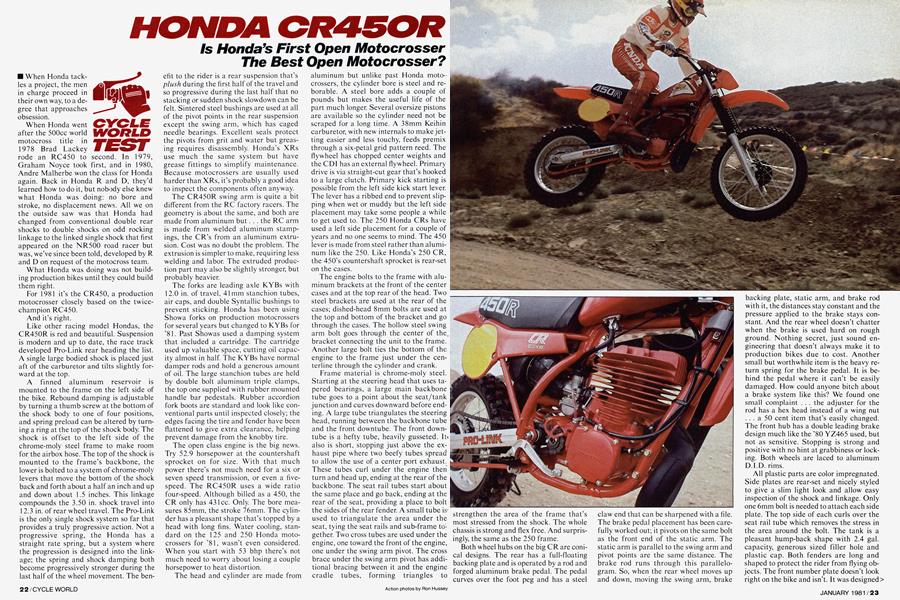

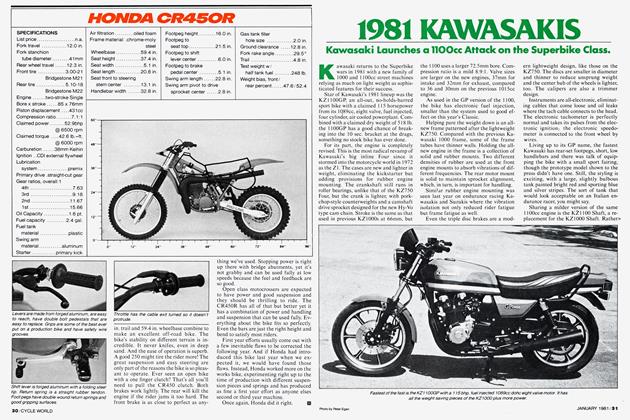

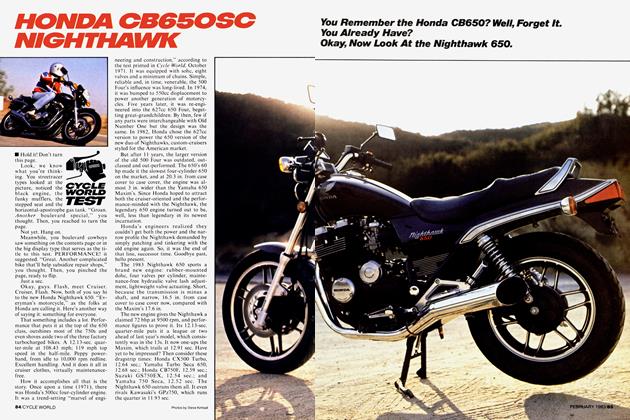

HONDA CR450R

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Is Honda's First Open Motocrosser The Best Open Motorcrosser?

When Honda tackles a project, the men in charge proceed in their own way, to a degree that approaches obsession.

When Honda went after the 500cc world motocross title in 1978 Brad Lackey rode an RC450 to second. In 1979, Graham Noyce took first, and in 1980, Andre Malherbe won the class for Honda again. Back in Honda R and D, they’d learned how to do it, but nobody else knew what Honda was doing: no bore and stroke, no displacement news. All we on the outside saw was that Honda had changed from conventional double rear shocks to double shocks on odd rocking linkage to the linked single shock that first appeared on the NR500 road racer but was, we’ve since been told, developed by R and D on request of the motocross team.

What Honda was doing was not building production bikes until they could build them right.

For 1981 it’s the CR450, a production motocrosser closely based on the twicechampion RC450.

And it’s right.

Like other racing model Hondas, the CR450R is red and beautiful. Suspension is modern and up to date, the race track developed Pro-Link rear heading the list. A single large bodied shock is placed just aft of the carburetor and tilts slightly forward at the top.

A finned aluminum reservoir is mounted to the frame on the left side of the bike. Rebound damping is adjustable by turning a thumb screw at the bottom of the shock body to one of four positions, and spring preload can be altered by turning a ring at the top of the shock body. The shock is offset to the left side of the chrome-moly steel frame to make room for the airbox hose. The top of the shock is mounted to the frame’s backbone, the lower is bolted to a system of chrome-moly levers that move the bottom of the shock back and forth about a half an inch and up and down about 1.5 inches. This linkage compounds the 3.50 in. shock travel into 1 2.3 in. of rear wheel travel. The Pro-Link is the only single shock system so far that provides a truly progressive action. Not a progressive spring, the Honda has a straight rate spring, but a system where the progression is designed into the linkage; the spring and shock damping both become progressively stronger during the last half of the wheel movement. The benefit to the rider is a rear suspension that’s plush during the first half of the travel and so progressive during the last half that no stacking or sudden shock slowdown can be felt. Sintered steel bushings are used at all of the pivot points in the rear suspension except the swing arm, which has caged needle bearings. Excellent seals protect the pivots from grit and water but greasing requires disassembly. Honda’s XRs use much the same system but have grease fittings to simplify maintenance. Because motocrossers are usually used harder than XRs, it’s probably a good idea to inspect the components often anyway.

The CR450R swing arm is quite a bit different from the RC factory racers. The geometry is about the same, and both are made from aluminum but. . . the RC arm is made from welded aluminum stampings, the CR’s from an aluminum extrusion. Cost was no doubt the problem. The extrusion is simpler to make, requiring less welding and labor. The extruded production part may also be slightly stronger, but probably heavier.

The forks are leading axle KYBs with 12.0 in. of travel, 41mm stanchion tubes, air caps, and double Syntallic bushings to prevent sticking. Honda has been using Showa forks on production motocrossers for several years but changed to KYBs for ’81. Past Showas used a damping system that included a cartridge. The cartridge used up valuable space, cutting oil capacity almost in half. The KYBs have normal damper rods and hold a generous amount of oil. The large stanchion tubes are held by double bolt aluminum triple clamps, the top one supplied with rubber mounted handle bar pedestals. Rubber accordion fork boots are standard and look like conventional parts until inspected closely; the edges facing the tire and fender have been flattened to give extra clearance, helping prevent damage from the knobby tire.

The open class engine is the big news. Try 52.9 horsepower at the countershaft sprocket on for size. With that much power there’s not much need for a six or seven speed transmission, or even a fivespeed. The RC450R uses a wide ratio four-speed. Although billed as a 450, the CR only has 431cc. Only. The bore measures 85mm, the stroke 76mm. The cylinder has a pleasant shape that’s topped by a head with long fins. Water cooling, standard on the 125 and 250 Honda motocrossers for ’81, wasn’t even considered. When you start with 53 bhp there’s not much need to worry about losing a couple horsepower to heat distortion.

The head and cylinder are made from aluminum but unlike past Honda motocrossers, the cylinder bore is steel and reborable. A steel bore adds a couple of pounds but makes the useful life of the part much longer. Several oversize pistons are available so the cylinder need not be scraped for a long time. A 38mm Keihin carburetor, with new internals to make jetting easier and less touchy, feeds premix through a six-petal grid pattern reed. The flywheel has chopped center weights and the CDI has an external flywheel. Primary drive is via straight-cut gear that’s hooked to a large clutch. Primary kick starting is possible from the left side kick start lever. The lever has a ribbed end to prevent slipping when wet or muddy but the left side placement may take some people a while to get used to. The 250 Honda CRs have used a left side placement for a couple of years and no one seems to mind. The 450 lever is made from steel rather than aluminum like the 250. Like Honda’s 250 CR, the 450’s countershaft sprocket is rear-set on the cases.

The engine bolts to the frame with aluminum brackets at the front of the center cases and at the top rear of the head. Two steel brackets are used at the rear of the cases; dished-head 8mm bolts are used at the top and bottom of the bracket and go through the cases. The hollow steel swing arm bolt goes through the center of the^ bracket connecting the unit to the frame. Another large bolt ties the bottom of the engine to the frame just under the centerline through the cylinder and crank.

Frame material is chrome-moly steel. Starting at the steering head that uses tapered bearings, a large main backbone tube goes to a point about the seat/tank junction and curves downward before ending. A large tube triangulates the steering head, running between the backbone tube and the front downtube. The front downtube is a hefty tube, heavily gusseted. Iff also is short, stopping just above the exhaust pipe where two beefy tubes spread to allow the use of a center port exhaust. These tubes curl under the engine then turn and head up, ending at the rear of the backbone. The seat rail tubes start about the same place and go back, ending at the rear of the seat, providing a place to bolt the sides of the rear fender. A small tube isused to triangulate the area under the seat, tying the seat rails and sub-frame to1 gether. Two cross tubes are used under the engine, one toward the front of the engine, one under the swing arm pivot. The cross brace under the swing arm pivot has additional bracing between it and the engine cradle tubes, forming triangles to strengthen the area of the frame that’s most stressed from the shock. The whole chassis is strong and flex free. And surprisingly, the same as the 250 frame.

Both wheel hubs on the big CR are conical designs. The rear has a full-floating backing plate and is operated by a rod and forged aluminum brake pedal. The pedal curves over the foot peg and has a steel claw end that can be sharpened with a file. The brake pedal placement has been carefully worked out; it pivots on the same bolt as the front end of the static arm. The static arm is parallel to the swing arm and pivot points are the same distance. The brake rod runs through this parallelogram. So, when the rear wheel moves up and down, moving the swing arm, brake backing plate, static arm, and brake rod with it, the distances stay constant and the pressure applied to the brake stays constant. And the rear wheel doesn’t chatter when the brake is used hard on rough ground. Nothing secret, just sound engineering that doesn’t always make it to production bikes due to cost. Another small but worthwhile item is the heavy return spring for the brake pedal. It is behind the pedal where it can’t be easily damaged. How could anyone bitch about a brake system like this? We found one small complaint . . . the adjuster for the rod has a hex head instead of a wing nut ... a 50 cent item that’s easily changed. The front hub has a double leading brake design much like the ’80 YZ465 used, but not as sensitive. Stopping is strong and positive with no hint at grabbiness or locking. Both wheels are laced to aluminum D.I.D. rims.

All plastic parts are color impregnated. Side plates are rear-set and nicely styled to give a slim light look and allow easy inspection of the shock and linkage. Only one 6mm bolt is needed to attach each side plate. The top side of each curls over the seat rail tube which removes the stress in the area around the bolt. The tank is a pleasant hump-back shape with 2.4 gal. capacity, generous sized filler hole and plastic cap. Both fenders are long and shaped to protect the rider from flying objects. The front number plate doesn’t look right on the bike and isn’t. It was designed> to fit the water-cooled 125 and 250. The large size is a requirement of the AMA for ’81. The placement and screen below let air pass to the radiator on Honda’s water pumpers but looks silly on the air-cooled 450.

The seat on Honda’s newest racer is thicker than past CRs. Not all the way back, just in the area used most: the front. Making the front thick increases rider comfort and doesn’t force the rider forward. The seat base is plastic. Steel mounting brackets are bolted to the base and easily replaced if broken. The seat mounts to the frame with two bolts like most motocrossers. The difference between the CR450R seat and most others is the ease of replacement. The front has a tongue and groove system with the tongue on the frame, not the seat base. The seat base has the groove cast in it and the seat just falls in place, no hassle. The two attaching bolts tap into the frame rail so there’s no fumbling with loose nuts.

Hand controls are first rate: the grips are some of the best in motocross. They are soft with an aggressive pattern, the throttle side fits over a groove on the twist grip, the left side has a groove on its front for safety wire. The throttle is a straightpull design that looks like they took a regular throttle and added a curved cable outlet to it. The cable makes the turn against a plastic rub block and works well. Hand levers are dog-leg shaped and made from forged aluminum then anodized black. They are easy to reach with normal sized hands and work smoothly. Lever pivots are a cap design, meaning the pivot can be replaced without removing the grip or throttle. Control cables are large nylon lined and work smoothly thanks to thoughtful routing. Front brake cable guides have floating plastic blocks and the brackets are designed for easy safety wiring.

The high mounted pipe is made from die-stamped steel parts with a welded seam top and bottom. To ensure the parts don’t separate, small bridges are welded across the seams at stress points and the top seam is bridged the entire length of the plastic tank’s bottom. Bridging under the tank is insurance against a pipe splitting and directing heat toward the plastic tank. The headpipe is large and long, winding around the front of the frame before going up the left side of the bike. The lower front of the headpipe extends below the frame tubing where it’s easily damamged if ridden on rocky terrain. The rest of the design is good: the large cones tuck completely under the tank out of the way, and the rear tucks in nicely since it doesn’t have to go around a shock. Mounting brackets are well designed and placed, the silencer having two, one above, one below. The silencer is small, fairly quiet and nonrepackable.

Race-inspired trickery abounds on the 450. The fuel petcock is mounted so the control lever is pointed in toward the engine, making it impossible to turn off with the rider’s knee while riding: a metal rod is welded to the frame tube just above the brake pedal, precaution against applying pressure to the brake rod with the rider’s heel; the forged aluminum shift lever has a large folding steel end that won’t hurt the rider’s foot, need cover replacement, nor damage the transmission internals if jammed. And the rubber band return spring ensures it’ll return in the muddiest race; the front axle clamp is a four-bolt. design; the chain is a D.I.D. TR; the carburetor is positioned to the right side of the bike where it’s easy to work on; the air cleaner element is foam and the airbox draws air from the top sides, blocks water from entering the front and rear; shock spring preload is easily adjusted using a hammer and punch; shock damping changes are made with one finger; footpegs have small double wound return springs that don’t bind up in mud; the chain guide is made from aluminum and has a plastic roller and rub block; plastic rollers are placed above and below the swing arm pivot to control chain tension during rear wheel movement; the front brake cable has an extra wide cable clamp so the cable won’t flex into the spokes; the countershaft sprocket cover is also a case protector: the coil is mounted on the downtube where air can cool it: swing arm and axle bolts are hollow; the fuel line just below the petcock is formed into a curve so it can’t kink. Attention to detail is incredible.

The CR450R has a 37.4 in. seat height but somehow it feels higher. A six-footer is barely tall enough in riding boots. The high bike and long kick start lever combine to make starting a little clumsy until the rider learns to stand on a rock or berm, any object that’ll get him a little higher above the bike. Some of our riders thought it easier to stand next to the CR and kick the lever with the right foot like Husky manuals suggest. Either way, the bike demands a quick spin of the engine. Anyone used to starting an open motocrosser will find the CR easier than most. One or two swift kicks will do it while hot, almost always two when cold. Warm-up is rapid.

The engine is extremely smooth. A slight vibration can be felt while sitting still, mostly the result of the pipe, but it disappears once under way. Power progression is smooth and totally predictable. No sudden bursts of uncontrollable power, no flat spots, no richness or leaness.

The horsepower is awesome. Yet it’s completely controllable and predictable. Power at lower revs feels less than what the YZ465 makes, but the softer power makes the bike easier to ride. Wheelspin is less and the bike doesn’t try to get sideways in corners with small throttle openings. The short stroke engine winds freely and smoothly all the way to peak, seeming to get even smoother the higher it’s wound.

The four-speed transmission shifts perfectly. It’s smooth, positive and sure. We tried starting in different gears, using a Yamaha YZ465 as a control. Although 2nd gear starts felt fastest, 1st proved better. (Of course the gear chosen will depend on rider ability, weight and terrain.) The bike comes off the line straight and true in either gear. The rider needs to lean on the bars before dropping the clutch or the bike> will come out of the gate with the front wheel too high. Power is so abundant that the wheel is almost impossible to keep on the ground, but acceleration suffers if it is allowed to get too high. The bike doesn’t have to be short shifted like a YZ465. The motor is perfectly happy when winding. Final gear ratios are almost the same as a Yamaha YZ465’s when the Yamaha’s first gear is disregarded. That is, 2nd on the YZ465 is almost the same as 1st on the CR, 15.09 versus 15.66. Second and 3rd on the Honda are almost the same as 3rd and 4th on the Yamaha, and top gear for the Yamaha is 7.18, and 7.63 on the Honda. In a head-to-head drag, the Honda won but our 465 is almost a year old and it’s starting to get a little tired. With both machines in new condition and operated by equal weight riders of equal ability, the difference should be little or none.

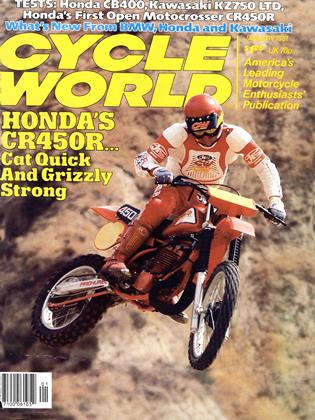

The newest CR from Honda is a delight to ride; it’s the only open class motocrosser we’ve ridden that doesn’t steer and feel like an open bike. Handling is like a 250. Steering is precise and sure. Balance is perfect and the bike changes direction like a good 125. Any corner can be charged into without fear of blowing the turn. Bermed or flat, turns are easy, the bike is the most neutral open bike we’ve tested. The rider never has to fight the machine to get it to go where he wants. Once in the corner, the rider can change his mind and take a different line if a rival falls or an inside or outside line opens up. And going into bumpy whooped corners is no problem. The bike doesn’t try to swap when the brakes are used hard in such corners nor does it dive like most motocrossers. The front will dip but the change in attitude is much less than any MXer we’ve tried. If a square edged hole or lip is encountered when braking hard for a corner, the CR doesn’t kick or do other nasty things, the rear wheel just rolls over the lip, staying on the ground. And the forks work almost as well. Finally, there’s a Honda motocrosser with forks that don’t need modification. The 450 is a fantastic jumper. No jump is too high. Landings are always soft and controlled. One of our testers put the bike completely sideways over a big jump and left it sideways for several consecutive landings, all without mishap! Most bikes would spit the rider over the high side if landed in such a manner. The CR didn’t even whimper with such abuse. Even the sideways landing failed to flex the chassis enough to throw a chain.

We fooled around with different settings on the shock and forks and had no trouble dialing in the suspension for different riders and different tracks. For most motocross tracks we liked the #2 damping setting on the shock, #1 being the lightest setting, #4 the stiffest. Spring preload worked best % in. from the top of the threads to the top of the lock ring. Most of us liked the forks with the stock oil level and weight and 4 to 5 psi air pressure.

Because of the four-speed transmission the big CR isn’t as easily adapted to offroad use, a common use of open motocrossers. We liked the bike best with no air in the forks and the rebound damping set at #1 so the back end could keep up with the bumps at high speeds. The bike works well as an off-road play bike if the rider is an expert or fast amateur. Novices will probably have trouble with the tall low gear on steep rocky hills. The head pipe protrudes below the frame rails several inches so protective bars or straps will have to be welded to the pipe to keep from squashing it closed. We worried about the bike being too quick handling in sandwashes, since it slices through corners on a MX course so quickly, but it proved more stable in deep sand than any leading axle bike we’ve tested. The 29.5 ° fork rake, 4.8 >

HONDA CR450R

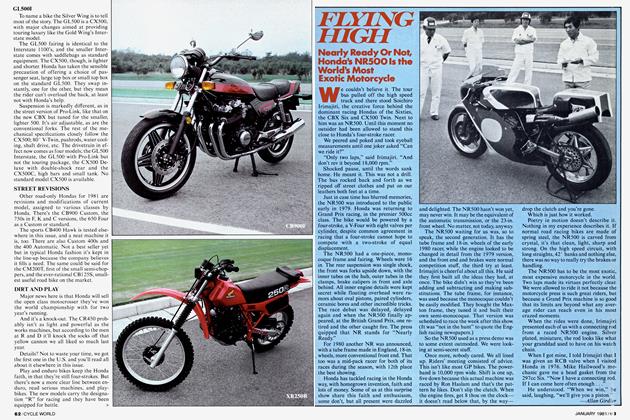

SPECIFICATIONS

in. trail and 59.4 in. wheelbase combine to make an excellent off-road bike. The bike’s stability on different terrain is incredible. It never knifes, even in deep sand. And the ease of operation is superb. A good 250 might tire the rider more! The great suspension and easy steering are only part of the reasons the bike is so pleasant to operate. Ever seen an open bike with a one finger clutch? That’s all you’ll need to pull the CR450 clutch. Both brakes work lightly. The rear will kill the engine if the rider jams it too hard. The front brake is as close to perfect as any-

thing we’ve used. Stopping power is right up there with bridge abutments, yet it’s not grabby and can be used fully at low speeds because the feel and feedback are so good.

Open class motocrossers are expected to have power and good suspension and they should be thrilling to ride. The CR450R has all of that but better yet it has a combination of power and handling and suspension that can be used fully. Everything about the bike fits so perfectly. Even the bars are just the right height and bend to satisfy most riders.

First year efforts usually come out with a few inevitable flaws to be corrected the following year. And if Honda had introduced this bike last year when we exj pected it, we would have found those flaws. Instead, Honda worked more on the works bike, experimenting right up to the time of production with different suspension pieces and springs and has produced as fine a first year effort as anyone elses second or third year machine.

Once again, Honda did it right. E9