's why we took tleSP600 on t'bei~dnd of ride only dual-purpose bikes could do: a 700-mile, multi-medium marathon that covered the entire spectrum of motorcy cling, from tight trailing to interstate touring, from the sandy washes of the Mojave Desert to the twisty roads of the high Sierras. And all along the way, the SP performed everything that was asked of it. even though. at times, what we asked-both of the SP600 and of the `84 Yamaha XT600 we took along as a companion bike-was above and beyond the call of dual-purpose duty.

"OTHER DUAL PURPOSE BIKES ARE FASTER AND LIIHTER, AND THAT ALONE WILL BE ENOUGH TO MAKE THE FACT-WATCHERS CONDEMN THE SPGOO AS HOPELESSLY MEDIOCRE. BUT THEY'LL BE WRONG."

Som~e of the most gruelin~ t~rrain en~ountered on the ride was in the high desert, where they grow whoop-de doos the size of small buildings. That kind of terrain defi nitely is more than any street-legal motorcycle bargains for. But with gaps of empty space between its tires and fenders rivaling those seen on any motocrosser, the SP600 promises to take its dirt riding seriously.

That's no empty promise, ther. On~moderately choppy ground, the SP never jumps or hops, and even on rougher trails, both ends of the bike work amazingly well. The surprising part is that even though the SP looks like it has as much travel as the average works motocrosser, it actu ally has only 9.4 inches in the rear and 8.9 in the front. That makes the suspension all the more impressive, con sidering Suzuki was able to make the bike fee/ like it has more travel.

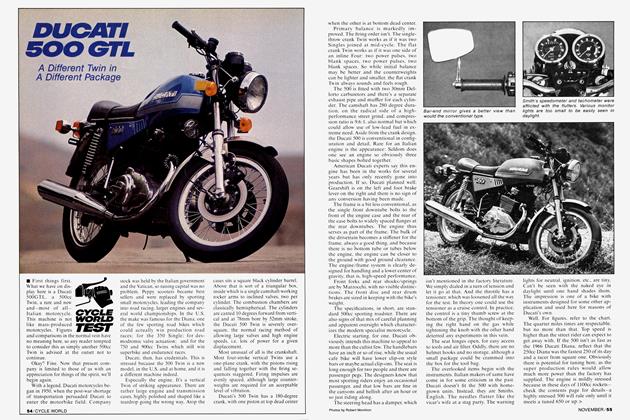

In part. some of that feel might be present because the SP600 is the first Open-class dual-purpose Suzuki to use the Full Floater single-shock rear suspension system. In fact, this is the first Open-class dual-purpose bike Suzuki has even offered in two years. The previous model was the `83 SP500, which was little-changed from the `82 model, and both had twin shocks and not very much travel, front or rear. The 5P600 uses a rear suspension system similar in concept to that used on the RM motocrossers, although in actual construction the two systems are quite different. The SP uses steel for the shock body, linkage and swingarm. and has no external adjustments for compres sion or rebound damping.

On the other hand, the SP does have a spring preload adjuster that is far easier to use than any that has ever appeared on an RM. Rather than the brute-force, ham mer-and-punch tuning techniques required by most other off-road and dual-purpose bikes, adjusting the SP's pre load is dead-simple: Just turn a 12mm hex-head adjuster on the left side of the shock body, which, in turn, rotates a five-position adjuster cam atop the spring. For most of our multi-terrain ride we left the spring preload on the center position, which made for a good compromise.

Of course, the SP's rear si~spension~does have its limita tions. As you might expect, when you subject the machine to either extreme-casual around-town riding or the afore mentioned killer whoops-it seems slightly out of place. When the bike hits sharp pavement irregularities at low speeds. the suspension sometimes seems harsh, even on the softest preload setting. Also, the longish (by pure streetbike standards) wheel travel makes the machine feel tall and awkward; for short riders, the ground seems fright eningly far away. That's compounded by the wide seat, which aids the SP's comfort on long trips, but also makes it hard for almost ani' rider to touch the ground flatfooted.

Off the road, the bigger bumps and whoops likewise are beyond the SP's range. generally causing the bike to get sideways easily and become a challenge to control. But that kind of terrain is beyond the scope of any dual-pur pose bike: and compared with the other machines in its class, the SP's front and rear suspension is truly outstanding.

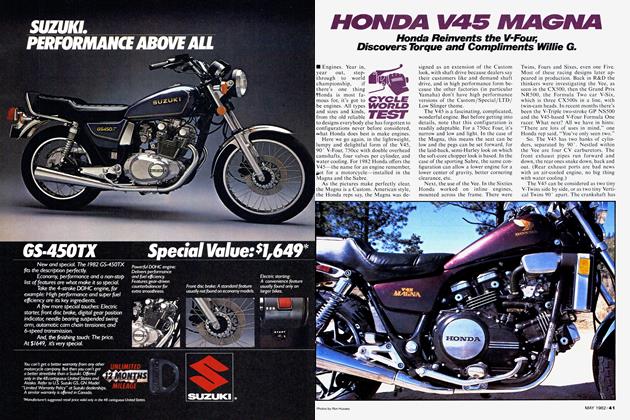

By those same standards, though, the SP weighs in on the heavy side. At 322 pounds dry, the Suzuki is about 1 5 to 20 pounds heavier than any other 600, aside from Ka wasaki's liquid-cooled KL600R. But even though Yamaha's XT600 is lighter and physically smaller, the SP is much more agile, onand off-road. The Suzuki steers with surprising ease, and on a flat, winding trail, the only time you're conscious of the machine's bulk is at very low speeds. Above 20 mph, the SP goes where it's pointed without the wrestling match required to turn the XT.

Actually, the only'~time the SP might feel less agile than the XT-or, for that matter, most other dual-purpose mo torcycles-is when the Suzuki's tank is full. Then, the SP feels awkward at almost any speed. And it's no wonder: The tank holds 5.5 gallons, which equates to about 270 miles of range per tankful. But it also means that when the tank is full, there are more than 33 additional pounds positioned at virtually the highest point on the machine. Even when the tank is only half-full, you sometimes can feel a distinct weight-shift as the bike is leaned and all the gas splashes to one side of the tank.

Tl~at's a relatively small but valid complaint, and so is another: The SF600 could be more powerful. Both the Honda XL600R and Yamaha XT600, `84 models, of course, will pull away in any gear, at any speed. Again, though, seven-G acceleration isn't a requisite for having fun on a dual-purpose bike. And though the SP has a slight horsepower handicap. it has a very broad, satisfying powerband and downright civilized engine manners. Compared to the Yamaha, the SF is smoother, quieter, easier to start, harder to stall, and much cleaner-running, even in the worst conditions. During our torture trek, we rode the two bikes at altitudes ranging from sea level to over 6000 feet. And at no time did the big SP's heart skip a beat. The Yamaha, on the other hand, had a built-in altim eter: The higher we traveled, the worse it ran.

That sur~ised us, because the SP uses a single. 40mm Mikuni carburetor instead of a twin-carb set-up such as found on the Honda and Yamaha. High-tech carburetion systems like the Honda's and the Yamaha's might well give the Suzuki more power, but the SP's old-fashioned system is simple and reliable-and it works anywhere.

Actually, the Suzuki is devoid of almost any elaborate engine trickery, unless you still care to label a four-valve head as trick. The engine is loosely based on the old wetsump SP500 powerplant, the most important difference being the new model's 6mm larger bore and 3mm longer stroke. That opened the SP up to 589cc, and created the need for a beefier rod, larger bearings, and upsized parts throughout the engine. The motor still uses a single, gear driven counterbalancer, which does a very effective job of smoothing the big thumper's vibrations. The Suzuki vi brates far less than the Yamaha, but it's not as smooth as the Kawasaki, KL600R, which uses two separate counterbalancers. - - - -

Aside from those displacement-oriented changes. the only other significant differences between the SP500 and 600 engines are the 600's dual-sparkplug head and twin header pipes. And, as with almost every other big thumper, the SP now uses an automatic compression release to make starting easier. The mechanism partially opens one ex haust valve when the kickstart lever is depressed the first few inches. It's possible to bypass the release by using only the last half of the kickstarter's stroke; but we never had any trouble with the system and, in fact, the engine usually started on the first kick. The SP also has a handlebar mounted, manual compression-release lever, an item that the Yamaha and Kawasaki both sorely need.

Don't get the idea, however, that the Suzuki is free of bothersome attributes. If the SP's owner decides to strip the machine of unnecessary weight, for instance, he'll find that the nonessentials are difficult to remove. The luggage rack is great for long trips, but you should be able to re move it if you don't need it. Not possible-at least not without also losing the rear-fender mounts and the rear blinkers. Same goes for the rear-fender extension. It's re quired in some parts of Europe but not here, and if you ash-can it, you also throw away your license-plate light and holder. And even if you don't care about keeping the bike street-legal. removing the SP600's headlight and in struments is overly complicated.

There were oth~r aspercts of the SP that annoyed us more and more as we became intimate with the machine in the course of our ride-a-thon. The grips, we found, are too narrow for anyone with a hand wider than ET's, particu larly when wearing any sort of cold-weather gloves. And it's hard to tell if the push-button kill switch is off or on, a fun little tidbit to discover after 20 unsuccessful kicks. In all fairness, though, it's always more difficult to note the positive details, simply because they aren't annoying. Details like the handguards, which protect the rider's hands from brush and cold wind: the smooth, positive way the transmission shifts gears: the strong, reliable front disc brake and drum rear brake: and the 0-ring chain, which stands up to incredible abuse. - --

Little things like that can make the difference between just any motorcycle and aftiii motorcycle. And the SP600 unquestionably is a fun motorcycle. But for some, the SP will just be another middle-of-the-road motorcycle be cause it excels in no single category. Other dual-purpose bikes are faster and lighter, and that alone will be enough to make the fact-watchers condemn the SP600 as hope lessly mediocre.

But they'll be wrong. Because, while the Suzuki isn't excellent at anything, it's very good at everything. That means the SP600 scores high marks when the standard is versatility, which, in turn, means the bike also scores high in freedom. For dual-purpose motorcycles, that's the high est standard of all.

.WITH GAPS OF EMPTY SPACE BETWEEN ITS TIRES AND FENDERS RIVALING THOSE SEEN ON ANY MOTOCROSSER, THE SP PROMISES TO TAKE ITS DIRT RIDING SERIOUSLY'

SUZUKI SP600

$2399

U.S. Suzuki Motor Corp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue