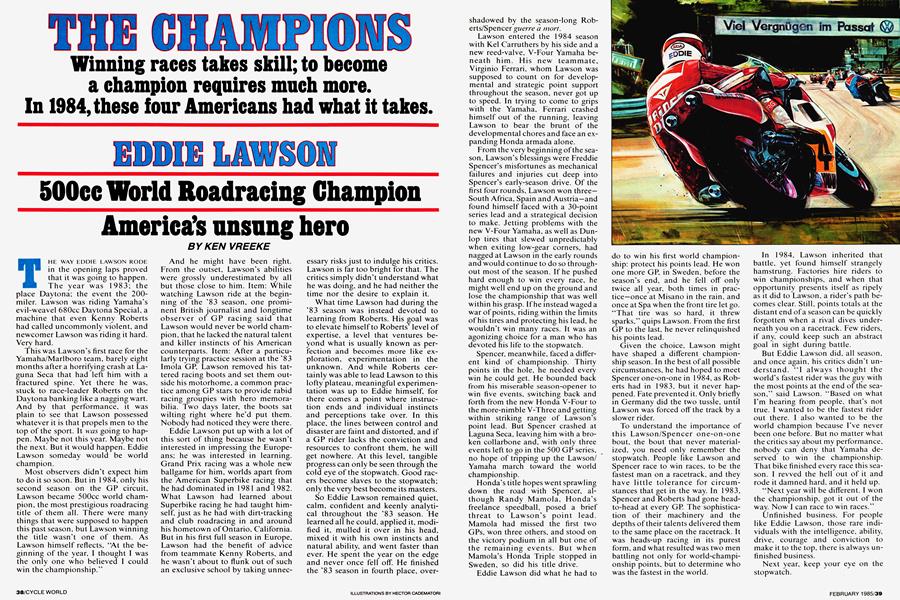

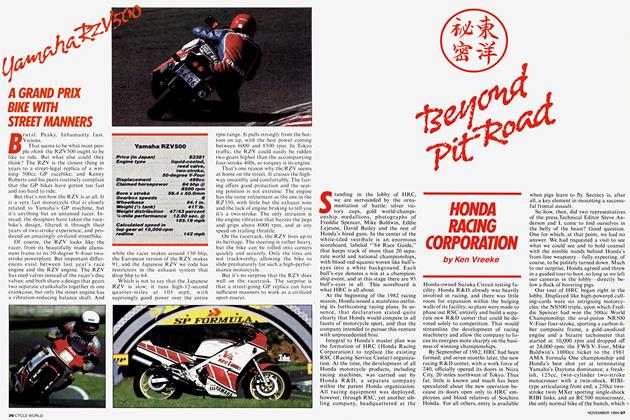

EDDIE LAWSON

THE CHAMPIONS

500cc World Roadracing Champion

America's unsung hero

Winning races takes skill; to become a champion requires much more. In 1984, these four Americans had what it takes.

KEN VREEKE

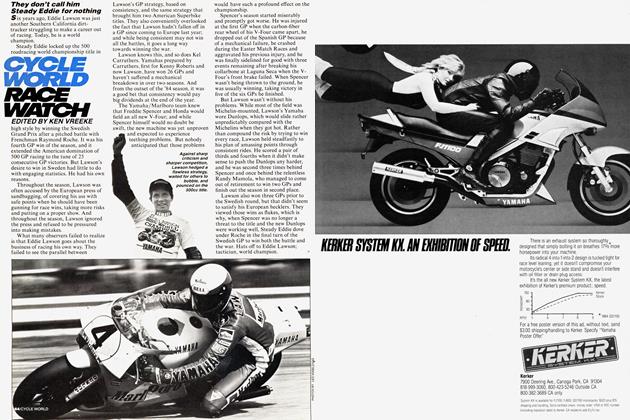

THE WAY EDDIE LAWSON RODE in the opening laps proved that it was going to happen. The year was 1983; the place Daytona; the event the 200miler. Lawson was riding Yamaha's evil-weavel 680cc Daytona Special, a machine that even Kenny Roberts had called uncommonly violent, and newcomer Lawson was riding it hard. Very hard.

This was Lawson's first race for the Yamaha/Marlboro team, barely eight months after a horrifying crash at La guna Seca that had left him with a fractured spine. Yet there he was, stuck to race-leader Roberts on the Daytona banking like a nagging wart. And by that performance, it was plain to see that Lawson possessed whatever it is that propels men to the top of the sport. It was going to hap pen. Maybe not this year. Maybe not the next. But it would happen. Eddie Lawson someday would be world champion.

Most observers didn't expect him to do it so soon. But in 1984, only his second season on the GP circuit, Lawson became 500cc world cham pion, the most prestigious roadracing title of them all. There were many things that were supposed to happen this past season, but Lawson winning the title wasn't one of them. As Lawson himself reflects, "At the be ginning of the year. I thought I was the only one who believed I could win the championship."

And he might have been right. From the outset, Lawson's abilities were grossly underestimated by all but those close to him. Item: While watching Lawson ride at the begin ning of the `83 season, one promi nent British journalist and longtime observer of GP racing said that Lawson would never be world cham pion, that he lacked the natural talent and killer instincts of his American counterparts. Item: After a particu larly trying practice session at the `83 Imola GP, Lawson removed his tat tered racing boots and set them out side his motorhome, a common prac tice among GP stars to provide rabid racing groupies with hero memora bilia. Two days later, the boots sat wilting right where he'd put them. Nobody had noticed they were there.

Eddi~e Lawson put up~with a lot of this sort of thing because he wasn't interested in impressing the Europe ans; he was interested in learning. Grand Prix racing was a whole new bailgame for him, worlds apart from the American Superbike racing that he had dominated in 1981 and 1982. What Lawson had learned about Superbike racing he had taught him self, just as he had with dirt-tracking and club roadracing in and around his hometown of Ontario, California. But in his first full season in Europe, Lawson had the benefit of advice from teammate Kenny Roberts, and he wasn't about to flunk out of such an exclusive school by taking unnec essary risks just to indulge his critics. Lawson is far too bright for that. The critics simply didn't understand what he was doing, and he had neither the time nor the desire to explain it.

What time Lawson had during the `83 season was instead devoted to learning from Roberts. His goal was to elevate himself to Roberts' level of expertise, a level that ventures be yond what is usually known as per fection and becomes more like ex ploration, experimentation in the unknown. And while Roberts cer tainly was able to lead Lawson to this lofty plateau, meaningful experimen tation was up to Eddie himself, for there comes a point where instruc tion ends and individual instincts and perceptions take over. In this place, the lines between control and disaster are faint and distorted, and if a GP rider lacks the conviction and resources to confront them, he will get nowhere. At this level, tangible progress can only be seen through the cold eye of the stopwatch. Good rac ers become slaves to the stopwatch; only the very best become its masters.

So Eddie Lawson remained quiet, calm, confident and keenly analyti cal throughout the `83 season. He learned all he could, applied it, modi fied it, mulled it over in his head, mixed it with his own instincts and natural ability, and went faster than ever. He spent the year on the edge and never once fell off. He finished the. `83 season in fourth place, overshadowed by the season-long Rob erts/Spencer guerre a mon.

Lawson ei~'tered the 1984 season with Kel Carruthers by his side and a new reed-valve, V-Four Yamaha be neath him. His new teammate, Virginio Ferrari, whom Lawson was supposed to count on for develop mental and strategic point support throughout the season, never got up to speed. In trying to come to grips with the Yamaha, Ferrari crashed himself out of the running, leaving Lawson to bear the brunt of the developmental chores and face an ex panding Honda armada alone.

F Fron~'the very beginning of the sea son, Lawson's blessings were Freddie Spencet's misfortunes as mechanical failures and injuries cut deep into Spencer's early-season drive. Of the first four rounds, Lawson won threeSouth Africa, Spain and Austria-and found himself faced with a 30-point series lead and a strategical decision to make. Jetting problems with the new V-Four Yamaha, as well as Dun lop tires that slewed unpredictably when exiting low-gear corners, had nagged at Lawson in the early rounds and would continue to do so through out most of the season. If he pushed hard enough to win every race, he might well end up on the ground and lose the championship that was well within his grasp. If he instead waged a war of points, riding within the limits of his tires and protecting his lead, he wouldn't win many races. It was an agonizing choice for a man who has devoted his life to the stopwatch.

Spencer, meanwhile, faced a differ ent kind of championship. Thirty points in the hole, he needed every win he could get. He bounded back from his miserable season-opener to win five events, switching back and forth from the new Honda V-Four to the more-nimble V-Three and getting within striking range of Lawson's point lead. But Spencer crashed at Laguna Seca, leaving him with a bro ken collarbone and, with only three events left to go in the 500 GP series, no hope of tripping up the Lawson! Yamaha march toward the world championship.

Honda's title hopes went sprawling down the road with Spencer, a! though Randy Mamola, Honda's freelance speedball, posed a brief threat to Lawson's point lead. Mamola had missed the first two GPs, won three others, and stood on the victory podium in all but one of the remaining events. But when Mamola's Honda Triple stopped in Sweden, so did his title drive.

Eddie Lawson did what he had to do to win his first world champion ship: protect his points lead. He won one more GP, in Sweden, before the season's end, and he fell off only twice all year, both times in prac tice-once at Misano in the rain, and once at Spa when the front tire let go. "That tire was so hard, it threw sparks," quips Lawson. From the first GP to the last, he never relinquished his points lead. -

diven the choice, Lawson might have shaped a different champion ship season. In the best of all possible circumstances, he had hoped to meet Spencer one-on-one in 1984, as Rob erts had in 1983, but it never hap pened. Fate prevented it. Only briefly in Germany did the two tussle, until Lawson was forced off the track by a slower rider.

To understand the importance of this Lawson/Spencer one-on-one bout, the bout that never material ized, you need only remember the stopwatch. People like Lawson and Spencer race to win races, to be the fastest man on a racetrack, and they have little tolerance for circum stances that get in the way. In 1983, Spencer and Roberts had gone headto-head at every GP. The sophistica tion of their machinery and the depths of their talents delivered them to the same place on the racetrack. It was heads-up racing in its purest form, and what resulted was two men battling not only for world-champi onship points, but to determine who was the fastest in the world.

In 1984, Lawson inherited that battle, yet found himself strangely hamstrung. Factories hire riders to win championships, and when that opportunity presents itself as ripely as it did to Lawson, a rider's path be comes clear. Still, points totals at the distant end of a season can be quickly forgotten when a rival dives under neath you on a racetrack. Few riders, if any, could keep such an abstract goal in sight during battle.

But Eddie Lawson did, all season, and once again, his critics didn't un derstand. "I always thought the world's fastest rider was the guy with the most points at the end of the sea son," said Lawson. "Based on what I'm hearing from people, that's not true. I wanted to be the fastest rider out there. I also wanted to be the world champion because I've never been one before. But no matter what the critics say about my performance, nobody can deny that Yamaha de served to win the championship. That bike finished every race this sea son. I revved the hell out of it and rode it damned hard, and it held up.

"Next year will be different. I won the championship, got it out of the way. Now I can race to win races."

Unfinished business. For people like Eddie Lawson, those rare indi viduals with the intelligence, ability, drive, courage and conviction to make it to the top, there is always un finished business.

Next year, keep your eye on the stopwatch.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue