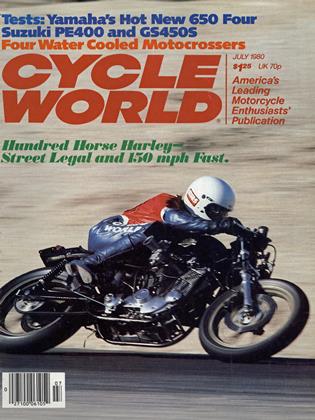

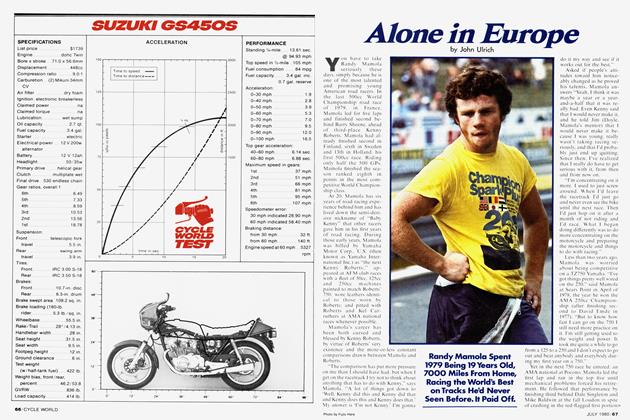

YAMAHA XJ650 MAXIM I

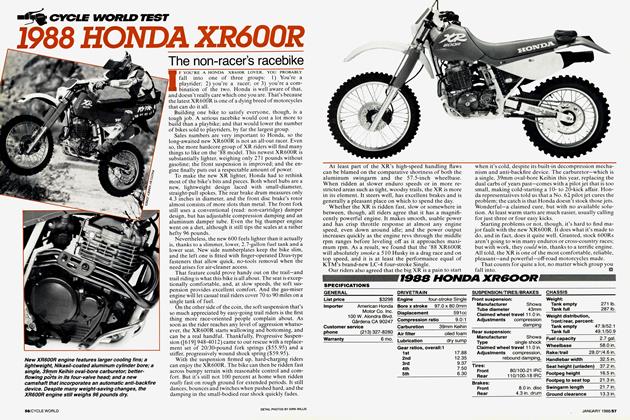

CYCLE WORLD TEST

High-Style, High-Performance Motorcycle Born in Surveys and Focus Groups

Yamaha’s XJ650 Maxim I is an unusual motorcycle. What makes it unusual isn’t its semichopper styling, nor its 12.91 sec. at 103.09 mph quarter-mile time, nor its 57 mpg on the Cycle World mileage test loop. And while the XJ650 is light(470 lb. with half a tank of gas) for its

size and stops very well (requiring 133 ft. from 60 mph) what makes it stand out isn’t found in the machine’s technical specifications or performance capabilities.

What makes this machine stand out from the rest, what makes the Maxim I different from any other motorcycle, is how it came into being.

The usual state of affairs is for a motorcycle manufacturer to envision, develop and build motorcycles, then present prototypes to the top officials of the com-

panies which distribute the machines in overseas markets. Those officials decide which designs they will sell, and request variations of the designs. But the machines remain products of their country of origin, usually Japan.

Yamaha Motor Corp., U.S.A. is the American distributing company for Yamaha motorcycles. Despite its close ties with the factory in Japan, it is a separate concern.

Yamaha Motor Corp. changed the way> Japanese motorcycles come to be sold in this country.

Late in the 1970s, the Yamaha Motor Corp. marketing department, headed by Dennis Stéfani and Rit LeFrancois, determined that the market was ripe for stylized machines with a resemblance to the choppers some enthusiasts built out of stock motorcycles. They suggested that Yamaha manufacture and sell such motorcycles, direct from the factory.

The results were semi-choppers, Yamahas named Specials. They came with bucko-bars, stepped seats, hints of sissy bars, teardrop tanks, fat rear tires.

They sold like crazy. Other companies scurried to emulate Yamaha’s styling coup. But even as the other companies took their first timid steps into semi-chopper-hood, Yamaha pressed the outside edges of the known marketing world. Specials stood out in a changed marketplace where what used to be the standard models—bikes that looked like motorcycles did before the semi-choppers took over—became the exceptions to the majority of stylized models.

Midnight Specials were introduced for 1980, dripping black chrome and black paint and gold trim, taking the art of transforming motorcycles into Specials to the limit.

The next step was to build a Special from the ground up, to the American company’s marketing department specifications.

That Special is the XJ650.

The Maxim I.

That the machine would be a Special

was decided long before the American marketeers brought their findings to the Japanese engineers in August of 1978. The demand for Special styling had already been proven. Motorcyclists recruited for focus groups were paid to look at motorcycle design concepts and register their responses. Using acetate overlays of chassis, tanks, seats, engines, w heels, exhaust systems, people in the groups were able to “design” their ideal motorcycle.

The focus groups and a battery of surveys brought answers.

The bike the majority of people wanted to buy must look comfortable. The seating position must look natural, and easy to control the machine from. None of this crouched over the bars, no sir. But sitting upright, just like on a park bench? Great. Nice. wide, low seat to get the feet on the ground at a stop; forward-placed footpegs to maintain the position when rolling; pull-back bars to keep the back straight— there you've got it.

More answers. Name the three most important things you look for in a motorcycle. asked another survey.

Easy, came the reply.

1. Reliability.

2. Styling.

3. Performance.

More questions. More responses. The people want four-strokes. Just like that stone-reliable Chevy parked in front of the house. No problem, starts right up. takes you where you want to go.

Don't want a kickstarter. If it's got a kickstarter, it must not have a reliable electrical system. Chevys don't come with

hand cranks, now do they? The people want something that starts right up. no kicking, no pushing. Reliable.

Got to look nice. Smooth, round. Not square. Nice flow. Stylish.

But the thing has still got to be reliable and easy to “operate.'” said the surveys, so the ideal Special can't give up needed features or function for styling. Compromise must be eliminated. It’s got to be a Special from the drawing board forward, because the people want:

Performance.

Everybody wants styling, and everybody wants performance. The largest group in one survey put performance at the top of their list of most important factors in deciding to buy a motorcycle—not just reasonable performance, but super performance. XS11 type, demanded above all other considerations by 25 per cent of the people surveyed in this case. (Quiet and smooth engine drew 24 per cent; cost 18 per cent; commuting and cruising adaptability 14 per cent; uniqueness 9 per cent.)

Away from the groups of people, and into hard sales figures, the strategy was shaping up. How big should the ideal marketeer’s Special be?

The team of researchers looked at the 750cc class. They considered the 500-599cc range.

The 500-599cc class was too small, thev concluded, and couldn't compete with existing competitive 650 and 750cc motorcycles. But 750s cost more to buy and insure.

More important, the trend for sales in the 450-599cc size bracket was downward. In 1976. 67.289 machines ofthat size range were sold, taking 27.9 per cent of the total American motorcycle market. But that dropped to 59.490 bikes of that size in 1979. just 16.6 per cent of the market.

But 600-699cc? Up from 19.001 (7.8 per cent) in 1976 to a whopping 64.308 ( 18 per cent) in 1979. largely on the broad back of the popular Kawasaki KZ650.

The KZ650 Four was introduced for the 1977 model year. In 1976. the best selling 650cc machine available in America was the Yamaha XS650 Twin. In 1977. after the introduction of the KZ650. 600-699cc class sales doubled to 40.786 machines, and the numbers jumped each succeeding vear.

The sales figures showed the growth in interest and sales of a 650. The surveys reflected the buying public's desire for performance, spelled horsepower.

The new Special w'ould be a 650cc four stroke, dohc Four, an engine configuration which exemplified performance for motorcyclists in a way a V-Eight meant performance for car buyers of happier, no-gasshortage automotive days.

Goals were set. Not only would the newmachine be styled as a Special, it would also be the lightest and fastest performance motorcycle in its class.

And it would have a name, reflecting the motorcycle's unique birth and personality.

It wouldn’t just be another Special.

It would be the Maxim I.

Maxim I.

That’s all the side panels say. Not “XJ650.” Not “650 Special.”

Maxim I.

Funny. Sounds like the name of some sort of liberated woman’s cigarette. “Get low tar, taste and ERA-era sophistication with new, slim Maxim I imported cigarettes.”

But the bike doesn’t look like a machine designed by focus groups and surveys and marketeers and even, God forbid, men in pale green Yamaha coats running around feeding numbers into a computer in Iwata, Japan.

It doesn’t look like a horse designed by committee, a camel.

It looks just like what it is, a machine built to force anybody susceptible to the image of Specials to reach for his credit application and make the plunge.

Low. Lean. Stylish.

Even the engine fins are trimmed here, lengthened there to shape the cylinders and head, to contribute to the lines of the bike. The tank arches rearward in more of a teardrop shape than any teardrop we’ve seen before. The seat is oh so low, the frame rails curved and styled to blend with the overall effect. No style pasted on this baby. This thing is style from its essence. No frame with sidecovers creating a custom look. Instead, a Special frame.

Even a Special engine.

It starts conventionally enough, 653cc 63 X 52.4mm bore and stroke, dohc with cam drive off the plain-bearing crankshaft by a roller chain. Two valves per cylinder, 33mm intake and 28mm exhaust. Cam timing is measured from and to 0.3mm on the exhaust cam and 0.25mm on the intake cam. The intake valves open at 34° BTDC and close at 58° ABDC, while the exhaust valves open at 66° BBDC and close at 26° ATDC, Duration is 272° for both intake> and exhaust. Intake lift is 8.25mm. exhaust lift 7.5mm. Compression ratio is 9.5:1.

Ignition is electronic, without points. Carburetion. a bank of four 32mm Hitachi CVs. Starting is by electric motor only, no kick. Primary drive is straight-cut gear. Final drive is by shaft.

To give the Maxim 1 a low', low’ seat height of 29.5 in., the engine had to be carried relatively close to the ground. Normally, the lower an engine is mounted, the sooner its sidecases or auxiliary covers drag when the bike is leaned into a turn and the less cornering clearance it has.

Performance machines aren't supposed to drag everything in sight at the first hint of a corner, and the Maxim is supposed to be a performance machine. The people wanted a low seat and performance both. Yet performance dictated a Four, which limited how narrow7 the engine could be.

And to maintain the seating position preferred by the people participating in the focus groups, the footpegs would have to be mounted well forward. With most engines, positioning the pegs so far forward (relative to the crankshaft) would leave the rider's toes hitting the crankshaft-mounted alternator.

So the engineers took the alternator off the usual place—the end of the crankshaft—and mounted it on an auxiliary shaft behind the cylinders, driving that shaft off the crankshaft via a Hy-Vo type silent link-plate chain. Now the engine was just 17.6 in. wide at its broadest point. (For comparison, the XS650 Twin’s engine is 15 in. wide; the GS550 Suzuki has 21 in. of case width; the Kawasaki KZ650, 21 in.; the Honda CB650, 20.3 in.)

Now’ that the engine width problem was solved, any reasonable attempt to tuck in the exhaust system would give the bike the cornering clearance it needed for performance riding, without sacrificing the low seat.

What about weight? The Maxim engine weighs 200.2 lb. dry, compared to 210.4 lb. for the KZ650 motor and 203.5 lb. for the Suzuki GS550 powerplant.

To save weight in the engine package. Yamaha engineers used a ferrite magnet for the starter motor; a compact A.C. generator with graphite brushes; and an electronic ignition advance system. Determined to retain a minimal-maintenance driveshaft for final drive, the engineers eliminated the transmission lay shaft and middle gear box, reducing the number of parts involved in and simplifying the flow of power from crankshaft to rear w heel.

Weight saving efforts extended to the chassis. Plastic is used where possible: for the seat base pan. the battery box, the chrome emblem plate on the lower triple clamp. Bolts that normally serve one purpose do double duty. The rear engine mount bolt, for example, also secures both footpegs. The centerstand, instead of riding on a conventional long pivot tube, is secured to two lightweight mount plates by bolts, pivoting on short tube collars extending from one side of each mount plate.

The biggest weight saving comes from not over-designing. Using a stress analysis computer program developed in the NASA space program, Yamaha engineers determined exactly how’ strong major components—such as cast wheels—had to be, then made them just that strong. The frame carries no extra gussets "just in case.’’ and isn’t any thicker or heavier than it has to be. It is exactly as strong as it must be to handle the stresses it is subjected to. Which has a lot to do with w hy the Maxim I—with driveshaft and cast wheels—weighs 470 lb. w ith gas, compared to 466 lb. for a wire spoke-wheeled GS550. 493 lb. for a wire spoke-w heeled KZ650 and 474 lb. for a Honda CB650. The standard, spokewheeled Yamaha XS650 Twin weighs 481 lb. Of the bikes mentioned, only the Yamaha Maxim 1 has shaft drive.

Everybody w ho has been around motorcycles has heard the advantages touted for shaft drive versus chain drive. Shafts, after all. are cleaner, require less attention, are unaffected by rain and just about never fail. But chain drive, says common knowledge. is more efficient in transmitting power.

Wrong, say the Yamaha engineers. Their research, comparing the shaft drive system used in the Maxim I with the chain drive of the XT500, shows that the shaft system transmits 95 per cent of the power it receives, while the properly-lubricated chain drive system of the XT500 transmits 90 per cent of the power fed into it.

Chain drive does retain advantages, however, namely weight, cost and lack of negative effect on handling. In the case of the Maxim I. the decision to use a driveshaft added 1 1 lb. and about $150 to the retail price. As for the handling, one Yamaha official told reporters that he supports a change in Superbike Production displacement limits down to 750cc, in which case Yamaha will build racebikes based on the Maxim I and prove that a shaft drive Four can win against chaindrive Fours. . . .

Along with the driveshaft. Yamaha engineers paid special attention to gear engagement dog freeplay and the clutch actuating system. In fifth gear, the Maxim I has just 2° of free play between engagement dogs, compared to the XS750's 10°. That means the Maxim rider feels less drive line snatch between closing the throttle and reopening it. T he other gear sets on the Maxim transmission have more freeplay in the engagement dogs, because the engineers envisioned the Maxim being used for sporting riding, and reducing the freeplay inhibits fast shifts. So second, third and fourth gears have 29° of freeplay. while first has 36°.

The clutch is conventional, eight driven and eight drive plates, in an oil supply shared with the crankcase and the transmission. But unlike some four-stroke Yamahas, the Maxim has a needle roller throwout bearing instead of a bronze bushing. avoiding the squall heard, for example. from an XS650 w hen the clutch is first pulled in after a cold start. And the clutch has rack and pinion actuation, saving weight and in theory making clutch release more precise and accurate.

What the Maxim I does not have is a bulletproof clutch.

It isn't as prone to quick-start swelling and permanent engagement as the XS850 clutch, but the Maxim clutch comes nowhere near the indestructable nature of Kawasaki clutches. The first clutch in our test bike had been modified—without our knowledge—by Yamaha service personnel to counteract what they considered an objectionable chatter upon cold start. The modification consisted of sanding the metal plates with fine sandpaper.

The clutch didn't chatter but the barest attempt at a quick getaway—even at moderate rpm—from a stop sign left the clutch reluctant to disengage fully. Shifting became notchy and imprecise, requiring a lot of shift lever pressure. Free travel at the clutch disappeared.

The clutch got worse and worse until it finally would not disengage at all, locking the Maxim I in fourth gear (remember the close gear engagement dog tolerances for fifth gear?) on attempts to shift up through the gears. Slamming into lower gears without trying to use the clutch was still possible, but difficult. The last straw, evidently, had been a fast, maximum-rpm start at the road race course used to test the Maxim's high-speed handling (but more on that later).

At the drag strip, a new clutch was installed—without any sanding of the metal plates—and suddenly the Maxim would shift easily again. It took more than six hard passes before the Maxim had reached its best time—12.91 sec. at 103.09 mph—and the clutch had started to resist disengaging. This time the symptoms were less acute—the bike just didn't shift as easily and predicting the exact point of clutch engagement off the line was impossible.

Still, that best time of 12.91 makes the Maxim I the quickest 650cc motorcycle this magazine has tested. Whatever else it is, the Maxim I is definitely a performance motorcycle.

That doesn't mean that it’s the 650 class machine we’d prefer to ride on the street. The Kawasaki KZ650 for instance, while slower at the dragstrip. has the kind of mid-range punch that makes riding a street bike enjoyable in real life situations—midrange punch that doesn’t show up in E.T. figures, mid-range punch that the Maxim I lacks.

The Maxim runs well enough at lower rpm. It’s just that it makes its best power over 5000 rpm. and nothing much exciting happens below that. One staffer compared the free-revving engine to the late, great CB400F Honda. Ridden in 400F mode— i.e. damn the road speed, gimme more revs—the Maxim scoots right along. But the Kawasaki KZ650 will kill it in a roll-on, in traffic jams when a slot in the next lane suddenly opens up, or coming off corners at the road race course.

That’s right. Road race course. The Maxim’s a performance bike, right? Right. So we took it where we take all performance bikes—the racetrack.

The occasion was an American Road> Race Assn. (ARRA) meet at Ontario Motor Speedway in Southern California. The man in charge of tech inspection summed up the reaction of onlookers.

“Get this guy out of here.” he said, laughing as he surveyed the Maxim’s stock bucko-bars and safety-wired-on number plates. “This guy doesn't need tech inspection. He needs a psychiatrist.”

The laughing only died a little when the Maxim lurched off the line in a mixed class race for the start of a mid-pack battle with two TZ250s, a hopped-up Yamaha 500 Single in GP trim and a box stock KZ750 Four. Lap after lap the XJ was passed on the straight, only to repass in the esses and on the brakes, grinding and scraping along the w'ay. Besides proving that the rider was fearless—before the Maxim locked itself in fourth gear and pitted halfway through the race—certain points about its handling became clear.

First, the Maxim can be ridden hard and fast within its limits, which are dictated solely by ground clearance. Despite the best efforts of the engineers, the Maxim grinds the pegs and the exhaust system junctions on both sides, as well as the tip of the right hand muffler. For being as low as it is, it has lots of clearance, plenty for the road (although on the street, the centerstand drags on the left; road racing rules require removing the stands). But before the Maxim runs out of tire it's sending a clear message back to the pilot—one more degree of lean and you’ve had it.

The cure is lots of hanging off, but the low seat actually hampers that as it doesn't leave enough room between seat surface and road at full lean to fit in an adult body hanging off with knee fully extended.

The Maxim does handle. The tires, even the bulbous 16-incher on the back, are well suited to the machine's speed capabilities. The suspension, adjustable only to the extent of selecting rear shock spring preload, functions well at speed (with the shock preload on full). The leading-axle forks don’t flex in esses or delay steering inputs w hile slop is taken up. The motorcycle changes direction where the rider wants, when he wants.

The only tricky part is due to the shaft, which like most shaft drives, raises and lowers the rear end of the bike according to what the rider does with the throttle.

Barrel into a turn too hot and slam the throttle shut and the Maxim sinks in the rear, reducing cornering clearance. Do that when you're already at full lean and it's trouble.

But adjust your riding style to brake hard with the clutch in or at least with neutral throttle and then power around and out of the turn, and you’re fine. It's hard to just jump on and make the necessary transition from chain to shaft drive— and thus keep the bike on a smooth and even keel in the corners but it can be done.

Perhaps just as hard is to learn to buzz the engine coming off the turns, because anything less doesn’t produce the needed drive.

Back on the freeway with the shocks returned to minimum preload, the Maxim's suspension does a reasonable job of soaking up small, repetitive bumps— considering that it also works in the maximum sporting, tear-around-corners mode. Judged for freeway compliance alone, it is too stiff. Because the engine is rubber mounted. vibration isn't noticeable.

The seating position, the subject of much effort by the engineers and touted as being the ultimate, is the ultimate . . . failure. Nobody on the staff liked it. but maybe that's because everybody on the staff of this magazine likes to use motorcycles to go places. For example, one editor lives 45 miles from the offices, and commuted on the Maxim for several weeks. The first day had his forearms and wrists sore as he discovered muscles not normally used riding a conventional motorcycle: his personal bikes sport low bars, not pullbacks. After 20 miles, he reported, he hated the seat—he couldn't move around on it enough to vary position. Didn’t like the peg placement, either.

Nobody else liked it any better. “I found it fine in town, the low seat height, the light weight, great for puttering through rush hour traffic,” said one rider. “I could take the seat for an hour, but the bars are wrong. 1 plainly can't ride this thing in a serious manner.”

Another posed the question “Why make the narrow engine and power for a bike that’s good for short hops, Sunday half hours, 10 miles to work and back?”

Hard to say. But the part about short hops is right, as we found to our dismay that in a mix of freeway and spirited backroad riding the Maxim would demand reserve at 115-125 mile intervals, clearly not enough range in this day of open gas stations often being few’ and far between when you need them most—like during an evening return from a ride.

The problem, of course, is that large gasoline capacity doesn't look as good, as sleek and sculptured, as does just enough gas to be almost acceptable.

Luckily, ridden at speeds close to the posted limits (i.e., sedately) the Maxim will return almost 60 mpg. Lots of the credit for that goes to the Hitachi carbure-' tors, which provide instant, no-hassle cold starts and none of the reluctance Mikunis have to hold a steady speed in low road speed, constant throttle situations. Remarkably. this Yamaha is one of the best motorcycles available in terms of driveability, yet resorts to no technical trickery to meet EPA standards; no unusual combustion chamber shapes, no after-burner systems, not even an accelerator pump to overcome leanness off idle. Yet the Maxim meets the standards, and doesn't make the rider pay for that compliance with niggling carburetion faults or inaccurate throttle response.

The controls are just fine and the choke lever exceptional. It is mounted at thumb's reach on the left handlebar control module. easy to work and adjust. There is one thing about the choke, though. It’s really an enrichment circuit, and while it aides, cold weather starting, it can flood out the engine if left on all the way to the first hard stop. Give the bike full choke, fire it up, ride down the street and slam on the brakes at an intersection 100 yards away, and the engine will die. Flooded. Going easy on the brakes for a mile or two will avoid that.

Mounted up with the easy-to-read, welllit instruments is an oil level warning light. Yeah, level. A small float assembly in the sump is connected to the warning light system, and if oil level drops too low. the light comes on. That way, if somebody who isn't much in tune with mechanics buys a Maxim, and just, say, forgets to ever check the oil level, then the light will w’arn him to do so before the engine frags itself.

Showing the Maxim's cylinder head to some riders not prone to forgetting about checking the oil, in fact some hardcore hop-up freaks, brought ooohs and aaahs of approval. There’s plenty of room in the head for 35mm intake valves, pointed out one. as long as the exhaust valve seat was sunk a bit. Plenty of beef, agreed another. It's a minature XS11, said a third.

As for the styling, it didn't bother them a bit as they fingered calipers and calculators, and scoped out the cylinder head. “This baby can be made to fly,” exclaimed one. They could see what potential the engine had, and didn't care what the rest of the bike was like.

Which kind of makes a mockery of all that research. Research and surveys and focus groups not withstanding, motorcycles are machines and the XJ650 is a good one. Too bad the form overshadows the function.

YAMAHA

XJ65O MAXIM I

$2799

SPECIFICATIONS

ACCELERATION

PERFORMANCE