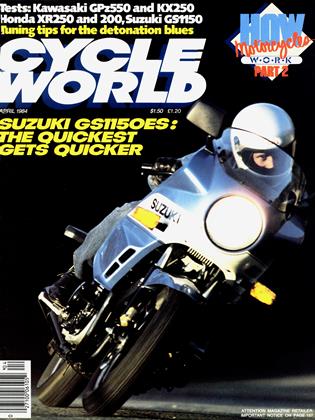

SUZUKI GR650: FOR 14,000 MILES, A GOOD AND FAITHFUL SERVANT.

LONG-TERM REPORT

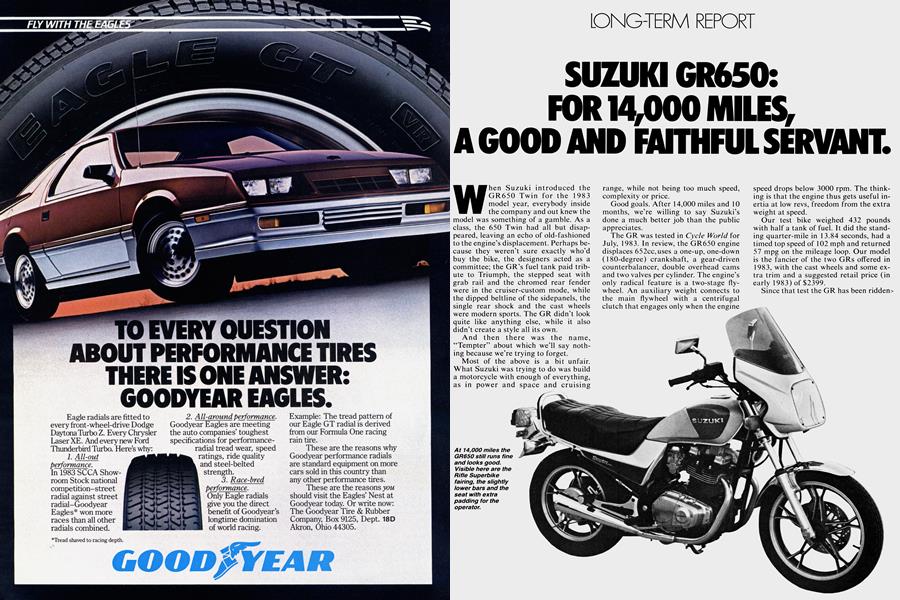

When Suzuki introduced the GR650 Twin for the 1983 model year, everybody inside the company and out knew the model was something of a gamble. As a class, the 650 Twin had all but disappeared, leaving an echo of old-fashioned to the engine’s displacement. Perhaps because they weren’t sure exactly who’d buy the bike, the designers acted as a committee; the GR’s fuel tank paid tribute to Triumph, the stepped seat with grab rail and the chromed rear fender were in the cruiser-custom mode, while the dipped beltline of the sidepanels, the single rear shock and the cast wheels were modern sports. The GR didn’t look quite like anything else, while it also didn’t create a style all its own.

And then there was the name, “Tempter” about which we’ll say nothing because we’re trying to forget.

Most of the above is a bit unfair. What Suzuki was trying to do was build a motorcycle with enough of everything, as in power and space and cruising range, while not being too much speed, complexity or price.

Good goals. After 14,000 miles and 10 months, we’re willing to say Suzuki’s done a much better job than the public appreciates.

The GR was tested in Cycle World for July, 1983. In review, the GR650 engine displaces 652cc,uses a one-up, one-down (180-degree) crankshaft, a gear-driven counterbalancer, double overhead cams and two valves per cylinder. The engine’s only radical feature is a two-stage flywheel. An auxiliary weight connects to the main flywheel with a centrifugal clutch that engages only when the engine speed drops below 3000 rpm. The thinking is that the engine thus gets useful inertia at low revs, freedom from the extra weight at speed.

Our test bike weighed 432 pounds with half a tank of fuel. It did the standing quarter-mile in 13.84 seconds, had a timed top speed of 102 mph and returned 57 mpg on the mileage loop. Our model is the fancier of the two GRs offered in 1983, with the cast wheels and some extra trim and a suggested retail price (in early 1983) of $2399.

Since that test the GR has been ridden in daily service, and for fun on weekends, and for several weekend trips. It's been remarkably reliable; never failed to start, never needed roadside service. There have been several minor bothers, one surprise and one major disappointment.

The Service Record

At 2000 miles, the tachometer cable disengaged from the drive unit on the cylinder head. The drive went with the cable and was never seen again. It and the cable were replaced from the dealer’s shelves, no further problem here.

The fuel petcock tightened up and flipping from On to Reserve became a struggle. But because it’s always been possible to do from the saddle, it's never been fixed.

Heavy hands on the taillight housing, which is chrome-plated plastic, produced a giant crack. The housing was lavishly wrapped in duct tape, which is still holding the thing together.

We became aggravated by the battery location. It’s under the seat between the tool tray and the air filter. Neither comes off easily and the battery level can’t be checked unless the cables are removed and the battery yanked into the open. So far our men have checked the level often enough to keep the battery in good health, but we wish it wasn’t that much work.

At 4000 miles oil began seeping from the front of the base gasket, and the rear, and from the end plugs on the cam covers. None of these leaks were major. The base gasket has been left as is; of cosmetic concern only. The cam covers have a reuseable neoprene gasket. We sealed the leaks first with Yamabond No. 4 (an excellent product, by the way) but the cure was only temporary.

At 4500 miles, the speedometer light went out, followed a few hundred miles later by the illumination for 5 in the gear selection window, and later the other numbers. Bulbs, we learned at a later service.

(Let the record show we had a 650 Twin with oil seeps and bulbs and things being shaken out, yet not one word have we said about those other Twins, leaks and vibration.)

Nevermind.

Right after that the chain guard lost a bolt, replaced by rooting around in the bin at a friendly Arizona gas station. Up to this point the GR has been giving mileage in the 55-60 mpg range, with the low of 45 coming on a fast cross-desert trip pushing a windshield, to be detailed later. Right after this we did a miracle gearing change, also following this section., and the mpg went to 60-65.

The worst shock, a terrible pun, as you’ll see, hit at 7000 miles. The GR was in the dealership for service and the seeping fluid on the swing arm and rear fender turned out to be oil from the shock. This is a single shock design, with ride height set via an oil canister, sort of like the reservoirs on motocross bikes. Ours had lost its seal. The shop manual said not to repair, but to return the shock to the U.S. headquarters and replace it. Which we did, this being covered by warranty. A freak failure, by Suzuki’s account, but not what we’ve come to expect.

The agency mechanic said if it was his, or if the warranty had expired and the owner agreed, he'd be tempted to try fixing the leak. If the bill had been ours, we’d have given permission for the experiment.

Another surprise at 7400 miles. The front brake pads were worn to the metal backing. They went that far, too far, because we’d never seen pads wear that quickly and weren’t looking.

The worn pads were replaced with pads from the dealer’s shelf, but not from Suzuki. Sorry, the package got lost. They cost $20, and are still on the machine with lots of material left. But. They aren’t as good in the rain as the production pads were. If half a warning is better than none, here it is: get the stock pads and check them often.

After that, virtually nothing is on the log for service and repair. The GR got oil changes by us at 3000 mile intervals, and full services at 7000 and 1 1,000 miles. At the second service, the cam cover gaskets were replaced and slathered with Yamabond and the covers have been clean since. The base gasket has oozed enough oil to convert grit into grunge, but that’s all.

An impressive 14,000 miles. At this writing, the head pipes have yellowed but the rest of the chrome is, well, chrome. The exhaust tips look rusty but are intact. The paint still takes polish well. The black finish on the engine has turned gray and defied our efforts to restore, but that’s something all black engines experience.

Everything mechanical is in top shape: the sealed O-ring chain needs adjustment every 10,000 miles, that is, virtually never. Nor does it show signs of wear. The clutch, shifter, levers, pedals, cables, etc. are like new.

This is a good, basic, strong machine. If the asking price has dropped faster than the sales curve has risen, well, blame the market but not the motorcycle.

Experiments

Parallel to the main task of trying to ride our long-term bikes into the ground, we also use them as rolling test beds.

The man to whom the GR was assigned didn’t like the bars, for instance. Too high. So the stock bars were swapped for lower ones. The new set came from a rack at the local Kawasaki/BMW/Moto Guzzi store. We think they’re early KZ650. The swap did mean removal of the lead weights fitted to the Suzuki bar ends, to dampen engine vibrations at the grips. We did notice a slight increase in buzz at the grips with the new bars, but nothing critical

continued on page 128

continued from page 114

The added tingle was removed from the bars by changing the stock grips for a pair of Ourys. They look like the more familiar Ourys seen in motocross, but longer. The wide waffle pattern is comfortable and the rubber-substitute doesn’t get slick in the rain. Good grips.

Our man wasn’t too happy with the stock seat, never mind that he’s never happy with any stock seat. He yanked the staples from the stock cover and added about an inch of foam to the front half, while trimming back the step to the second half. It was better. But then the GR went to the dealer’s for service and the dealer, who's an old friend, took it upon himself to fix what looked like an accident. He re-stapled the cover. Because the added padding was an improvement, and because anything further would have come under the heading of fiddling, the seat was never re-opened. If it’s useful to know, there’s room beneath the cover for some custom work

PBI Sprocket

If the stock GR650 has one flaw, it’s gearing. Perhaps because all the factories like good numbers from tests, or perhaps because people who.can build engines that will hold up to high revs don’t worry about how high the revs are, the GR comes with a 15-tooth countershaft sprocket and 38-tooth rear wheel sprocket. That’s a final drive ratio of 2.53:1 and gave an engine speed of 4640 rpm at 60 mph.

With this gearing the GR was at the same time underloaded and overstressed. At 70, the cruising speed most people use on the really open road, the engine felt unhappy, nearly out of breath. No damage, no threat, but noisy enough to give the rider a sense of guilt.

So we shopped around. PBI, Clackamas, Oregon, is a specialist in sprockets of all sizes, so we ordered a 17tooth front for the GR. Details in this month’s Service, for those who need to know.

There’s no picture of the sprocket here because it’s on the bike, that is, it’s too darned much trouble to get at.

Changing the sprocket requires removal of the sprocket cover, in turn requiring removal of the shift linkage. The sprocket is held on by a PAL-type nut. It’s self-locking to a degree that demands a long breaker and a heavy foot. Next, the front edge of the case guard must be ground back to provide clearance for the larger sprocket.

Then, vast improvement. The two added teeth change the final drive ratio to 2.23:1. Revs at 60 mph drop to 3600 rpm and at 4600 rpm, the old rev reading at 60, road speed is nearly 70. And the engine feels happier and makes less noise. The GR has enough low-end power, and enough of a spread between the gears, to easily pull away from a stop in 1st gear. Mileage has been in the low 60s ever since.

Last time we ran the GR against the clock it had a true timed speed of 97 mph, versus the 102 when new, geared lower. The GR won’t pull redline—at the engine’s limit of 8500 rpm, calculated top speed would be 110—so the taller gears make the engine less able to wind into the danger zone. This is all theory: those who wish to pile up points against their licenses can do so as easily with a 97-mph bike as with a 102-mph bike. In short, the gearing change is terrific, the best thing we did with the GR.

Slip Streamer Windshield

Because the GR650 is relatively small, we wanted to gain some weather and wind protection at reasonable cost, both in dollars and effort.

The first try was a Slip Streamer windshield, a clear plastic shield that attached to the handlebars and fork tubes. It seemed large for the bike, so we cut it down, to be told later by a reader who had the same shield that we could have mounted it lower and saved ourselves the work.

The Slip Streamer gave added weather protection, at a modest cost in mpg. We were a bit disappointed in the hardware, which broke after the GR was ridden on a dirt — but no motocross! — road. Still, at $109 th< windshield was a good deal.

Rifle Superbike Fairing

The Rifle Superbike fairing is a frame-mount fairing, with less frontal area and a sharper angle of attack, so to speak, than the windshield. It gave cleaner air around the rider’s head, less protection for hands and trunk. Because of the shape and size, the Rifle provided streamlining; the GR went faster with ii than without it. And this meant mor», miles per gallon, 65 in daily use to nearb 70 on the highway.

The Rifle also suffered broken hardware from dirt roads. Mr. Editor Girdle made a comment about this and preste the guys at Rifle called. The brackets i question had in fact proven to be w jr'than they should have been. New better material were in productio, set was enclosed, under warranty.

In the meantime, one of the busin staff rode the GR home and while it v parked beneath the garage door, his , shut the door. Or tried to. The fairu, was scraped and the hardware bent, but no permanent harm was done. This is a good fairing, even for $160, and it’s still on the bike.

Conti Super Twins

As soon as the regular test was tin ished, just shy of 3000 miles, the stock IRC tires were replaced with a set o; Continental Super Twins, the latest from that firm.

After some break-in, the tires were tested. The tires, mind. With the stock tires, braking distances were 36 feet from 30 mph, 141 from 60. Average. With the Contis, the distances were 27 and 114. Excellent. Superior.

We didn’t test for cornering power, nor for wet weather traction, although the tires seemed to work well on the road wet or dry.

After 11,000 miles the rear tire is showing some wear, the front looks aE new. Tire wear isn’t a constant, that is, a tire can go through its first half of life quicker than the second half. So we can’t definitely predict. But from the experience so far, the rear tire will be safe for 15,000 miles or so.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue