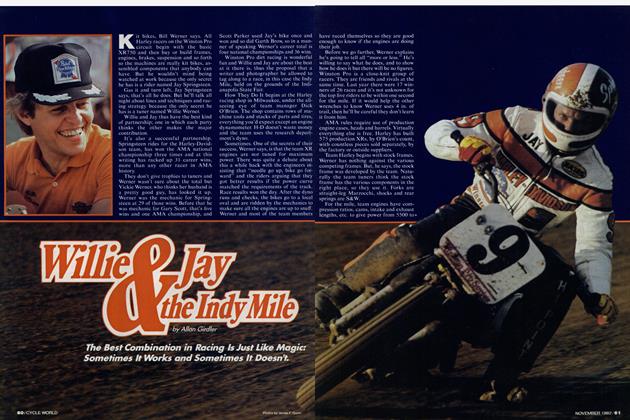

TRIALS REVISITED

COMPETITION

How to be Humble in Three Easy Lessons

Steve Kimball

Lesson One: Playing trials rider is nothing like being a trials rider. What would seem an easy lesson to learn can only be learned by a) playing trials rider and b) being a trials rider. Now. Everybody who’s ever ridden a dirt bike has at one time or another played trials rider. You know, ride the bike out of the truck on the loading ramp, climb over the huge log and see how tight you can make the bike turn. I’m as guilty as the next guy.

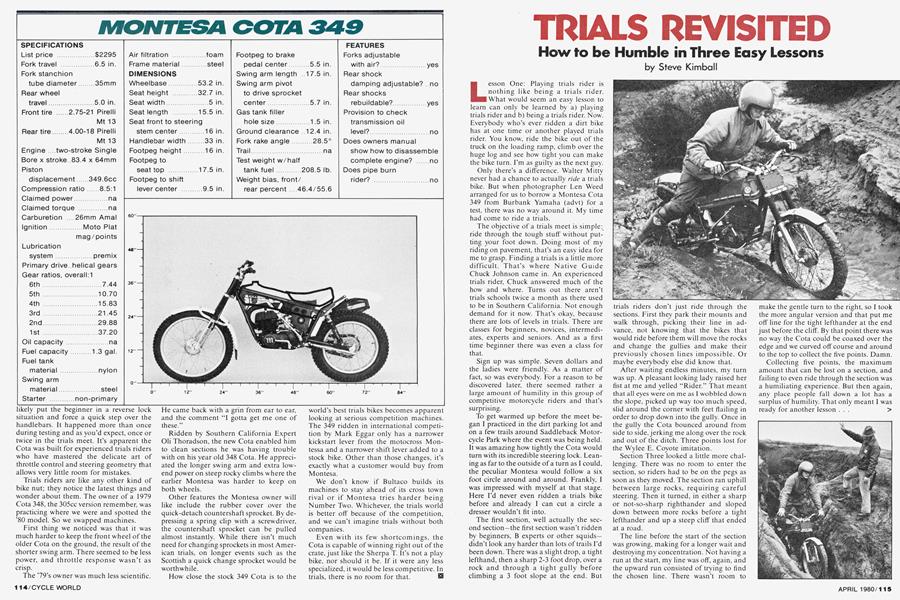

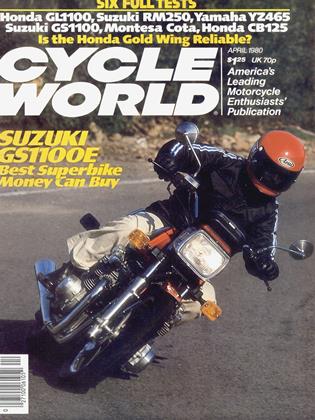

Only there’s a difference. Walter Mitty never had a chance to actually ride a trials bike. But when photographer Len Weed arranged for us to borrow a Montesa Cota 349 from Burbank Yamaha (advt) for a test, there was no way around it. My time had come to ride a trials.

The objective of a trials meet is simple: ride through the tough stuff without putting your foot down. Doing most of my riding on pavement, that’s an easy idea for me to grasp. Finding a trials is a little more difficult. That’s where Native Guide Chuck Johnson came in. An experienced trials rider, Chuck answered much of the how and where. Turns out there aren’t trials schools twice a month as there used to be in Southern California. Not enough demand for it now. That’s okay, because there are lots of levels in trials. There are classes for beginners, novices, intermediates, experts and seniors. And as a first time beginner there was even a class for that.

Sign up was simple. Seven dollars and the ladies were friendly. As a matter of fact, so was everybody. For a reason to be discovered later, there seemed rather a large amount of humility in this group of competitive motorcycle riders and that’s surprising.

To get warmed up before the meet began I practiced in the dirt parking lot and on a few trails around Saddleback Motorcycle Park where the event was being held. It was amazing how tightly the Cota would turn with its incredible steering lock. Leaning as far to the outside of a turn as I could, the peculiar Montesa would follow a six foot circle around and around. Frankly, I was impressed with myself at that stage. Here I’d never even ridden a trials bike before and already I can cut a circle a dresser wouldn’t fit into. The first section, well actually the second section—the first section wasn’t ridden by beginners, B experts or other squids— didn’t look any harder than lots of trails I’d been down. There was a slight drop, a tight lefthand, then a sharp 2-3 foot drop, over a rock and through a tight gully before climbing a 3 foot slope at the end. But trials riders don’t just ride through the sections. First they park their mounts and walk through, picking their line in advance, not knowing that the bikes that would ride before them will move the rocks and change the gullies and make their previously chosen lines impossible. Or maybe everybody else did know that.

After waiting endless minutes, my turn was up. A pleasant looking lady raised her fist at me and yelled “Rider.” That meant that all eyes were on me as I wobbled down the slope, picked up way too much speed, slid around the corner with feet flailing in order to drop down into the gully. Once in the gully the Cota bounced around from side to side, jerking me along over the rock and out of the ditch. Three points lost for the Wylee E. Coyote imitation.

Section Three looked a little more challenging. There was no room to enter the section, so riders had to be on the pegs as soon as they moved. The section ran uphill between large rocks, requiring careful steering. Then it turned, in either a sharp or not-so-sharp righthander and sloped down between more rocks before a tight lefthander and up a steep cliff that ended at a road.

The line before the start of the section was growing, making for a longer wait and destroying my concentration. Not having a run at the start, my line was off, again, and the upward run consisted of trying to find the chosen line. There wasn’t room to make the gentle turn to the right, so I took the more angular version and that put me off line for the tight lefthander at the end just before the cliff. By that point there was no way the Cota could be coaxed over the edge and we curved off course and around to the top to collect the five points. Damn.

Collecting five points, the maximum amount that can be lost on a section, and failing to even ride through the section was a humiliating experience. But then again, any place people fall down a lot has a surplus of humility. That only meant I was ready for another lesson ...

Lesson Two: The only thing worse than putting your foot down in trials is putting your head down. Section Four was a hero section. Lots of big boulders, always boulders, a deceptive downhill, sharp turn at the bottom and a tiny path between two rocks that formed a plateau at the finish.

We all know the scene. With heroic skill and daring the handsome rider carefully picks his way over mountainous boulders and through impossible gullies, making Uturns in foot-wide canyons between rocks. In order to clean the section he must thrust the front axle of his trusty steed upward into the sky, past the finishing markers and then fall crashing into the Grand Canyon below, having given his all to win the Championship.

Sorry folks, but that ain’t what happens. Instead, Our Hero wobbles through the section, missing his line (again!), going over the rocks he was supposed to go around. He picks up way too much speed on a grassy downhill, slides around the turn at the end and lofts the front wheel towards the finishing marker, just putting the axle over the line before tumbling off the plateau and crashing down into a pile of rocks. Fortunately he lands on his head, cushioning the fall. His head bounces two feet back up off a rock, where he catches the rebound and collapses under the politely idling upsidedown Montesa.

The assembled masses, meaning Chuck and friend Pete, everyone else having a good laugh, rush over to see if there’s a Smuckers label on the front of the helmet.

There isn’t. Lesson learned, Our Hero pledges never to go trials riding without a good helmet. Did make it through with only one point lost, though.

Casualty count turned up a bruised shoulder and a bent thumb on the rider and a bent throttle mechanism on the Montesa. Before the meet all the trials riders ooohed and ahhhhed over the straight-pull throttle with the easy disconnect throttle cable. So smooth and direct, everyone said. Thorough testing revealed that when the Montesa’s throttle was brought into contact with a downhill landing the plastic top bent open and 3 oz. of dirt and gravel filled the throttle, sharing the space with the nylon gears and grease. Just like a Harley, I said, noting that the throttle required effort from the rider to both open and close. A lot of effort. Some heavy breathing and a little gas splashed on the mechanism knocked out most of the trespassing dirt and the throttle would turn, but the return spring still couldn’t cope with the demands and the rider had to help.

By now we had learned to put the Cota in line for the next section even before we were ready, so as to cut down on the mind numbing wait. The throttle had been worked on as we waited in line for sections Five and Six, both of them being run together.

Like the Phoenix, the best performance of the day came immediately after the crash. Section Five had a short-but-steep downhill followed by an uphill off-camber slippery turn and then a gully. Section Six followed the gully and turned sharply out of the gully.

Both the downhill and the turn took care of themselves, really, the Cota having more knowledge about this stuff than I. Before I knew it, Section Five was cleaned, my first perfect score of the day, and I was in the next section, putting my foot down once more before leaping out of the ditch. Maybe hope does rise from despair.

More uphills, downhills, tight off-camber turns on grassy slopes and, mostly, rocks made up the last four sections. One was cleaned, another fived due to an excursion on the expert section by mistake and the others added a couple of points.

One loop down and the day was half over. Should be just enough time for another loop, I thought. By this time the lines were shorter as more riders spread out over the 10 sections. The wait was only a few minutes and there was less time to lose concentration. Beginning at Section Two, my score went from a three to a one and I was in control again. The following section was even better as the Cota and I made all the right moves on the right line and we leaped up the cliff at the end and stopped by the marker so he could punch the zero on the score card. Wrong. After going up the cliff the course went five more feet and I had stopped just before the trampled end markers, losing another five points in the process.

Thoroughly deflated, I was ready for . . .

Lesson Three: Not everybody is a trials rider. Strange that this never occurred to me before. Here trials meets keep getting less common and the trials riders I talked to were telling me how much fun they had riding an enduro last week.

When people discovered trials in this country about a decade ago, it was a new fun game. Absent experience and experts, all sorts of dirt riders brought out all sorts of dirt bikes and rode around and had fun. An average guy could take out his DT-1 and go home feeling good, if tired.

Then the bikes and riders got good. Really good. All the big motorcycle manufacturers made trials bikes, though very few of them sold trials bikes. What we got was specialization. A trials bike is every bit as specialized as a motocross bike, in its own peculiar way. It isn’t any good for anything but trials and some of them aren’t all that good for that. Then too, there are guys like Bernie Schreiber, well not quite like him, but they are good. Good enough the courses have to be made tough enough so Bernie can lose a few points, maybe even fall down every now and then.

Back at my old nemesis, Section Four, I thought about that. Afterwards. I didn’t even get to the end, this time, before crashing. The front end of the bike just washed out going down the grassy slope and the Cota, like a playful kitten, jumped on top of me as I closely studied the soil sample.

Exhausted, I slithered out from under the kitten and did another casualty count. This time the left arm felt worse than the right shoulder and the bent thumb was bent-er. Using a perverted logic, I wished that the Montesa was in worse shape. Then it would be its fault if we couldn’t continue.

Actually, none of the Cota’s ills appeared caused by the latest tumble. The shocks had puked their entire contents of shock oil. But then who needs shocks for trials? The throttle was in no worse, if no better, condition and still needed a push in both directions. There was also an odd rattle when the handlebars were turned. Even moving the bike caused the rattle. This was strange. The steering head seemed fine, the clamps were straight and so were the bars—sort of. Then Pete and I saw it: the spokes were so loose they were rattling in their holes.

This was almost the excuse I needed. The wheel really was too loose to steer properly, and neither Pete nor adopted partner and fellow beginner Kenny Norton nor I had a spoke wrench with us. If only the next two sections hadn’t been so easy, it would have been easy to quit now.

Nothing works better to clear the brain than a pleasant little trail ride. So Pete and I wound our way back towards the truck, ostensibly to tighten the spokes and return. We picked gentle trails, the kind that give a rider confidence and time to look around and enjoy himself. We stopped at difficult obstacles and noted how a trials rider could clean them.

Back at the truck I had a very clear head. Without comment, I found the spoke wrench and began. Took four times around the wheel to get the spokes tightened up and not too off-balance. Then it was done. I was ready.

The Cota went back into the truck, its score card returned to the scoring ladies, my tail tucked gently between my legs and we drove slowly home, lessons learned.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue