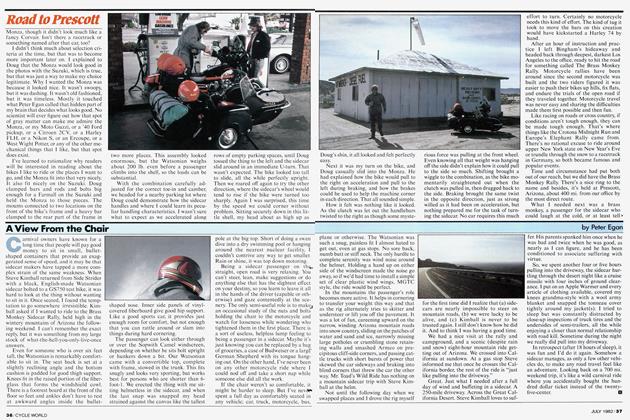

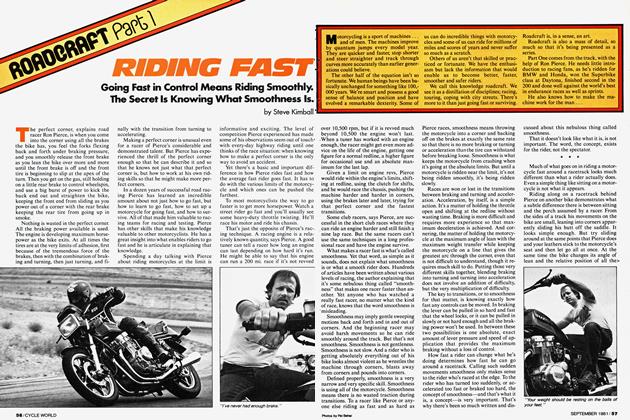

The Road to Prescott

Two Intrepid Motorcyclists Discover The True Meaning of Sidecars (if Not Life) On A Trip To The Brass Monkey Rally

Steve Kimball

Enthusiasts of any product or activity get more fanatical as their numbers get smaller. Motorcyclists are more enthusiastic than car drivers, BMW riders more enthusiastic than Honda riders, Ducati owners more enthusiastic than BMW owners, and on down the list until it comes to sidecarists. Sidecar drivers have a commitment and a fire that ranks right up there with television health nuts. Say something about a sidecar in a magazine and be prepared for an avalanche of mail. Don’t write something about sidecars and you still get a stream of mail from sidecar enthusiasts who want you to write about sidecars.

Assuming a. these people aren’t possessed by the devil, and b. it isn’t contagious, there must be something appealing about sidecars. The only people in motorcycling who have anywhere near as much enthusiasm for their sport as sidecarists are trialers, and now that most of them are wearing helmets, I expect that to decline in the future. But what excuse do sidecar drivers have? They appear to be an otherwise ordinary bunch of motorcyclists. Pants go on one leg at a time, that sort of thing.

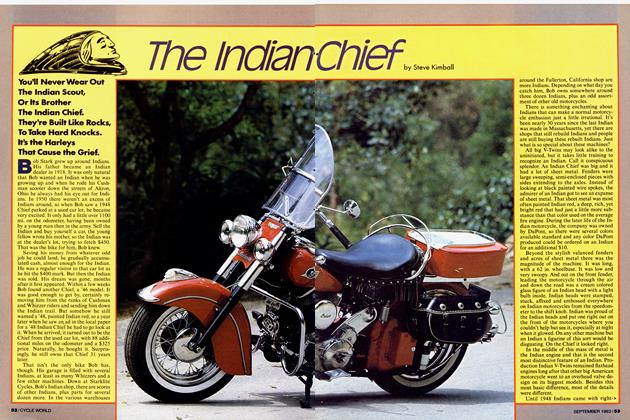

In our never-ending search for truth, justice, et cetera, we were led to Doug Bingham, who haunts a well-known sidecar emporium on the north shores of the Los Angeles area. His business is called Side Strider,( 15838 Arminta St., Unit 25, Van Nuys, Calif. 91406) and he sells a variety of sidecars in all shapes and sizes and colors. Doug has been a fixture in the sidecar scene for many years. He’s raced sidecars in virtually every kind of competition, he’s made sidecars, mounted sidecars and he sells sidecars. He is also an Important Person in the United Sidecar Association, the big national club for sidecar types.

All of this background makes Bingham a good source of information about sidecars. His shop is in one of those low beigecolored industrial complexes filled with little businesses making lefthanded widgets. There is no sign as such, but the shop is continually surrounded by sidecars, as though the Indians were attacking and they were circling the wagons. Like any good bike shop, it was filled by a loyal following, customers who make the shop a home away from home. In this collection, Bingham is the guru of sidecars, but without the affectation of somebody who wants to be a guru.

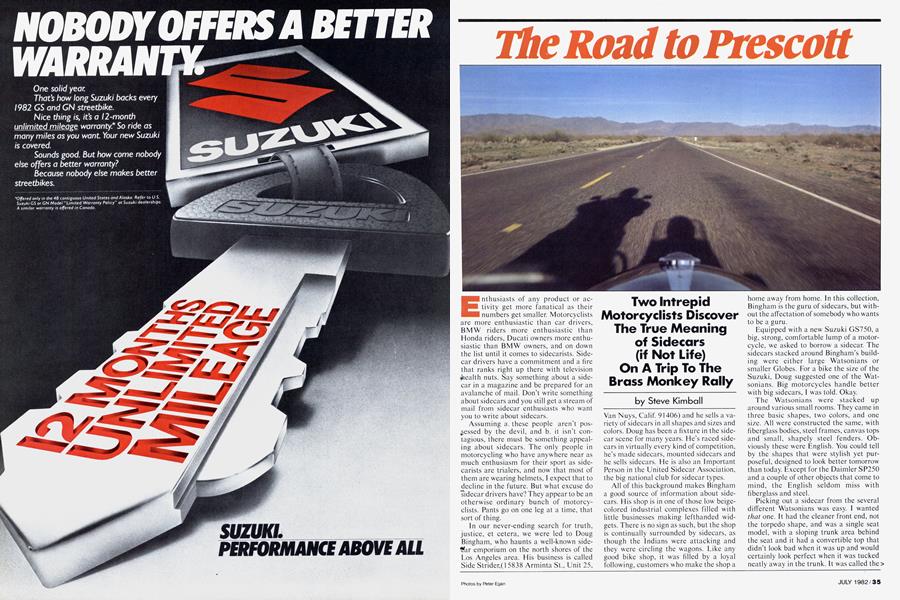

Equipped with a new Suzuki GS750, a big, strong, comfortable lump of a motorcycle, we asked to borrow a sidecar. The sidecars stacked around Bingham’s building were either large Watsonians or smaller Globes. For a bike the size of the Suzuki, Doug suggested one of the Watsonians. Big motorcycles handle better with big sidecars, I was told. Okay.

The Watsonians were stacked up around various small rooms. They came in three basic shapes, two colors, and one size. All were constructed the same, with fiberglass bodies, steel frames, canvas tops and small, shapely steel fenders. Obviously these were English. You could tell by the shapes that were stylish yet purposeful, designed to look better tomorrow than today. Except for the Daimler SP250 and a couple of other objects that come to mind, the English seldom miss with fiberglass and steel.

Picking out a sidecar from the several different Watsonians was easy. I wanted that one. It had the cleaner front end, not the torpedo shape, and was a single seat model, with a sloping trunk area behind the seat and it had a convertible top that didn’t look bad when it was up and would certainly look perfect when it was tucked neatly away in the trunk. It was called the > Monza, though it didn’t look much like a fancy Corvair. Isn’t there a racetrack or something named after that car, too?

1 didn’t think much about selection criteria at the time, but that was to become more important later on. I explained to Doug that the Monza would look good in the photos with the Suzuki, which is true, but that was just a way to make my choice legitimate. Why I wanted the Monza was because it looked nice. It wasn’t swoopy, but it was dashing. It wasn’t old fashioned, but it was timeless. Mostly it touched what Peter Egan called that hidden part of my brain that decides what looks good. No scientist will ever figure out how that spot of gray matter can make me admire the Monza, or my Moto Guzzi, or a ’40 Ford pickup, or a Citroen 2CV, or a Harley FLH, or a Nikon S, or an Ercoupe, or a West Wight Potter, or any of the other mechanical things that I like, but that spot does exist.

I’ve learned to rationalize why readers will be interested in reading about the bikes I like to ride or the places I want to go, and the Monza fit into that very nicely. It also fit nicely on the Suzuki. Doug clamped bars and rods and bolts big enough for a Farmall on the Suzuki and held the Monza to those pieces. The mounts connected to two locations on the front of the bike’s frame and a heavy bar clamped to the rear part of the frame in two more places. This assembly looked enormous, but the Watsonian weighs about 200 lb. even before a passenger climbs into the shell, so the loads can be substantial.

With the combination carefully adjusted for the correct toe-in and camber, we headed for a nearby parking lot where Doug could demonstrate how the sidecar handles and where I could learn its peculiar handling characteristics. I wasn’t sure what to expect as we accelerated along

rows of empty parking spaces, until Doug tossed the thing to the left and the sidecar slid around in an immediate U-turn. That wasn’t expected. The bike looked too tall to slide, all the while perfectly upright. Then we roared off again to try the other direction, where the sidecar’s wheel would tend to rise if the bike were turned too sharply. Again I was surprised, this time by the speed we could corner without problem. Sitting securely down in this little shell, my head about as high up as Doug’s shin, it all looked and felt perfectly easy.

Next it was my turn on the bike, and Doug casually slid into the Monza. He had explained how the bike would pull to the right on acceleration and pull to the left during braking, and how the brakes could be used to help the machine corner in each direction. That all sounded simple.

How it felt was nothing like it looked. As the clutch was let out the handlebars twisted to the right as though some mysterious force was pulling at the front wheel. Even knowing all that weight was hanging off the side didn’t explain how it could pull to the side so much. Shifting brought a wiggle to the combination, as the bike momentarily straightened out when the clutch was pulled in, then dragged back to the side. Braking brought the same twist in the opposite direction, just as strong willed as it had been on acceleration, but nothing prepared me for the task of turning the sidecar. No car requires this much

effort to turn. Certainly no motorcycle needs this kind of effort. The kind of tug it took to move the bars on this creation would have kickstarted a Harley 74 by hand.

After an hour of instruction and practice I left Bingham’s hideaway and headed back through deepest, darkest Los Angeles to the office, ready to hit the road for something called The Brass Monkey Rally. Motorcycle rallies have been around since the second motorcycle was built and the two riders figured it was easier to push their bikes up hills, fix flats, and endure the trials of the open road if they traveled together. Motorcycle travel was never easy and sharing the difficulties made them first possible and then fun.

Like racing on roads or cross country, if conditions aren’t tough enough, they can be made tough enough. That’s where things like the Crotona Midnight Run and Europe’s Elephant Rally came from. There’s no rational excuse to ride around upper New York state on New Year’s Eve or trundle through the snow to a racetrack in Germany, so both became famous and popular events.

Time and circumstance had put both out of our reach, but we did have the Brass Monkey Rally. There’s a nice ring to the name and besides, it’s held at Prescott, Arizona, about 400 mi. from our office by the most direct route.

What I needed next was a brass monkey, a passenger for the sidecar who could laugh at the cold, or at least tell jokes about it. Adventures always work best with pairs. That’s why we had the Lone Ranger and Tonto, Stan and Ollie, Bob and Bing on the Road to Prescott. The only volunteer 1 had was Cycle World’s Poet Laureate, Peter Egan. The only duo we would resemble would be Mr. Hand and Mr. Bill, but in this case 1 got to be Mr. Hand, so that was okay.

Prescott is about 6000 ft. above sea level, an elevation that assured some kind of cold w'eather and probably snow. We packed every piece of rain gear and warm clothing we owned. In addition to the Belstaff jackets and pants we had electric clothes, wool sweaters and army blankets. For colder weather we were ready to put on long johns, sweaters, jackets and overpants and outer jackets, giving us each the physique of the Hindenburg, but not its ability to get warm in a hurry.

Being good company men we decided to get an early start and have breakfast on the road because we could pay for our food with a company credit card if we were on a trip, and we were on some trip. That gave us a good opportunity to check our temperatures and comfort after an hour of riding, and we were both a little surprised how well things were going.

Peter was more placid in the sidecar than in any other vehicle I’ve seen him in. Sitting down there in the hack he would stay silent for minutes at a time, a talent his second grade teacher would appreciate knowing he has mastered. Of course communication between rider and passenger is far more difficult with a sidecar than if two people are riding the same bike. Our full coverage helmets, worn in the interests of keeping frostbite off the chin, didn’t help.

Life on the Suzuki was pleasant enough. The Pacifico Aero-foil fairing provided as still a block of air as I’ve ever felt behind a fairing. Unless there was a sidewind things were peaceful and comfortable. The Suzuki was running like a champ, actually it was running better than any Studebaker I ever drove, but what better way is there of saying it was doing nothing wrong? Cruising across the desert w'e settled in at about 65 mph. Oil temperature would climb to around 300° if we cruised much over 70, so the slightly lower pace kept the stock temperature gauge of the 750 happy without getting us run over by diesel cars.

Nearing Palm Springs the traffic changed. So did the air. The sickening stench of diesel-polluted air was once again noticeable. Towns like Palm Springs and Newport Beach are more afflicted with this problem, the rich having found the diesel Mercedes fits both their social conscience and their desire for conspicuous consumption.

Life got better the other side of Palm Springs as a tailwind found us and catapulted our speed up to 70 with the oil temperature gauge still holding under 300°. Desert scenery has always appealed to me, as much for its scale as anything. Thinking of people venturing across hundreds of miles of the Mojave without freeways, motorcycles, or company credit cards stretches the imagination. Even with these conveniences it’s a full day’s ride to cross the desert, especially when the range of the motorcycle is reduced to about 120 mi. between fillups because of the lower mileage of the sidecar rig. With our tail wind mileage was running about 37 mpg, and without the tailwind it would drop more.

February is a good time to cross the middle of the desert, being a little warmer than the middle of winter, but well out of the poached-rider temperature range that begins a couple of months later. Winds haven’t picked up too much, and there is little rain. Even if there had been rain we probably wouldn't have put up the quaint little top of the Monza. It fit well enough, and appeared to be as waterproof as a rock, but it wasn’t designed for an economy-size passenger, and when we tried fitting it around Peter the top had to stretch and he had to fold to get all the snaps done. Peering out through the side window in the top he looked like someone in a television set, only a lot less happy. That’s what rain gear is for, so the top stayed in the trunk of the sidecar, along with most of the other cold weather gear and anything else that would fit.

Riding along Interstate 10 is seldom much fun because all you do is hang onto the handlebars struggling against the wind and try not to think about the suffocating heat. This was different. The wind was behind us, the temperature was in the low 70s and the quiet colors of the desert were visible after the winter rains. There is a long grade in the middle of the California part of the highway, for 20 mi. it steadily climbs from the desert floor while signs along the highway warn motorists to shut off their air conditioners to keep from overheating. Not having any air conditioning that we could shut off if we had wanted to, we slowed down a bit, dropping down a gear on the steepest sections while watching the scenery and the overheated cars along the road.

At the summit of this grade is the sort of automotive oasis that springs up wherever things with engines overheat. Beside the newer gas station was the old building, with signs on it advertising “air wrench.” A junk yard extended out behind the station as far as a person could drag old used parts. Preserved by the dry desert air were rows of slightly rusting old hulks, all built before signs warned them to turn off air conditioners to avoid overheating. It didn’t help. Long, hot, straight climbs were too hard on Essexes, and LaSalles and Hupmobiles. Motorcyclists climbed those same grades on Hendersons and Indians and Harleys, only the junk yard hadn’t claimed their bodies. Motorcyclists must be more civilized, 1 expect, and always retrieve their bodies from the battlefield. Either that or motorcyclists had the mechanical ability to fix their bikes and go on.

Suzuki’s GS750 is a big, fast bike, the kind of motorcycling equivalent to something Gatsby would have driven. Hooked up with the Watsonian it was smooth, powerful and quiet, and it had a soft, big seat that made sitting a lot more fun than walking or running or any of those other ways of crossing the desert. There are machines that make just cruising a pleasant task. Harley-Davidson makes several of them, Moto Guzzi and BMW make bikes that are happy just going down the road, and with the Monza beside the Suzuki, it became more of that kind of machine. Following the advice of Doug Bingham, I hooked a bungee cord from the left side of the handlebar to the frame, the bungee counteracting the rig’s tendency to pull to the right when cruising at about 65 mph.

How a sidecar is mounted to the bike determines if the rig will pull to the left or right or go straight at a particular load. It’s not controlled by toe-in of the sidecar’s wheel, but by the camber of the motorcycle. The sidecar may look level when it’s unloaded, but with a rider on the motorcycle the rig leans to the left. This creates a little left caster to the bike, so that the bike wants to steer left, counterbalancing the sidecar’s pull on the bike to the right. Of course this changes with roads and loads and even the speed, so a little steering assist like the bungee helps out on long trips.

With the bungee wrapped once around the handlebar, the Suzuki was comfortable at normal highway speeds without any noticeable pull to one side or the other. Up hills and into headwinds there was more pull to the right, but slowing down it went to the left, all easily correctable. All these actions and counteractions added inertia to the steering, so the bike was happiest on the Interstate, where it would occasionally bounce one way or the other, but went mostly straight ahead.

As long as the weather is nice and the scenery around the freeway interesting, this doesn’t make for a bad way to travel. Added to the scenery beside the road, there is scenery on the road, and the sidecar accentuates this. Everybody loves the sidecar. Old ladies in big cars smile and wave. Young girls want rides. Highway patrolmen are more amused than challenged. It’s hard to imagine anyone ever saying, But I didn’t see him Officer, about a sidecar. Blessed with a 100 mi. range between fillups, we did a lot of stopping and always gathered a comment or two and a small crowd. Usually the talk was predicable, “Ya shore don’t see many of them things.’’ “I bet that thing’s fun to ride in.’’ The comments always ran toward enthusiasm and wonderment, no matter how simple the words.

On the road to Wickenburg, veering off the Interstate, the combination was as pleasant as it was on the four lane. These were two-lane roads, straight and a little rougher. Increased camber on the road made the sidecar pull a little more to the right.

Things became more interesting heading up the winding mountain road up to Prescott. It is the classic up-the-side-of-amountain road, with lots of switchbacks and tight corners. Here the combination was decidedly different from a solo motorcycle. It required lots of muscle to steer the rig through the corners. If the bungee cord helped turning to the left, it added to the effort turning to the right.

Just climbing required more power, and more power from the bike meant the sidecar wanted to pull more to the right. After a while I began trying to take advantage of the engine and brakes to turn the combination, accelerating harder for righthanders so the bike would pull itself around the sidecar, and slowing on lefthanders so the sidecar would pull itself around the bike. Occasionally a particularly tight corner would come up and I’d try to slide the chair in a lefthander, or maybe lift the rig into the air on the righthander, though the considerable load in the hack made that difficult on even the tightest corners.

Part way up the mountain 1 pulled over and plugged in the electric suit. It was getting chilly as we climbed up around 6000 ft. and the sun was going down. We started seeing patches of snow on the ground in the shade of mountains or trees. Pine trees were appearing, more and more of them. Passing cars and campers was hard with the sidecar. You couldn’t just dart around them, power being scarce with our combined 1200 lb. and the thin air. Also, the combination was wider than a bike, so we couldn’t just slip between campers and other traffic. It was more like driving a truck than riding a motorcycle, though not very truck-like, either.

By the time we topped the ridge, my shoulders ached. Steering a sidecar rig is a lot of work on mountain roads. According to Bingham, this combination steered well and didn’t take too much effort, yet here I was running out of power for steering and having to slow down more for corners than we could have gone.

According to the engineers, sidecar rigs have the same vehicle dynamics as cars, not motorcycles. A motorcycle doesn't have any roll stiffness, and the sidecar certainly does. At least up to a point it does. And it depends on which direction it’s turned. Twist the thing into a lefthander and it will ultimately slide, all quite controllably. With enough power on the front tire of the bike can be made to push, even cranked over full to the left, while the front wheel skates along the pavement, going straight ahead while jumping up and down. Righthanders are the fun part of sidecars once a rider gets some experience. Go too fast around a righthand turn and the sidecar will pick its wheel off the ground like a dog lifting its hind leg. Empty it didn’t take much provocation to raise the sidecar’s wheel.

With 200 lb. of sidecar fodder jammed within its fiberglass form it didn’t fly into the air as easily. There must be something to this notion of road-hugging weight, I thought, wrestling the rig around a righthand corner, all three wheels planted firmly on the road.

By the time we were at the edge of Prescott, the sun was down as was the temperature. Finding a sidecar rally in Prescott, Arizona was more difficult than I imagined. It’s not the same as finding motorcycles in Daytona during Speed Week, or the annual Gold Wing Road Riders Association gathering in Arizona. This wasn't that kind of gathering. There aren’t as many sidecars as there are Gold Wings or motorcycles. Even in a smallish town like Prescott they can hide very well. A little searching around the edges of town, where most of the campgrounds are, turned up a hearty band of three wheelers. Most of the group was in town having dinner and as soon as our tent was pitched by the light of our headlight, we followed the distant sounds of grumbling stomachs back into town where we found a row of sidecars in front of a restaurant.

Joining other sidecarists is sort of like discovering your long-lost family, the ones you were taken from by the wolves. They are happy to see you and friendly and in very little time you are a part of everything.

That brings up the matter of clubs. The point of a club is to keep people out, because otherwise it wouldn't be a club. That’s where rules and bylaws come in, being the methods used to exclude people not like us. Sometimes clubs get carried away in the efforts to keep people out because so many people want to join. In these cases the rules get tighter and the entrance becomes more difficult and the club is exclusive because the club members want it that way. Sidecarists aren’t like that. The club is small not because it tries to keep people out, but because so few people want in.

Greetings at a sidecar gathering go, Hi, Where you from? and What did you ride? Only the answers to the last question are more difficult than usual, because of things like our Suzuki and Watsonian. Another common answer is “An R90S conversion in a slash-two frame with a Steib chair.”

When everyone returned to the campsite the range of machines becomes more obvious. Not only can the bikes vary as much as any gathering of motorcyclists, but the sidecars add to the combinations, making two rigs of the same motorcycle and sidecar highly unusual.

The difference in machines makes it easier for all these people to come together. If we had all arrived with the same combination of bike and hack there would have been much less to talk about, and it would be harder to argue the merits of the various combinations because we would have all had the same experience. Either we would have all said the same thing, making for a dull conversation, or we would have all disagreed about the same machine, making for unending arguments. Instead, the variety of machines allowed us all to inform each other, and to receive other comments from people with experience unlike our own. A happy state of affairs.

Here we were, bundled up like so many contestants in the Michelin Man lookalike contest, huddled around a fire. There were no contests pitting one rider against another rider. Instead, we were all competing against the elements, feeling like heroes in a Jack London novel.

Despite predictions of 20° weather at night, it didn’t get noticeably cold, probably not much below 40. No one said anything, but we felt somehow cheated at not having to suffer in freezing cold. There was no more snow on the ground, no wind and no rain. We folded up the tent the next morning and headed up the road to Jerome for breakfast, no ceremonies or speeches ending the gathering, just a bunch of people going their own way as suddenly as they came together.

Between Prescott and Jerome there’s a high mountain pass, snow several feet deep on both sides of the road. It was cold, cold enough that a snowman beside the road still stood, no hint of his age. “Not a bad snowman,” I yelled to Peter, pointing off the road. “There are no bad snowmen,” he yelled back, “only bad children.” Just for that I hit the next righthander faster than usual to elevate, if not the humor, then the comedian.

Another half an hour of swaying back and forth around mountain hairpin turns and we descended into Jerome. A hundred years ago this was a booming mining town. Stone buildings were stacked on the hillside from which the ore and the stones for the buildings came. The only flat part of Jerome has been graded from the hills. There is a narrow street that switches back and forth, creating two rows of buildings, one above the other. Most of the great, crumbling stone buildings are empty now. There’s a mining museum on a nearby hillside, and tourist shops and artists’ abodes fill the buildings that aren’t crumbling or falling down. The first restaurant we found open looked perfect. Wooden screen doors were held closed with long, rusty springs, just like the kind back on the farm. Inside were old wooden booths and a rustic charm left over from a time when sidecars weren’t so odd.

We ordered breakfast and were surprised when the coffee arrived in styrofoam cups. At a picnic plastic cups are bad enough, but sitting here in what looked like grandma’s kitchen, in the middle of this town built of rocks, these cups were as out of place as highway pegs on a 900SS Ducati. Still grumbling over the plastic cups filled with not-very-fresh coffee, our breakfast arrived, on paper plates, accompanied by the kind of plastic forks that break off in potato salad and poke holes in your mouth when you accidenJ tally discover the broken part. About this time other members of the sidecar gathering poked their heads into the cate and said they were going to the restauant around the corner that comes so highly recommended.

Before leaving grandma’s kitchen we chided the waitress over the lack of a dishwasher. The problem, she informed us, is that the county health department requires a restaurant to have three separate sinks for washing dishes. This restaurant having been built before there were health departments, there was no room for the extra sinks, so they were stuck using paper plates and plastic cups and forks and spoons. Like the 55 mph speed limit and helmet laws, here was another example of laws written to eliminate some theoretical danger, the only result being a lesser quality of life.

From Jerome we searched for a tiny road promised to us by an old map. It would have cut through low elevations in the Prescott National Forest to the northern highway at Williams, making for a nice loop back to Newport Beach. This didn’t happen. The secret road is still a secret. Somewhere on the edge of Clarkdale at the bottom of the mountain there may be this road. It’s probably dirt or gravel, and it’s not very direct, but it was the road we wanted.

Headed north and without our shortcut, we kept going, through the scenic Oak Creek Canyon up to Flagstaff. The distance is short, but the elevation is high, and the temperature was low.

On the wet, muddy and sometimes slushy highway the sidecar was confidence inspiring. There was no question it wouldn’t fall over, and the single drive wheel had no trouble finding traction on the worst of surfaces. It was easy to imagine sidecars being used in enduros or motocross, the rider and passenger working weight around to keep the machine controllable. That kind of nonsense would be fun on three wheels. But here and now switching the electric suit on and off was as challenging a task as I needed.

Whatever was falling out of the sky was melting when it hit the road, making the trip uneventful, if cold. When we crossed the main highway, what used to be Route 66, we headed west, down the mountains to warmth and straight roads.

Heading back across the desert, piling on hundreds of miles through no more effort than sitting on the bike and holding the throttle open, I thought about that a lot. There is an endless search for The Easy Way, whether it’s the easy way to travel or the easy way to entertain ourselves. We now have easy ways to make coffee, remote controls for television sets, Interstate highways to travel on; we have easy chairs, easy over, easy does it, easy riders, and easy lovers. Easy living may seem like a good idea when a person is working hard, just like the Interstate is a great idea after you’ve wrestled a sidecar through a winding mountain road, but it isn’t of itself satisfying.

Motorcycles and sidecars fit into this thinking nicely. A motorcycle isn’t the easiest way to travel, nor should it be, though there are countless thousands who work very hard trying to make it easier.

A motorcycle is a sensuous device. It treats our ears to pleasant sounds, pulls on our muscles as it accelerates or brakes, spins our sense of balance on curves, brings us to feel and smell the air, and all the while it pleases our eyes when we look at it. It is not rational as a transportation device, what with diesel econo-boxes providing 50 mpg and more utility, but it is highly rational as a sensation-provoking machine, for nothing can so exercise the senses as a motorcycle.

I was comfortable with the sidecar by this time. It still took physical effort to turn, but it wasn’t awkward. It went where I wanted it to go and I didn’t have to think about controlling it. All that was practiced and normal now, just as riding a solo bike had been before.

Some bikes are immediately pleasant and lose their appeal the more I’ve ridden them, and some grow on me the more I ride them. The sidecar is one of the latter. It takes time and miles to get comfortable with the handling and the performance of the sidecar, but time takes care of that.

Back at the office the sidecar was still fun. It was convenient for hauling things around that don’t fit on normal bikes, and of course it always gathered a line of guests for lunch rides. Even when I had nothing to carry and other bikes around, I found myself using the sidecar for normal transportation just because I had adapted to it.

All the reasons given for sidecars were still just reasons. A sidecar isn’t the ideal transportation device. It isn’t as easy to ride as a solo bike, it isn’t as fast, and it isn’t warm and dry and comfy like a car, even a car that uses no more gas than a sidecar. No one will convince the true believer of this, of course, but sidecars aren’t going to put General Motors and Toyota out of business.

None of this means sidecars aren’t worthwhile. Put in the larger scheme of things, every worthwhile endeavor is in some way impractical. Ask your mother. All the fun things you ever wanted to do as a kid were not good for you. You weren’t supposed to play in mud puddles, you weren’t supposed to be eating candy before meals, you were supposed to be in before midnight, you weren’t supposed to ride motorcycles, you weren’t supposed to drive fast and you shouldn’t smoke. There were a lot of reasons why Ben Franklin shouldn’t have been out in a storm flying a kite, why Soichiro Honda couldn’t build a motorcycle, and why Joe Parkhurst couldn’t start a motorcycle magazine. All the reasons against doing something are valid and there are no good answers to them, as any teenager knows.

What can’t be explained is fun. Riding a sidecar is somehow fun. There manages to be a satisfaction in conquering this strange device, and once you’ve mastered it, it’s fun to ride. Si