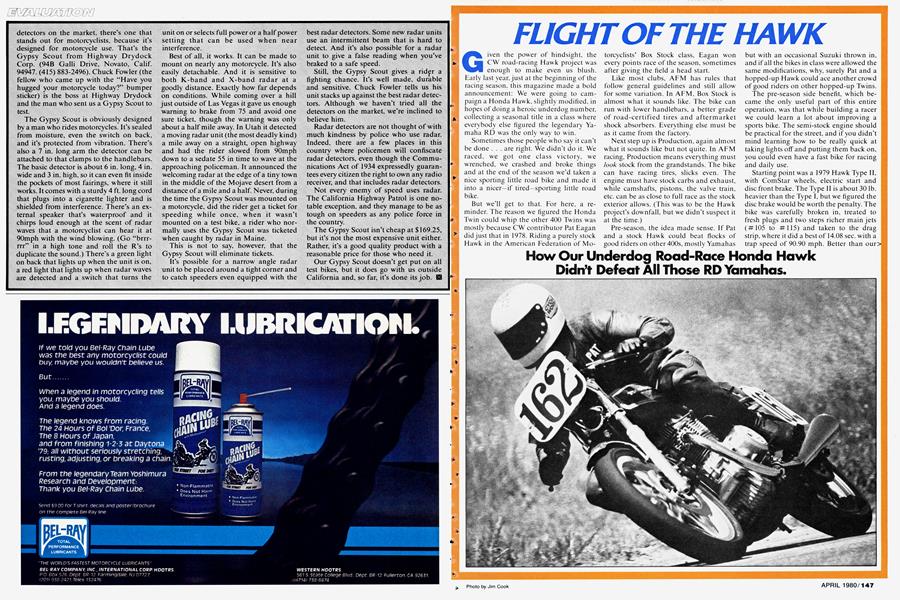

FLIGHT OF THE HAWK

COMPETITION

How Our Underdog Road-Race Honda Hawk Didn’t Defeat All Those RD Yamahas.

Given the power of hindsight, the CW road-racing Hawk project was enough to make even us blush.

Early last year, just at the beginning of the racing season, this magazine made a bold announcement: We were going to campaign a Honda Hawk, slightly modified, in hopes of doing a heroic underdog number, collecting a seasonal title in a class where everybody else figured the legendary Yamaha RD was the only way to win.

Sometimes those people who say it can't be done . . . are right. We didn’t do it. We raced, we got one class victory, we wrenched, we crashed and broke things and at the end of the season we'd taken a nice sporting little road bike and made it into a nicer—if tired—sporting little road bike.

But we’ll get to that. For here, a reminder. The reason we figured the Honda Twin could whip the other 400 Twins was mostly because CW contributor Pat Eagan did just that in 1978. Riding a purely stock Hawk in the American Federation of Motorcyclists’ Box Stock class, Eagan won every points race of the season, sometimes after giving the field a head start.

Like most clubs, AFM has rules that follow general guidelines and still allow for some variation. In AFM. Box Stock is almost what it sounds like. The bike can run with lower handlebars, a better grade of road-certified tires and aftermarket shock absorbers. Everything else must be as it came from the factory.

Next step up is Production, again almost what it sounds like but not quite. In AFM racing. Production means everything must look stock from the grandstands. The bike can have racing tires, slicks even. The engine must have stock carbs and exhaust, while camshafts, pistons, the valve train, etc. can be as close to full race as the stock exterior allows. (This was to be the Hawk project’s downfall, but we didn't suspect it at the time.)

Pre-season, the idea made sense. If Pat and a stock Hawk could beat flocks of good riders on other 400s, mostly Yamahas but with an occasional Suzuki thrown in, and if all the bikes in class were allowed the same modifications, why, surely Pat and a hopped-up Hawk could ace another crowd of good riders on other hopped-up Twins.

The pre-season side benefit, which became the only useful part of this entire operation, was that while building a racer we could learn a lot about improving a sports bike. The semi-stock engine should be practical for the street, and if you didn’t mind learning how to be really quick at taking lights off and putting them back on. you could even have a fast bike for racing and daily use.

Starting point was a 1979 Hawk Type II, with ComStar wheels, electric start and disc front brake. The Type II is about 30 lb. heavier than the Type I, but we figured the disc brake would be worth the penalty. The bike was carefully broken in, treated to fresh plugs and two steps richer main jets (#105 to #115) and taken to the drag strip, where it did a best of 14.08 sec. with a trap speed of 90.90 mph. Better than our previous test Hawk, comparable to the RD400.

But not enough. Road racers run at the drags, or more properly they tune at the drags, just as we were doing, so we knew the top RDs in class would do about 13 sec. and 100 mph.

Then we began to learn the hard way. Jerry Branch, of Branch Flowmetrics, tested the cylinder head. Honda did a good job, he reported, and the ports, valves, etc., moved as much air as the engine could be expected to need, considering that the carbs and exhaust had to be stock. Branch cleaned the passages and polished the valves and the walls of the combustion chamber. With the improved head, the larger jets and a Mega Cycle camshaft—one of two we could find for the Hawk engine, another problem discovered in mid-season—we could barely crack 14 sec. and we’d lost 5 mph through the traps.

Why? Apparently because the better breathing inside didn’t work with the stock parts on the outside. With a stock head, though, and using the new camshaft and the #115 main jets, the Hawk ran the quarter mile in 13.68 sec. at 94.83 mph.

As usual in racing, the season was ready before we were. With the engine as described, with GSM cafe racer bars and wearing Dunlop K-81 tires front and rear, the Hawk went to Ontario Motor Speedway.

And came in fourth in class. Not bad. The competition was as expected, the RDs. The good ones had more power than the Hawk. We needed power. We also needed ground clearance. A competitive surprise, this one. The Yamaha doesn’t have enough clearance to take advantage of the power and the excellent chassis, but that only hurts in Box Stock, because the Production rules allow relocation of exhaust systems. Where that can be done. The Hawk doesn’t just have two pipes. It also has an expansion chamber, of sorts, joining the two pipes and directly beneath the back of the sump. No place for the exhaust to be moved to.

So we raised the rest of the machine. No. 1 Products made some new damper rods for the Hawk forks, one set 0.75 in. longer than stock and the second set 1.25 in. longer. We put some Top Bearings, another No. 1 product, into the sliders. They give a better and longer surface for the sliders as they move on the stanchion tubes; more precise travel was needed, we thought, because the longer damper rods took away some engagement.

In back, we borrowed some shocks and springs from Works Performance. As we were to learn more strongly later, the Hawk is not thought of as a sports or racing bike, so the performance people haven’t done much development work, so would-be racers find parts hard to get, so Hawks don’t get raced, so they aren’t thought of as racing bikes . . . round and round. But we figured the Works shocks were worth a try, especially as they were an inch longer than stock and gained clearance at that end.

The second race was a downer. Willow Springs is a tight, bumpy, narrow circuit, with camber changes and dips and bumps and patches in the surface. Eagan doesn’t like the place, the rear suspension was too soft, ditto the brakes and the result was a sixth in class. Worst finish of the year.

Useful, though. We scouted around and through the good offices of MEI Services, Yakima, Wash., we got some Ferodo metallic pads for the front brakes. They worked well, lasted the rest of the season and have more power and control at the reasonable cost of $22 and some extra effort at the lever.

Eagan’s stock Hawk broke rear wheel spokes all the previous season, the rules allow wider rims and we wanted maximum tire, so the rear hub was traded for a Type I, relaced with 8-gauge spokes. A second rim, for quick tire changing, was laced with 7gauge spokes. Meryl’s Pro Wheel did the work. Both hubs got wider rims, from WM2 to WM4.

And the team got some hope. At Sears Point, nearly as twisty and bumpy as Willow but wider and faster, Pat gave as good as he got. Right up there in front, duelling with a good RD350, Eagan went so far as to have the actual lead a couple of times, albeit never at the finish line, and he took the flag in second place.

Findings: The front suspension, nearly stock, was just fine. No trouble at all. The No. 1 damper rods had stock damping, oil weight was unchanged, so the only real modification was slightly increased preload to go with the added height.

Pat mentioned that the steering felt a bit stiff at road speed, though, so the steering head bearings—which were dimpled—were replaced. As a note on the Hawk front end, the top of the stanchion tubes are held by single bolts through the top clamp. Not pinch bolts. We expected trouble here, indeed thought was given to making a replica top clamp of heavier metal. But that would have been wrong, as somebody once said, and to be caught cheating wouldn’t have been worth it. As it worked out, keeping the top bolts tight kept the tubes in line.

Braking was competitive. The later RD400s have disc rear brakes. They are better brakes, with less fade under track conditions and better control. But. The changes made from RD350 to RD400 made a more suitable road bike and a less potential Production racer. Most of the contestants for the class were RD350s and they have a drum rear brake just like the Hawk’s. Even more willing to lock, in fact, so although the last RD400 we tested had better braking than either the Hawk or the RD350, in the races 350s were the competition and the Hawk could match them on stopping power.

Power was the shortcoming vs the Yamahas. When Pat got a drive out of the turn right with the best RD, the Yamaha pulled him down the straight by 10 lengths. When Pat got a better drive, went faster through the turn and got on the power earlier, he only fell back by five lengths.

Parts again. When the Yamaha R5, immediate forebear to the RD350s and 400s, appeared, sporting little two-strokes took over the smaller classes at the road races. Couldn’t be beat, well, one guy here says page the Suzuki Twins could do it on occasion, but because the Yamahas were winners, the top teams built them and the top riders rode them and all the performance parts outfits competed with themselves in turning out more and better speed equipment. vPlus, all those teams have years of experience and watching each other for secrets.

continued on page 167

continued from page 147

Well, nobody except us said it would be easy.

Then things got tougher. At Riverside, where power rules but determination can make a challenge, Pat challenged. From ►fifth on the grid, he got into third and was closing on the leading pair.

There was this terrible noise. One of the exhaust valves dropped onto the piston crown.

Double trouble. The gearbox had been jumping out of 5th and the engine had ►been revved beyond the redline. Pat also admits, and he needn’t have, that in the heat of battle he wound it over the line to nearly 11,000 rpm.

Whatever, the engine was torn down. The valve gear was replaced and the transmission was shimmed so the engagement >.dogs would be more fully mated. The selector detent was fitted and polished. The shift lever was stiffer as a result of the shims, so a Johnson rod linkage, for more leverage, was fabricated.

Parallel to the mechanical work, we were looking for parts.

Pistons. The camshaft was as radical as the stock intake and exhaust could use. vThe head flowed all the air the engine could consume. The ignition gave all needed spark, but couldn’t be advanced.

Compression was the answer. With the “added valve lift and the shape of the Hawk’s combustion chamber, the head couldn’t be milled. Stronger, lighter ^pistons with higher crowns was the only way.

No way. The Hawk isn’t a performance engine. We tried all the major manufacturers, without success. We found a couple of custom piston makers who agreed to make a set for the Hawk to our specs.

As is well known. Things Don’t Fit.

The first set to arrive had piston crowns that didn’t match each other. Two other firms promised pistons in four weeks. After . seven weeks, we cancelled one order because work hadn't begun.

And when the third set arrived, the bottoms of the skirts wouldn’t clear the ‘'crank at BDC, while being 50 grams heavier than stock.

The engine went back together, still mostly stock, and after an all-night thrash the team hauled the 500 miles to Sears Point.

The flywheel bolt came loose. Never ^even got into contention, nor did we learn how the useful changes had worked. What happened was, the bolt holding the flywheel onto the crank was dipped in LocTite and fastened with an air wrench, good for maybe 25 lb.-ft. What we forgot was^ that the bolt needs 90 lb.-ft. No sooner was the engine revved in anger than the bolt was loosened and the flywheel walked around on the end of the crank, to the detriment of both.

Then it was 500 miles home, another rebuild, and 500 miles back to Sears Point.

Pat was off to a good start, got into the"1 lead once and was in third, close up, when the shortcomings of the rear suspension made themselves known.

The shocks were soft, we knew that, but on smooth tracks this only showed up as a sag on corners at full lean.

Sears Point is rough. Pat came through" an off-camber turn, fully compressed and the rear sank enough to ground the exhaust collector. The Hawk levered itself off the rear tire and Pat went down on the low side. No major damage, but plenty of scrapes and bruises.

Another parts problem. First, we had-' part of the cure, a set of Boge Mulholland shocks and springs. They were used, and came off one of Pat’s other bikes. Installation was a bit of cut-and-try, so while the upper mounts were being reworked, we extended the shafts half an inch, to keep the ground clearance we needed. (The. Hawk was a semi-sponsored project, by the way. The money came out of the magazine’s test budget and the pinch-penny editor never let racing fever interrupt the regular work. So we used spare parts and adapted used parts when and where we could.)

Looking back, there was a better way, Koni makes shocks to fit the Hawk, the. damping is adjustable and the springs can be swapped until the rate suits rider and track. We could have had good shocks, if we’d asked the right people, and if we' could have got the racer discount . . .

And if Springsteen didn’t have the flu, and if Bob Hannah hadn’t gone water skiing earlier in the season, and if saying if counted in racing . . .

No matter. The crash at Sears Point damaged the stock front wheel, so the stock hub was relaced, with 8-gauge spokes, onto a WM3 rim from a Honda CB750. With the wider rim we got a Goodyear slick. 3.25-19., D1949. Worked great! with excellent traction and no chatter, another sign that the tire was right for the rim and the combination wasn’t too much for the front suspension.

Best rear tire of the project was a Goodyear slick, 3.50-18, D1934. That’s the A-l compound, effective on warm tracks and not slippery when cold. We usually used 31 psi in front, 34 psi in the rear, cold.

We began the season with Dunlops,. K8 Is Mk II, 4.10-19 in front and 5.10-18 in back. They worked well, and were super on the street where the slicks are risky and illegal. It was mostly that we raced on drÿ tracks and the slicks had more traction.^ And less weight; the 3.50 slick was 9 lb. lighter than the 5.10 road tire.

continued on page 175

continued from page 168

Finally, victory. At Ontario, fast and smooth and by all rules a power track, Pa4 won the class. Just like that and it’s a shame that announcing a win isn’t nearly’ as dramatic as explaining a loss. Pat won, so we sang and danced, never mind that** the season was nearly done or that we had no hope of getting the title and still didn’t have enough power to use the rést of the^ bike or stay with the Yamahas when all was going well with them.

Boy, were we glad to have that win. See, what we were really doing was having a' good time, so although the season title was beyond us, there were still some events to come. We went to Las Vegas.

During the first few laps of practice Pat was following another bike and saw the machine twitch slightly as it leaned into a turn. -4

Next thing Pat knew, he was down, quicker than it takes to tell. A bike running earlier in practice lost a seal and dumped oil on the track. He apologized later. No hard feelings, as things like that are part of racing.

Pat walked away from the crash, slowly.^ More scrapes, more bruises, but nothing serious. The Hawk wasn’t as lucky. It lost chunks from every corner, the forks were twisted, the front wheel looked like a doughnut made in eighth-grade home ec. That’s it, the editor said, we can’t afford to prove anything else this year and I suppose we’d better get Pat a new helmet. The old one has made the supreme sacrifice. 4 Well. What did we prove?

Begin with the obvious. Racing is fun. It isn’t easy. No matter which make and model and class you pick, you’re almosl sure to have mechanical failures, to not get parts you needed and to find that lots of other people out on the track work just as hard as you do.

We proved it’s harder to campaign an underdog than it is to begin with a proven winner. \

And we proved lessons like the above aren't easy to accept.

After the second crash, we got the pistons we needed at the opening of the’ season. They came from Moriwaki, who has no outlets in the U.S. but sent a lovely pair of pressure-cast pistons anyway. 4

Pat Eagan has a good shot at a sponsored Superbike ride for 1980, which proves talent can work itself toward the top.

But, he says, with those pistons the Hawk could have the 5 bhp that kept it behind the Yamahas. 4

Just because we didn’t do it doesn’t prove it can’t be done.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue