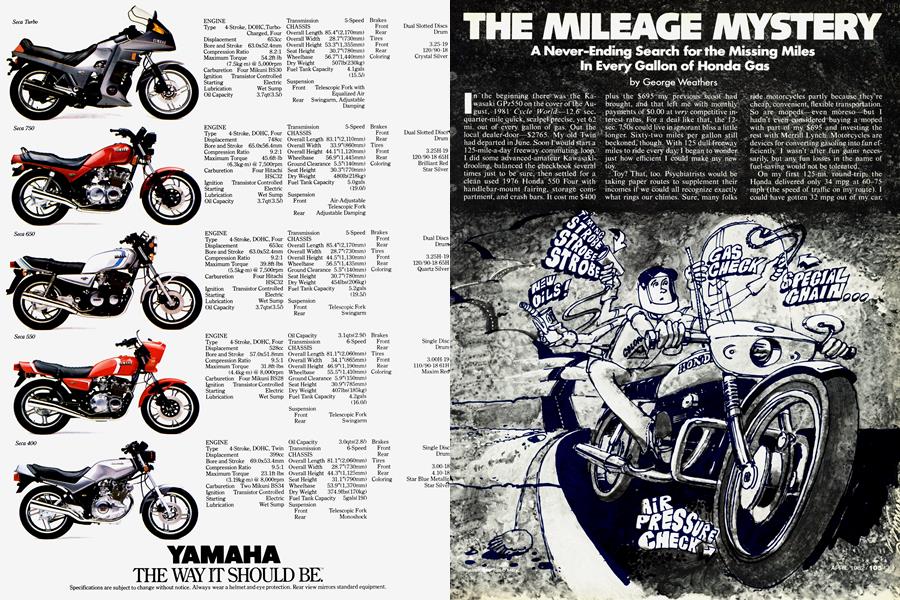

THE MILEAGE MYSTERY

A Never-Ending Search for the Missing Miles In Every Gallon of Honda Gas

George Weathers

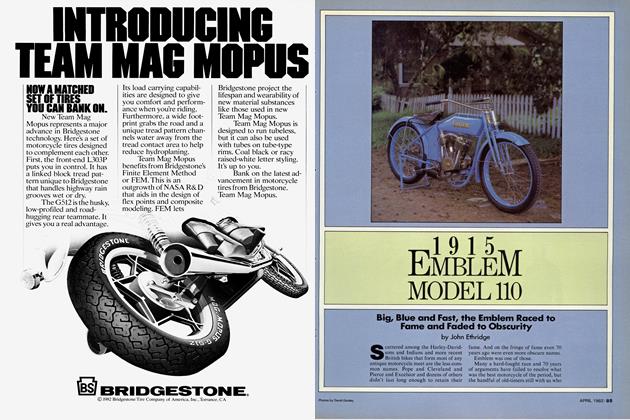

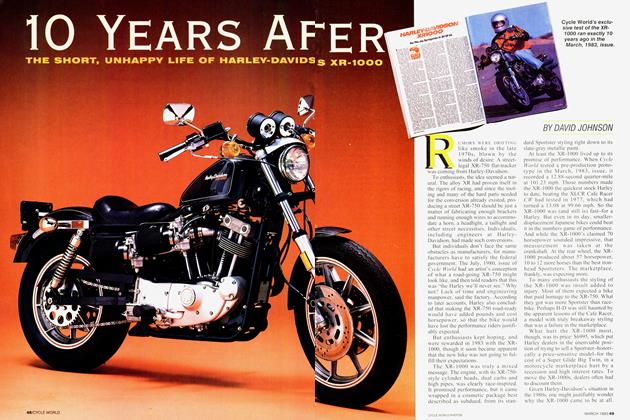

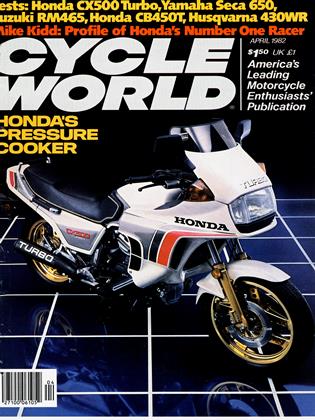

In the beginning there was the Kawasaki GPz550 on the cover of The August 1981 Cyc1e World—12.6 sec.

quarter-mile quick, scalpel precise, yet 62 mi. out of every gallon of gas Out the local dealer-door&$x2014;$2765. My old Twin nad departed in June. Soon I would start a 125-mile-a-day freeway commuting loop. I did some advanced-amateur Kawasakidrooling balanced the checkbook several times just to be sure, then settled for a clean used 1976 Honda 550 Four with handlebar-mount fairing, storage compartment, and crash bars. It cost me $400

plus the $695 my previous voot had brought and that left me with monthly payments of $0.00 at er~ competitive in terest rates. For a deal like that, the 12sec 7~Os could live in ignorant bliss a little longer Sixty two miles per gallon still beckoned though With 12S dull freeway miles to ride every day, I began to won4er just how efficient I could make my new toy.

Toy" That too Psychiatrists would be taking paper routes to supplement their incomes if we could. all recognize exactly what rings our chimes. Sure, many folks

rtde motorcycles partly because they re cheap, convenient, flexible transportation. So are mopeds--even moreso-but I hadn t even c~ns1dered buying a moped with part of my $695 and investing the rest with Merrill Lynch~ Motorcycles are devices for converting gasoline into fun ef ficiently 1 wasn t after fun gains r~eces saril~ but any fun losses in the name of fuel-saving would not be tolerated.

On my first 125 m~ round trip the Honda delivered only 34 mpg at 60-75 mph (the speed of traffic on my route). I could have gotten 32 mpg out of my car, though I wouldn’t have enjoyed the trip as much. The second day, I set my jaw, held on tight, and rode a saintly 55 mph the whole way. Efficiency climbed immediately—38 mpg, a 12 percent improvement. Fun vanished, replaced by terror. Think the double-nickel saves lives? At 55 I developed a severe case of Toyotasupposiphobia—the obsessive fear of having a small Japanese sedan driven deep into one’s tailpipe. Back to keeping up with traffic—and 34 mpg.

I tried to learn how far off its new-bike economy my Honda was. In August of 1976, Cycle magazine compared seven middleweights in a road-test shoot-out. Yamaha’s XS500C, the most economical of the bunch, recorded 42.2 mpg. Suzuki’s GT380 was thirstiest at 31.7 mpg. A Honda CB550F like mine registered 36.7 mpg brand new. These bikes all turned quarter miles in the 14 sec. range. In September of 1981, Cycle World magazine did a similar shoot-out with 750cc bikes. Quarter-mile times all fell near 12.5 seconds. But the thirstiest 750 in 1981 registered 45 mpg—better than the best 1976 middle weight! The stingiest 750 squeezed 55 miles out of every gallon.

Next I checked points, timing, plugs, tire pressure, and air cleaner. Though points and plugs looked almost new, I cleaned the air cleaner, lubed and adjusted the chain (an every-other-day ritual), and reset the timing with a strobe light. Tire pressure matched the specifications (28 psi), and plugs were burning chocolate-malt-brown and dry. All this got me 1 mpg more.

I’d heard from several sources that the stock Honda 550 air cleaner was awful. “Go K&N,” people said, “the big model they make for replacing the stocker or the four little cuties if you want to riehen jetting.” Not wanting to riehen jetting, I bought the big, under-the-seat filter— $21.35 for filter and special filter oil. The mileage jumped promptly from 35 mpg to 45 mpg—most dramatic gain of anything I tried. Spark plugs now were burning coffee-with-cream—about as slight a color as I wanted to risk on the street. At $1.25 a gallon for regular gas, that meant my filter would pay for itself once it had saved about 17.1 gallons—2672 mi. of riding. Major mileage gain, cheap part, 2672 mi. I considered that as I prowled the aisles of the motorcycle supermarts, pondering $150 electronic ignitions, $400 fairings, $250 exhaust headers. Plunk the big bucks down to buy more fun; how happy is your wallet? But in the absolute-efficiency game, bikes are too efficient already for most big investments to pay for themselves over the service life of most machines. Figures don’t lie—if figures appeal to you.

Next I looked at the fairing, the one that had come on the bike. One of those one-size-fits-all numbers, it graunched badly against the tach-speedometer of the 550. By the time the previous owner had gotten the headlight to shine out the proper hole, the windshield jutted forward. The whole ungainly arrangement was not quite as well-streamlined as a ’65 Ford van in reverse. I pitched the fairing in the garage. Mileage promptly jumped to 47 mpg, but wind noise on the highway reminded me of standing outside in a hurricane, not to mention grasshoppers in the T-shirt at 60. I could guess how much worse it would all have been without a helmet. Cut-and-try brackets finally relocated fairing and headlight to where things were every bit as well streamlined as the back end of a Ford van. Mileage settled in at 46 mpg—better than any Ford van in reverse.

Fiaving gone from Twin to Four, I was really starting to enjoy my 125 mi. commute. These middleweight Fours, even an older one like mine, have it all—performance better than anything with more than two wheels, reasonable weight, precise handling, turbine smoothness, yet here I was paying less than 3-cents a mile for gas. The preceeding sentence, of course, is highly opinionated. There are many people who would only be happy getting 125 mpg or more on some tiny tiddler (people immune to Toyotasupposiphobia, obviously), or getting 11-sec. acceleration when they turn the loud handle (pathological Toyotasupposiphobiacs), or feeling the throb of a Fat Bob Harley between their legs (Japanese go home). There may be people who actually like riding on a commuter bus (though they probably aren’t reading this). Takes all kinds.

I began a long series of flirtations with Miracle Goop: gasolines, oils, and additives promising improved mileage. I sometimes think Fve seen Miracle Goop work (though I don't believe Fve ever seen Sasquatch). With my Honda though, nothing helped at all and a couple things hurt. No lasting damage—the service manual warned about using those honey-looking friction-reducers in bikes with wet clutches running in engine oil. I did try a short fling with graphite-additive oil, but it cost me 1 mpg which I gained back with my return to plain ol’ 10w40. A friend of mine swore by 5w20 synthetic oil in his Yamathree, and thinner oil should certainly take less energy to circulate, but I was riding through mid-90° temperatures and didn’t try thin oil.

I also tried a tank of national brand gas. Fd been using the cheapest stuff I could buy en route, but if 5 cents/gal. more expense would deliver more than 4 percent better economy (2 mpg improvement or so), it would justify the investment. From 46 mpg, my national brand gas toppled the Honda to 41 mpg. I went back to el cheapo and the Honda climbed back to 46 mpg. Conclusions: (1) different gas delivers different fuel economy, so stick to one station while experimenting with other things; (2) expensive gas can work worse than cheap gas; (3) finding the best local gas for economy isn’t likely to be something an article in a national magazine could help with (by now, Fd started contemplating an article).

What could state-of-the-art Kawasakis (or anything else) show me about my Honda? The GPz550 had a six-speed transmission, for one thing, it had a lower first than my Honda (17.91 vs. 15.69), yet sixth was a fraction of a tooth higher than the Honda’s fifth (5.93 vs. 6.00). That’s just an expression; chain doesn’t like fractions of teeth on sprockets. All the same, I started juggling ratios.

Chain drive bikes are messier, noisier, and less reliable than shaft-drive bikes, but gearing changes come cheap and easy. The countershaft (front) sprocket is small; making it bigger means the engine turns fewer times per mile. The sprocket on the rear wheel is large; making it smaller has the same effect. The countershaft sprocket has a couple of other limits to consider though. If it’s too small, the chain has to flex too much going around it and straightening out again; chains and efficiency both suffer. If it’s, too large, the chain starts sawing through nearby parts.

I could install only one tooth larger countershaft sprocket on my Honda—to 18 teeth—before part A (chain) began singing against part B (steel case-saver strap). After fiddling with that for a while, I finally spent $34.82 on a smaller rear sprocket (34 rather than 37 teeth) and shelved my $7.65 countershaft sprocket. Acceleration suffered with the higher gearing and the clutch took more abuse. The engine did smooth out at 60 though. Mileage? Mileage on my Honda didn’t change with the different gearing.

I decided to forget how many times the engine turned each mile—to think of the Honda as a device for converting gasoline into fun efficiently. Certain engine speeds were more efficient perhaps, but perhaps it was time to start making the Honda easier to roll down the highway.

Right in the midst of my ratio-juggling, for instance, I discovered accidentally that the old stock chain was starting to look like a bullsnake with arthritis. I couldn’t find any 530-size chain which claimed any major mileage boosts; most of the fancier chains came only in the larger, superbike sizes. I finally just bought a good quality American chain—about half the cost of a stock Honda chain, but I'd had excellent luck with them for years. Since it was cheaper than stock and replaced a worn-out part, I didn’t add the new chain’s cost to my fuel conservation tab. All the same, that easy rolling new chain boosted the Honda to 47 mpg. A friend of mine had just bought a new 1300cc Harley Sturgis—toothed belt drive instead of chain, 60 mpg! Some Kawasakis used belt drive too (not the GPz550). Food for thought.

continued on page 113

continued from page 109

Mileage gains were coming harder now. I juggled tire pressures, finally settling on 40 psi in each tire as the best compromise between fuel economy, safety, and tire wear—a 1 mpg gain. The Honda wore Japanese Dunlops—4.1 OH 19 front and 4.25/85H18 rear. I wondered about smaller tires—less traction but less drag. I wondered about harder tread compounds—same effect. I wondered about more triangular-section tires like roadracers use—more traction, less drag, but higher wear. I wondered about tread pattern (the GPz550 had a ribbed front tire). Tires cost a lot of money. Figure some special set of $100 tires would save 5 mpg— from 45 to 50 mpg. At $1.25 a gallon, those special tires would pay for themselves in 36,000 miles—longer than the tires would last. I decided to mount somewhat smaller, harder tires when the current ones wore out, but not to rush into anything.

I passed through six stoplights on each leg on my daily journey, and sometimes it seemed as though missing a couple of ex-

tra green lights would make about as much mileage difference as some of the other stuff I was doing now. The crash bars and highway pegs on my bike had provided thrills for a week or so, but the novelty kind of wears off when it’s the seventh or eighth bee flying up your pant leg instead of the first or second. You get jaded. I tried removing the stuff, but I couldn’t see any mileage change so I put it all back on.

Only speed made a consistent difference. Running 60, I still got passed a lot, though I didn’t get sucked into people’s grilles like I did at 55. But if I let my speed creep upward—easy to do when the engine was loafing along with higher gearing—mileage always suffered. So did my paranoia; I didn’t know how far those big 55 signs could be bent. Incidentally, both my speedometer and my odometer were accurate within 5 percent. I rode through one of those 5-mi. speedometer check sections twice every day, and by now I really looked forward to it.

I was checking front wheel balance one evening, but the front disc brake dragged so much I couldn’t even spin the wheel without first prying the brake pucks away from the disc. If 10 psi more air in the tires had gained me 1 mpg, that front wheel traded for one with a drum brake would have gained at least that much more. But the disc did stop the bike much better than a drum would, and besides, that darned GPz550 had not one but three disc brakes on its wheels. Safety won out.

I spent more time looking at magazine pictures of the GPz550 and those other amazing modern misers. Maybe those cafe fairings on so many of them were part of it. The one on the Honda came from the 1952 Seeburg Jukebox school of fairing

design. Big and bulbous, its headlight hid in a short tunnel and the windshield towered so high that I couldn’t see over it. cut a short replacement windshield out of Masonite and screwed it in place on the fairing. Maybe I could make my fairing at least equal no fairing in efficiency.

The first trip with the short windshield, the mileage jumped from 48 to 52 mpg! could feel the wind buffeting my neck— not a deafening blast, but four more inches of shield would help a lot. I wanted the engine to loaf at lower rpm as the bike’s shape got slicker, so I reinstalled the taller, 17/34 gearing.

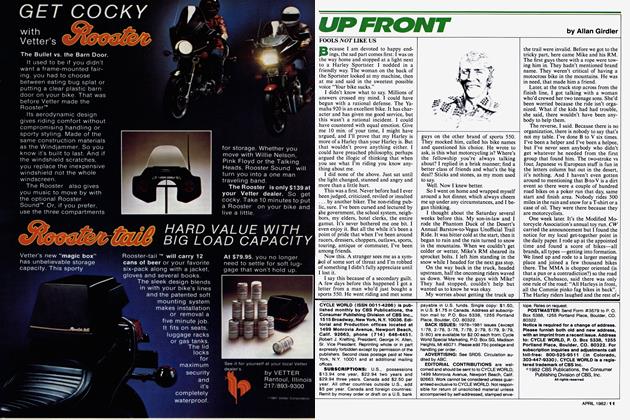

In a move to keep things cheap—especially while experimenting—I went to a nearby lumberyard and bought a thin, transparent cover meant to seal basement window wells. I paid $8.79. Then I studied the results from my extensive gnat tunnel testing conducted over the past few weeks. Gnat’s law goes like this: gnats don’t die on a streamlined surface. Sure enough, the principal insect carnage on the Honda fairing occurred in the little turn signal pockets on either side, in the headlight well, and on the new windshield itself (short, but still too vertical). The Honda’s two big front turn signals and twin mirors also collected their share.

With a grease pencil and heavy scissors,

I made a headlight cover and a bubble windshield out of opposite corners of the window well cover. Proper sheet metal screw mounting would come later; for now, lots of tape and a couple of makeshift brackets held things in place. I masked the turn signal pockets with tape also.

These changes won another 3 mpg for the Honda—up to a nice, round 55.

People who win economy runs cruise smoothly, I’m told, in the highest gear possible, at about 45 mph. My commuting days were almost over now, but I wanted to make one big push for the Honda/me/ project maximum. I started early, planfling to ride 45 mph all the way. After a fairly close call set my Toyotasup

CHECKLIST FOR SAVING MONEY ON GAS

1. Is the bike in good tune—plugs, points, timing?

2. Are the spark plugs burning chocolate-malt-brown or lighter brown?

3. Is the chain in good shape and properly adjusted and lubricated?

4. Are you burning the most economical gasoline you can easily obtain?

5. Do you have a standard, repeatable, fairly long route you can use to check your economy accurately?

6. Is your air cleaner as efficient as possible?

7. Are tire pressures as high as possible without killing tire wear, ride, and handling?

8. Are the tires as small as your riding habits permit?

9. Would higher gearing help?

10. Can you do anything simple and cheap to improve streamlining?

1 1. Are your wheel bearings, brakes, etc. properly adjusted to reduce drag?

12. Does the bike roll and the suspension flex with nothing rubbing, throbbing, or wobbling anywhere?

13. Do the people familiar with your machine type and area have any tips?

14. Are you riding as gently as your Toyotasupposiphobia will allow?

EXPENSIVE STUFF WHICH WOULD PROBABLY SAVE GAS IF YOU NEED AN EXCUSE TO BUY IT

1. Well-streamlined fairing (with or with-

out am/fm/8-track)

2. Exhaust headers (black, chrome, or nickel-plated)

3. Electronic ignition system

4. Belt-drive chain replacement package

5. GPz550 or other new-generation scoot

posiphobia raging, I dialed it up to 55 till I was out among the crop dusters. My 62.5 mile go-to-work trip usually took about an hour and 15 minutes, allowing for speed zones, red stop lights and the like. One hour and 52 minutes after starting on this particular day, I finally dragged into my destination. I'd sung every song I knew, counted the bugs on several folks’ grilles, written most of this article in my head, and promised myself that I was not going to return home at any 45 mph. When I filled my tank at the other end though, it took exactly one gallon—62.5 mpg!

Thus ended the basic experiment. I'd invested $21.35 in an air filter, $34.82 in a smaller rear sprocket, and $8.79 in a plastic window-well cover—$64.96 including tax. This investment had boosted mileage of my 1976 Honda from 34 mpg to 55 mpg under similar conditions—a 62 percent gain. I wasted several bucks on stuff w hich wasn’t on/in the final 55 mpg machine; consider it the price of my education, like tuition. I logged a total of 3 125 monitored miles on the Honda. At 34 mpg, that would equal $ l 14.89 spent on $ l .25-a-gallon gas. At 55 mpg, it would equal $71.02. Just for comparison, a 12 mpg standard Detroit sedan driven those same 3125 miles would have (driven me nuts and) burned $325.52 worth of fuel.

I’ve done several things more since the

commuting ended, though I haven’t forced myself to ride that 125 mi. loop again to test them. For one thing, I remounted the fairing so it looks reasonably aerodynamic (for a 1952 Seeburg jukebox). I made a steel windshield bracket to remount the stock windshield sloped back much more radically on the fairing, removed those fat Honda turn signals from the front, and replaced them with teardrop running lights from a camper supply store (wired parallel with 4 ohm resistors so the flasher will work properly). The teardrop lights cover the fairing’s original turn signal pockets. I also lowered the stock mirrors a little.

I haven’t installed an electronic ignition or good exhaust headers yet, though I may someday. Like supertires, those gadgets might help the GPz550, but they’d never pay for themselves in fuel savings alone for the Honda. Last week though, I was visiting a nearby Yamaha shop. They had this special bargain in obsolete aftermarket rear shocks for the Honda 550 Fours. Where they got ’em, I don’t know; but now I’ve got ’em. Some people would like you to believe that rear shocks won't save two ounces of gasoline in 10,000 miles—and those people are probably right. But less fuel or more fun —any time you make that fuel-to-fun process more efficient, you win. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue