DEALING with DEALERS

David Mallet

The situations are endlessly familiar: You saved for months and finally purchased a beautifully-chromed 4-into-l exhaust system for your beloved Yamaguchi 50 (never minding that it has only one cylinder). A week later, your neighbor’s pet beagle, Amos, decides to stake it out as his territory. You walk into your garage that evening and discover that the $200 pipe on your precious Japanese antique has rusted so badly it looks like a shredded Brillo pad that lay overnight in a rain puddle.

The dealer says: “Take it up with the distributor.”

The distributor says: “Take it up with the manufacturer.”

The manufacturer says: “Read our limited warranty. It doesn’t cover abuse by beagles.” Or, “Send it in a wooden crate 2500 mi. to Ogallala, Mississippi, via Pony Express insured, and for a $50 service charge, we might get to it in a month.” Later that week, while riding around on your Honda 750F and still seething over the expensive pipe that turned into 10 cents worth of ferrous oxide, you detect that the turbine-like engine of the Honda has begun to sound more like a Mack truck laboriously climbing Mount Everest. Upon careful examination, you learn that the pimply-faced mechanic who performed routine servicing on the Honda last month didn’t know an inner tube from a brake shoe and adjusted all 16 valves “nice and tight.” The valves and valve seats now resemble the surface of an overcooked marshmallow.

The mechanic says: “(Nothing, because he quit last week after finally saving enough money to take a correspondence course in motorcycle mechanics).”

The service manager says: “(Shrug).” The dealer says: “Where’s your proof that my guy did the damage?”

In both instances, you know you’ve been sent to the end of the line. None of those parties responsible are willing to voluntarily ’fess up and compensate you, the innocent motorcycling consumer, for your out-of-pocket losses.

In almost all instances, apart from those involving personal injuries or economic losses over an approximate amount of $2000, you can effectively forget about having a lawyer represent your interests. The reason is simple enough: it costs too much. Since the $200 claim is often as complex as the $100,000 suit with respect to facts and issues of law, by the time your private attorney has merely analyzed your claim, you’ve spent more than you had lost in the first place.

This lack of access to qualified legal representation in small matters leaves you in the unenviable position of having to solve the wrongs by yourself.

In general, the motorcyclist who has established an ongoing commercial relationship with an established dealer will achieve better satisfaction once something goes wrong than will the one who buys bikes, parts or services from Discount Dan down the street. In the latter situation, it can almost be expected as a matter of practicalities that Dan does not provide good after-purchase service or a wellstocked parts shelf. Shopping around for price is one thing, and, as a matter of stimulating competitive free enterprise, should be encouraged. However, be careful that the $100 you saved on the sticker price doesn’t end up costing several times as much in the long run.

The steady customer who is known at the counters undoubtedly receives better after-sale service. Goodwill is an essential part of any business, particularly in motorcycling, where accessories, parts and service costs are substantial. The reputable dealer recognizes this element of goodwill and will strive to keep the customer satisfied—to a point.

You, the consumer, must bear part of the burden of establishing that goodwill relationship. Continually spending money at the dealership is a guaranteed way to make any dealer think that Christmas rolls around every time you walk through the door with a bulging wallet. Unfortunately, this weekly tithe towards accessories and new machines is highly impractical for most of us regular, two-wheel loving folk. But, regular purchases, even if on a small scale, engender familiarity. You’ve ingrained on the dealer’s mind, that if things continue to your satisfaction, you will continue to spend money and may one day purchase that six-cylinder, highpriced baby you drool over every time you enter the shop to purchase another oil filter.

The dealer knows something we almost hate to admit: most of us are hooked on the technological version of the horse and will continue to spend money on newer, more expensive (and faster and bigger) motorcycles until we at last reach that decrepit age when we trade the two wheels of a motorcycle for a wheelchair in the old persons’ home. A smart dealer knows he may have us for 40 years, spending more as we get older. Our goodwill is his retirement.

Your part is knowing where the end line of that good will is. If you spend too much time complaining about the 59 cent toggle switch that didn’t toggle or the gasket that didn’t gasket, the dealer will quickly realize that you’d be an even bigger headache once you purchased the $4000 machine that, for him, spells a weekend vacation in Hawaii.

Dealing by mail can be a greater pain in the posterior than the worst motorcycle seat ever made. Because you don’t have an opportunity to show the manufacturer or long-distance retailer your enthusiastic face, there is an important personal element missing in the transaction. Apart from carefully selecting the mail order product, your only method of relying on goodwill is to let the dealer know that you are a serious consumer who spends 50 percent of his (or her) weekly take-home orr after-market parts such as his.

Prior to becoming involved in difficulty, you should take the first steps toward selfpreservation:

1. Check with friends, read test evaluations and obtain any information you can about the dealer and the product.

2. If possible, inspect the product carefully and make your own visual comparisons with similar products offered by competitors. Most of us love to make spot purchases: we’ll walk into the local dealership for that simple, cheap oil filter and walk out with a heavy chromed luggage rack and light wallet. Take the time to compare.

3. Before purchasing, read any warran-^ ties that come with the product. Forges any sales pitches you hear about how goocT? the product is. While the salesperson can. provide knowledge about the product, you are the one paying for it and who has to use it.

4. In the case of services, attempt to obtain some type of written guarantee. Always request that a written estimate be given and that you will be notified of any problem. Many states have enacted laws which provide that services rendered in excess of the estimate, without written authorization to proceed, cannot be collected by the dealer.

How To Get What You Pay For

5. As the most general rule, if you have any doubts about the quality of the product or service, walk away and do not buy the product or services until you are absolutely certain of your continued satisfaction.

6. In dealing by mail, attempt to obtain as much information about the product, particularly about warranties and authoHzed repairs. The warranty may be generous, but if it entails a “service / charge” of a sum greater than the l product originally cost, the warranty . is worthless.

In short, by checking out duct and dealing with selk have an established track reo both providing a Quality pro

duct and backing up its reputation, you can minimize the > trouble and maximize your riding pleasure.

If you have purchased a lemon—be it a motorcycle, parts or poor service—your sole objective is to be “made whole again.” Unfortunately, the laws in this area are either (a) confusing, (b) overlapping or (c) nonexistent. But, since your primary goal is to get your current three-speed transmission back to working as the six-speed ÿou originally thought you had bought, the precise legal theories must give way to the practicalities.

Disregard verbal warranties, whether made before or after the sale. If you believe something the seller promises apart from the written statement of warranties: caveat emptor. Later, the seller won’t remember what he said and will point to the written warranty. Not only that, but this type of “But you said. . . .” conflict is what bitter disputes are made of. If you and the seller become embroiled in the fertile area of conflicting verbal promises, compromise becomes nearly impossible.

In essence, warranties are nothing more than promises about the nature of a product. The fancy, usually incomprehensible, document that falls out of the packing box is an express warranty. Advertising in magazines or other media, including the seller’s own brochure, may contain express statements that can be construed as warranties. If the seller claims that his product is better than the competitor’s, the statement is probably not a warranty. However, if he claims, for example, that his new helium-alloy shift lever will make your Kawasaki KZ1300 several hundred pounds lighter and, thereby, suitable for flat-tracking, you bet you have an express warranty.

In addition to the express, written warranties, the law also provides what are known as implied warranties. In these days of enlightened consumer protection, you may rely on the fact that a seller is obligated to provide you with a product that is of average quality according to prevailing industry standards. As well, if the manufacturer states that the product is suitable for a specific purpose (e.g., a racing megaphone), you may be able to recover for breach of warranty even though the pipe turns out to suitable for street use, but not for the track.

The limited warranty you always throw away with the packing box varies considerably from manufacturer-to-manufacturer. It is the seller’s attempt to limit his liability, if only with respect to the length of time of coverage. However, if the defect occurred prior to the expiration of the warranty, it generally doesn’t matter that you didn’t discover the defect until after expiration. The seller will possibly claim that the defect resulted from ordinary-wearand-tear, particularly if there has been a substantial time lapse between purchase and claim. However, many states do not allow the seller to limit the time under which a claim may be brought for an unmerchantable product—one which was designed or manufactured below the average quality of prevailing industry standards. In such cases, the warranty is endless. And, since your claim will generally be that the product was not merchantable, the limited warranty isn’t quite as limiting as you thought.

As an example, a major Japanese manufacturer produced a middleweight motorcycle 6 or 7 years ago that was notorious for leaking head gaskets—$5 for the part, $150 for labor to remove the engine from the frame and disassemble a complex upper end unit. In many instances, owners of those oil-spitting machines didn’t discover the defect until long after the express warranty had run out. But, since the defect was a general one that applied to the whole production run of that particular machine, the time limit of the warranty did not apply.

In sum, if the product broke only because the state-of-the-art wasn’t what you thought it should be, forget about the complaint. On the other hand, if the particular product you bought turned out to be less than what the competition offers as average quality, pursue the claim until you receive results.

Faulty servicing by those few inept dealers often causes more headaches than defective products. A know-nothing mechanic can virtually ruin a $3500 machine in 10 minutes of knuckle-busting frenzy. Your protection as a consumer for faulty services does not, technically speaking, come under quite the same laws as do products or goods. However, all states provide varying degrees of protection. In general, you will take an identical approach: a dealer who undertakes services impliedly warrants that all services will be of average quality according to prevailing industry standards.

Once you have had the unfortunate experience of receiving a defective product or slipshod services, you have several choices:

1. You may forget about the matter, which, in this day of the enlightened consumer, is unforgiveable.

2. You may write the editor of your favorite motorcycle magazine. But, while the editor undoubtedly sympathizes with many complaints, neither he nor the magazine has the time or financial resources to provide the forum.

3. You may attempt to resolve the matter in an unfriendly manner with the seller. Although personally approaching the dealer himself with your 360-lb., karate black belt friend, Elmer, may occasionally be an effective form of self-help, it is a tacky, short-lived approach.

4. You may attempt to resolve the matter in a friendly fashion with the seller. > In the long run, the latter approach is the only workable one. If you approach the dealer on a personal level, you may find either that he has a quick, inexpensive solution that makes everyone happy, or you may discover that you were wrong about the defect. But, give the dealer a chance.

If the dealer refuses to negotiate, send him a polite demand letter. This letter should be typewritten, cordial and profes~ sional. Include the following essentials:

I. Photocopied proof of purchase.

2. A detailed statement of the nature of the defect.

3. Date of discovery of the defect.

4. A statement that the defect was of design or manufacture and that the prot~ uct was below the average quality of pre vailing industry standards.

5. A statement that you used the prod uct in the normal fashion contemplated by the manufacturer.

6. A statement of your exact damages.

7. A request for relief.

Send the demand letter via certified mail, return receipt requested, and retain a photocopy for your own file.

When the seller responds, do not turn down a reasonable offer merely because you feel you should stand your ground on principle. It is better to compromise with the seller over a few dollars than it is to risk losing it all and having the mattcj drag on for weeks or months, to everyone's increasing irritation.

In many instances, you will be dealing with more than one seller. For instance, if the Electro-Vibrator Super Cruiser Ra coon Custom seat on your Honda XL 185 catches fire and incinerates, you may wis~ to include as parties liable the manufac turers of the racoon fur cover, the electri cal components, and others, if different from the assembling manufacturer or seller who sold you the goods.

If you have written the demand letter and have received either no response or a negative one, you should elect to contaci your state's consumer protection agency Most of these fuzzy-headed bureaucrats are knowledgeable, diligent and con cerned. By nature of the system, though, the process of relief is more tedious and less effective than private suit. However. by using the CPA, you will (1) learn some thing about the protection afforded you under local law, and (2) show the seller that you mean business.

Normally, the CPA will send you a stan dard printed form that requests most of the same basic information contained in your demand letter to the seller. When yoi~ return the filled-out form to the CPA, in clude a copy of your demand letter and theselier'sresponse.

After the agency receive~s your com plaint, it will review the facts for merit. If a bona fide problem exists, the seller will then be contacted for a response. It may be months before the CPA takes any affirmative action, particularly where a small amount of money is involved. In the meantime, pester the agency for as much information as possible, and write anything important down. Think of it as a quickie legal education paid for by your own tax dollars.

If you have wrung the CPA for all it is worth and the results are still unsatisfactory, you are then faced with a decision of Tvhether or not to sue. This decision should not be undertaken lightly. What may be an aggravating pain in the posterior to the owner of the charred racoon seat nonetheless could be a non-meritorious claim. Remember. where there are personal injuries, even a singed fanny hair, consult an »attorney.

In general, beware of frivolous claims. Costs of suits borne by the retailer and other sellers are always passed along to the consumer. This means that your motorcycling buddies may ultimately support a claim that should never have gone to court.

If you decide to sue for monetary loss your forum will be small claims court, in which you’ll act as your own attorney. The rules vary from state to state, so it will be necessary for you to understand the basic details of how to proceed. Most courthouse clerks will provide you with pamphlets (tax dollars, again), and, although clerks are prohibited from practicing law, they are generally more knowledgeable about small claims procedures than many lawyers. Since you pay the clerks’ salaries, call them and visit them and call and ask them and ask 'em again when you don’t fully understand something. Play dumb and polite for the clerks—and intelligent and extra-polite for the judge. If nothing else, the clerks will point you in the direction of the courthouse steps and show you how to fill out the forms.

Over the past few years, the motorcycling industry has burst from Soichiro Honda’s small garage to a vast series of plants that manufacture technological marvels. Compared to the auto industry, motorcycles have progressed tenfold. Many of the growing pains experienced through the 60’s and early 70's have abated. Fly-by-night dealers and manufacturers of silly racoon custom seats have become fewer in number. For the most part, dealers and manufacturers are willing to stand by their products. For your part, be ethical about complaints. Chronic complaints slow the progress of our industry and make everything more expensive for your buddies. Justifiable complaints, though, contribute toward improving the breed. Your role as a consumer is to verbalize complaints when they exist, and to ride along the highways and trails when they don't. S3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontInnocence Vanquished, Fatherhood Victorious

June 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1981 -

Department

DepartmentRoundup

June 1981 -

Competition

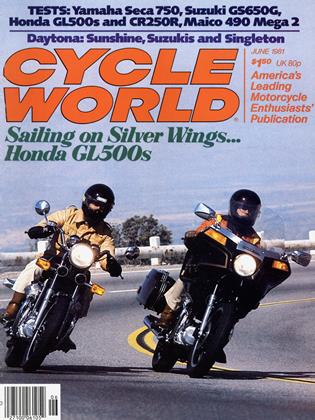

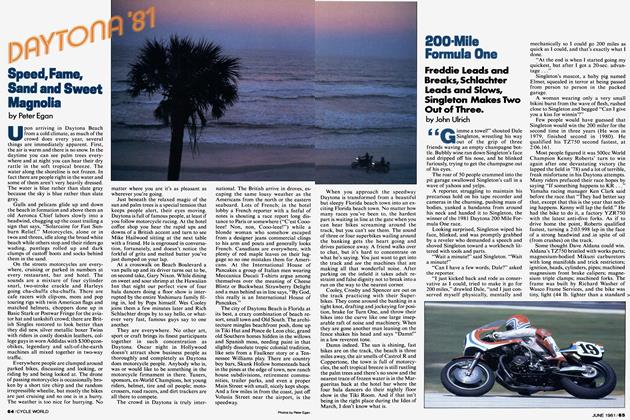

CompetitionDaytona'81 Speed, Fame, Sand And Sweet Magnolia

June 1981 By Peter Egan -

Competition

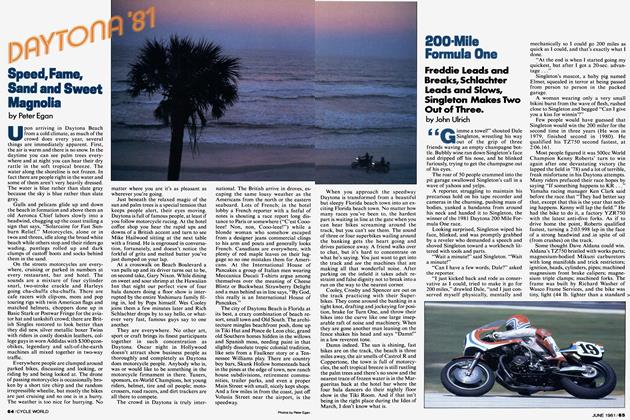

Competition200-Mile Formula One

June 1981 By John Ulrich -

Daytona'81

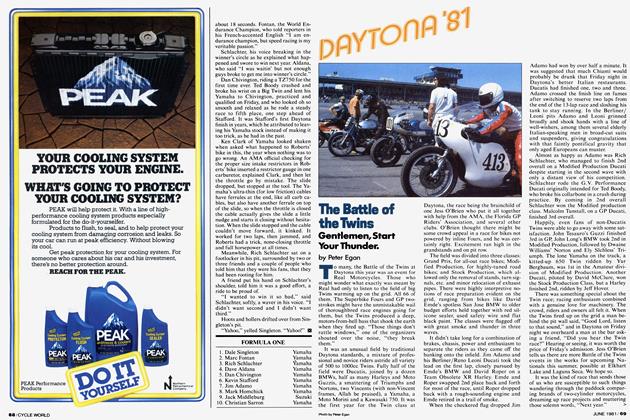

Daytona'81The Battle of the Twins

June 1981 By Peter Egan