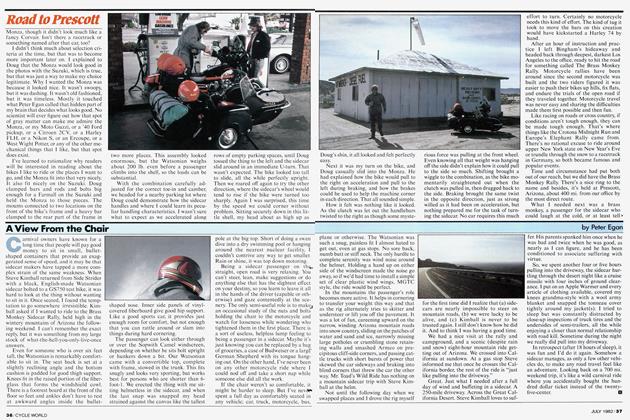

UP FRONT

Allan Girdler

THE SEARCH FOR THE MISSING LINK

When I first sat down to electrically pen these thoughts on paper, the working theme involved failure. I had just got home from failing in a quest.

It’s a quest of long standing. I cannot bear not to know what’s on the other side of the mountain. Any mountain. To see a road or trail is to wonder where it leads. I do this in my neighborhood, on the open road and when the other packees are worrying about whether the pilot feels good or just decked his wife, I am leaning on the window inspecting ribbons of blacktop winding through the trees or noting tracked dirt leading past the ranches into the outback.

In the specific case here, one day I was jamming a multi along the highway next to an old town. A nice old town and, rare in California, a really old town. (It’s the central town in “Ramona” for those who also ►fake research.) My eye caught sight of a trail leading up a canyon parallel to a river. Hm, I mused, the river crosses one of the back roads several miles downstream. The Butterfield Stage used to go from down there to here. Could I ride down that trail from here to there? And if not, where iCtfuld I get from here?

In the course of time we got the latest Honda XL250R—not this month, sorry, all full, watch this space—and when 10 days of rain ended with the first warm and sunny day of spring, I took the Honda and rode off to answer my questions.

Getting through town was easy, finding the bridge over the river in town likewise, & soon I was riding up a rutted old track, and down, and up and down until there was nothing but a few scattered houses at the end of two-rut tracks. This area is less settled and more rural than one expects. It is populated by clannish people, communes who I see mostly at the bluegrass festivals. I suspect they harvest crops not approved by federal authorities. They are friendly when met on the trail but I didn’t figure they’d welcome me in their back yards. Back to town.

Crossing the river on the Interstate I worked my way back towards the canyon on a paved road that became mud and led to a pipeline construction site. I followed the bulldozer spore and came to a stream. It looked possible so I wound on power, closed my eyes, held my breath and plunged across, water up to the bottom of the barrel. Maybe half a mile further along the track led up a slope and across the stream again. The water was half as wide. Well. If the same stream is half as wide, why, then this crossing must be twice as deep. Cross off route no. 2.

I wasn’t working entirely blind, as I had brought along a map of this country. It showed some manner of trail up to a reservoir between my starting point and my hoped-for finish. I found the turn and was churning up through the mud when I saw two horses plodding down through the mud. I switched off and sat back. A dog ambled up and one of the riders, a lady, said the dog didn’t know what a motorcycle is.

A quiet and well-behaved vehicle used only by ladies and gentlemen, I quipped and she laughed. Maybe this one, she said but courtesy had won the day and she said the north route from the top of this trail went to where I’d been, the south route she didn’t know.

From the ridge I could look north and see the crossing I'd forded. I could infer that the trees hid the crossing I’d not risked. I rode south and fetched up on another ridge. I could see the river, where the stage stop used to be and all the way back into the real wilderness, where bears were sighted in living memory. But the trail stopped there. I could see it, but as for riding to it I might as well have been traveling in Columbia.

Back to the highway. The next turnoff took me down to the river, to a valley where the river was wide and the sandy banks were enlivened by gamboling dirt bikes and three-wheelers. Naw, they said, who’d bother us here? They were playing rather than exploring but one man recalled that he’d heard the graded road led, somehow, to the pipeline project. Off I went, lifting the front wheel the way the XLs do in the ads.

The graded road became an ungraded road, a track and then a trail. The streams were tributaries and I splashed through without mishap or apprehension. We wound up the sides of a canyon, heading toward a ridge I reckoned should be on the other side of the valley from the ridge I’d reached earlier.

And maybe it was. But near the top there was a gate across what looked like the main route. The gate was covered with signs proclaiming the violent fate awaiting all who trespassed beyond. There was a path to one side, so I followed that until it came to a hill. A steep hill. I parked back from the edge, walked to the lip and peered over.

I figured I could get down all right, I> mean, you can always get down a hill, it just depends on how high you’re willing to bounce. Back up 1 wasn’t so sure and there was no proof the track went anywhere. Further, there were no tracks on the path* not even any hoofprints. I wondered what our bookkeepers would say if my expense account contained the entry: Helicopter charter, one hour, for retrieving motorcycle from bottomless ravine.

Then I turned around and went back to the pavement for the third and last time at the day.

Due to sagging morale, I went to have lunch at a place I knew Fd enjoy lunch before I ate there. Out on the Interstate there are franchised places that supply mass-produced food for the mass-transit masses. But in the old town there’s a caf&n I’d been there for coffee and noticed the waitresses were eating there.

A statesman once said if you want to respect either sausages or the law, don’t watch either being made. It must follow that if people who watch the food being made eat it, it’s good. And it was. I parke^ up against the hitching post and not even the cowboys minded. (I knew they were real cowboys because they were wearing baseball caps, John Travolta having ruined cowboy gear for the people who need it.)

Back on the highway I was cruising^ noplace when I saw a sign pointing to Rainbow Valley.

The infinite variety of the human race must have produced one person who can resist a place named Rainbow Valley. But I am not that poor benighted realist. I rode past stands of wild lilac, down a country road lined with oak trees in spring green. At the end of the valley I turned left, alona another winding road along another river With 80 mi. on the odometer I remembered I’d forgotten the tank’s capacity. Just as I wondered where I was, another sign said 11 mi. back to the old town, a new and different way and one I didn’t even know existed.

u

So much for failure. True, I didn’t gee where I thought I was going. Instead I went places I’d never been, and found places I didn’t suspect, and now I know where the stagecoach went before the railroad and probably how the Indians got to town before the stagecoach.

Indians? I thought I was talking abofl^ cowboys.

Just past the sign that got me back to civilization with gas to spare, I rode through a reservation. Parked in front of tribal headquarters was a Honda XL250. Like mine.

Yee-Haw, I shouted to myself. I agpr doing like the Romans do, so one of these days I’ll find the road leading to Rome. B8