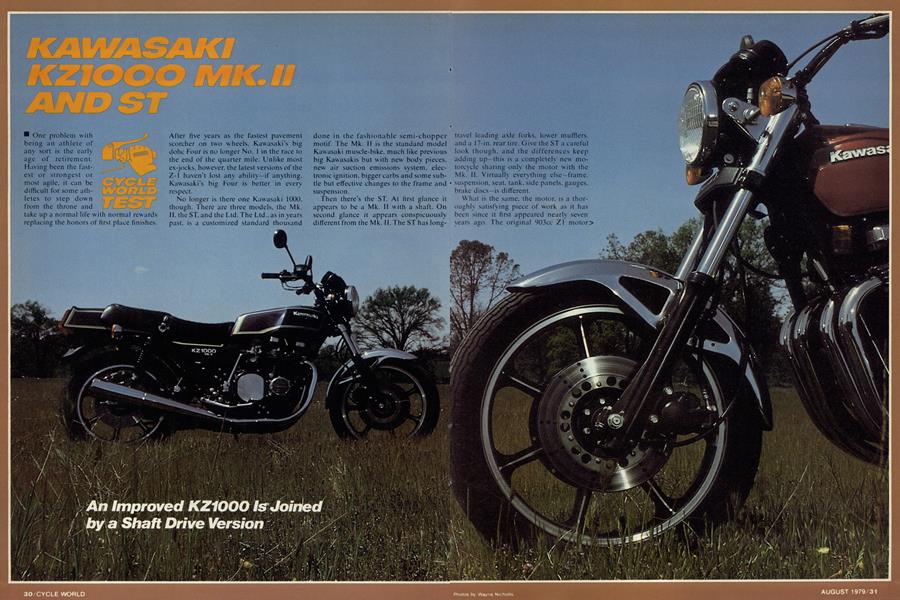

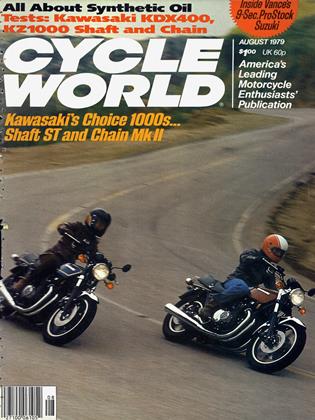

KAWASAKI KZ1000 MK.II AND ST

One problem with being an athlete of any sort is the early age of retirement.

Having been the fast-

est or strongest or

most agile, it can be

difficult for some ath-

letes to step down

from the throne and

from the throne and

take up a normal life with normal rewards

replacing the honors of first place finishes.

After five years as the fastest pavement scorcher on two wheels. Kawasaki's big dohc Four is no longer No. 1 in the race to the end of the quarter mile. Unlike most ex-jocks, however, the latest versions of the Z-l haven’t lost any ability—if anything. Kawasaki’s big Four is better in every respect.

No longer is there one Kawasaki 1000. though. There are three models, the Mk. II. the ST, and the Ltd. The Ltd., as in years past, is a customized standard thousand

done in the fashionable semi-chopper motif. The Mk. II is the standard model Kawasaki muscle-bike, much like previous big Kawasakis but with new body pieces, new air suction emissions system, electronic ignition, bigger carbs and some subtle but effective changes to the frame and suspension.

Then there’s the ST. At first glance it appears to be a Mk. II with a shaft. On second glance it appears conspicuously different from the Mk. IL The ST has longtravel leading axle forks, lower mufflers, and a 17-in. rear tire. Give the ST a careful look though, and the differences keep adding up—this is a completely new motorcycle sharing only the motor with the Mk. II. Virtually everything else—frame.

suspension, seat, tank, side panels, gauges, brake discs—is different.

What is the same, the motor, is a thoroughly satisfying piece of work as it has been since it first appeared nearly seven years ago. The original 903cc Zl motor> was both the most powerful motorcycle powerplant and the most flexible, running smoothie on regular gas. idling evenly pulling at low speed and thrilling riders at high speeds. W hen the Z1 became the KZ1000 for the 1977 model vear the bore grew from 66mm to 70mm. where it remains today, and the stroke staved at 66mm for 1015cc displacement. I hat hasn't changed.

There's still a roller bearing crank, beefed up slightly, we're told. Two earns still push the eight valves open through shim-tvpe adjusters. The 4-into-2 exhaust system introduced for 1977 has been changed, but there are still just two mufflers. An automatic spring loaded earn chain tensioner is new this year.

Last time the motor was revised, the push was on sound control. The airbox was changed to hold dow n intake roar and the earn covers were made thicker to reduce valve clatter.

This vear the push is emission control. Beginning with 1978 model street motoreveles. the Environmental Protection Agencv is requiring new bikes to meet limits on the amount of hvdroearbons and carbon monoxide coming out cd' the mufflers. The standards change each year through 1980. getting more stringent each vear. Because the standards aren't as unreasonable as automobile standards are. most four-stroke motorcycles can meet the limits with a few tuning changes like. say. leaner earb jetting and maybe a little bit retarded spark. The results of the tuning changes on many new motorcycles have been poor cold running performance and slightlv decreased power.

Kawasaki has taken a more comprehensive approach to the regulations. Not onlv are the earbs and the ignition timing changed, but there's an accelerator pump for the new 28mm earbs. the ignition system has been changed to a transistorcontrolled breakerless ignition, as Kawasaki calls it. and there is an air suction system sending fresh air into the exhaust ports to burn the carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons.

Basically, the air suction system is the same as the system used on the Kawasaki 1300 Six and the 650 Lour. Reed valves allow exhaust port suction to pull fresh air into the ports, downstream of the exhaust valves. A vacuum-operated valve cuts off the fresh air supply when there's high intake manifold vacuum, as in deceleration. to prevent backfires. Best of all. the air suction gets rid of emissions w ithout subtracting anv horsepower.

Bv adopting the TCB ignition. Kawasaki has eliminated normal points wear and adjustment, increased high rpm spark voltage and retained a long-duration spark. The TCB I is a battery and coil system using a magnetic trigger. Unlike the magnetic triggers in some CD1 units, however, the TCB pickup coils begin making the signal voltage sooner, the faster the rotor turns so the ignition coil gets enough time to build a full charge even at high rpm. There are onlv two pickup coils, cylinders one and four being paired and cylinders two and three being paired. Of course the paired cylinders mean the plugs tire twice as often as need be. but a second spark during the exhaust stroke doesn't hurt anything and simplifies the system.

This is bv far the most thorough emissions system on a motorcycle we've seen so far. True, some other motorcycles have curbs with an accelerator pump, although the vacuum controlled single pump working for all four earbs isn't that common. The inductive electronic ignition also isn't particularlv innovative, though it's not the normal CDI electronic ignition. Even the air suction system has been around on automobiles for several years. What makes the Kawasaki system impressive is the use of all these techniques together, each one working with the other.

Onlv the earb change, reverting to 28mm earbs from the 26mm earbs used since 1976. should make a significant change in horsepower. Kawasaki claims 93 bhp. 10 more than last year. Kawasaki also claims a healthy 7 ft. lb. increase in torque to 65.7 ft. lb.

Coupled with the engine changes, the final drive ratio of both the shaft and chain driven Kawasakis is lower than last year s KZ1000 which should provide better acceleration in exchange for slightly higher engine speed on the highway and a lower theoretical top speed. Transmission gear ratios remain the same for both models as in last year's bike.

At the back end of the transmission the two Kawasaki thousands become obviously different. On the Mk. II isano-ring sealed endless —630 chain. On the left end of the output shaft in the ST's transmission is a cam-type shock damper driving the front bevel gear. The damper is compressed w ith a coil spring instead of the flat washer springs used on the 1300. A priman cam-type shock damper is fitted in the clutch drive hub of the ST. The chain driven Mk. II has no shock dampers in the transmission. From the Iront bevel gears power is transmitted through a universal joint to the driveshaft in the ST's left sw ing arm and ultimately to the ring gear in the final drive housing. Unlike the driveshait operated motorcycles from Yamaha and Suzuki, the front bevel gears of the Kawasaki are entirelv within the transmission housing and run in the same engine/ transmission oil. 1 he Yamaha and Suzuki designs use a separate housing filled w ith gear"lube for the bevel gears. The relative merits mav be argued, but it is sufficient to say both methods work. The final drive does use regular gear lube.

Shaft and chain mav be the most obvious difference between the Mk. II and the ST, but in day-to-day operation all the other differences become more apparent and more noticeable.

Suspension changes are important on both models, not just the ST with the leading travel forks. The Mk. II appears to use the same suspension as last year’s KZ, but the fork dampers are modified for more compliance, there are new rear dampers and single-rate springs. Suspension travel on the Mk. II is the same as it was last year. 5.5 in. in front and 3.7 in. in back. The shaft has much longer travel, 7.9 in. in front and 4.5 in. in back. Progressive rate springs are used front and rear on the ST. 84/130 lb./in. springs on the shocks and 50/100 lb./in. in the forks. There's also a difference in physical size of the suspension components on the two bikes; the Mk. II has 36mm stanchion tubes while the ST has 40mm tubes. The rear dampers are also larger on the ST. Compared to the previous KZ1000. the ST has softer springs in back, comparable springs in the front, more travel at both ends and more weight to be controlled.

Tying together the two different suspensions are two different frames. Frame configuration on the Mk. II is the same as previous Kawasaki thousands, but wall thickness of various tubes has been changed, the steering head brace has been beefed up and the downtubes are double thickness below the steering head brace. On the ST the downtubes are single wall and connect to the steering head lower than the downtubes on the Mk. II do. While the Mk. II uses a heavy plate in front of the downtubes for bracing, the ST braces the steering head area with plates behind the downtubes. The ST also uses a cast iron plate to tie the frame tubes together at the swing arm pivot while the Mk. II uses pressed steel plates.

Frame differences between the two Kawasakis lend themselves to detail differences. The ST has a two liter larger airbox for increased intake silencing. Battery access on the ST is more convenient because the battery can be serviced by merely lifting the hinged seat; on the Mk. II the battery must be slid out from under the airbox. Larger diameter forks on the ST mean different triple clamps.

Brakes on the two bikes provide the same swept area, but there’s a difference in the discs and in the caliper mounting. Both bikes use the irregular hole pattern that Kawasaki claims reduces brake squeal. But inside the contact area of the ST’s discs are more holes, larger in diameter, apparently there to lighten the twin front discs and single rear disc. Outside diameter of the discs is different. I l.5 in. for the Mk. Il and l l.25 in. for the ST. but the single-piston calipers sweep the same size swath. On the ST the rear caliper is also moved forward of the axle and shock (it’s behind the axle on the Mk. II) which should help reduce unsprung weight slightly.

Sitting side by side, the appearance pieces of the Mk. II and ST look identical. They’re not. Both use Kawasaki’s newfound angular look with slab-sided gas tanks, squared-off tailpiece, slightly stepped seat and black painted engines-. But the gas tanks are different, the ST having a tank about l in. wider and higher to carry 4.8 gal. of unleaded gas. The Mk. Il s more compact tank holds 4.7 gal.

Both seats look the same, but the ST seat is firmer and has a more pronounced step between the rider and passenger sections. Even the handlebars are different, the ST having 2 in. narrower bars than the Mk. 11.

Despite all the changes to the machines this year, riding a new Kawasaki thousand is a familiar experience, whichever model is ridden. Sitting on either model, there are the familiar controls, including the clutch interlock for the starter. On the ST there's a gas gauge in addition to the speedometer and tach. but the self-canceling turn signals of the 1300 or Z 1-R have been left off.

Starting the engine is a simple matter of pulling up the choke, holding in the clutch and touching the starter button. The Mk. II still has a kick starter attached, but the kick starter on the ST is hidden under the batterv and requires sidecover removal to reach and some quick w renching to attach. As long as the ST is going to have a kick start lever included, we’d prefer to see it mounted on the kick starter shaft.

Haifa minute after the engine is started, the choke can be pushed off and the bike ridden away. The emissions control system really does work, allow ing the Kawasaki to run every bit as well as any pre-emission engine while meeting the ERA standards. Cold starting problems and poor cold running have been common on many of the new motorcycles, but not the Kawasakis.

Clutch pull is moderate, not as light as the Yamaha Eleven or as stiff as a Harley; throttle return spring tension is excessive, almost as stiff' as the Suzuki GS1000L. With 93 blip. 65.7 ft.lb. of torque and adequate flywheel effect, getting under way is effortless.

From low speeds on up throttle response is excellent. The accelerator pump does its job unless the motorcycle is lugging up a hill in fifth gear at. sav, 2000 rpm and the throttle is jerked wide open. Then the engine w ill bog momentarily before taking off'. Once spinning, particularly when the revs are over 5000. the Kawasakis provide thrills common to thousand cc bikes. Two years ago a 12.12 sec. quarter mile would have been outstanding, a figure only the KZ1000 could produce. Now that the motorcycling public has been exposed to the Honda CBX. Yamaha XS1100. Suzuki GS1000 and Kawasaki's own KZ1300. a 12.12 see. quarter is nothing abnormal, but it is exciting and it is powerful even if it's not the fastest thing on two wheels.

Before going to the dragstrip a variety of test riders predicted quarter mile times in the high elevens based on the power and response of the Mk. II. The shaft felt noticeable slower and turned a 12.49 sec. quarter mile. Trap speed was 109.62 mph for the chain and 107.39 for the shaft, indicating the chain driven Mk. II was putting out more horsepower. At the drags the ST was more difficult to launch, frequentie lifting the front wheel when the clutch was released too quickly or bogging. The Mk. II didn’t exhibit any problems; it just steamed away providing the rear tire didn't light up. A note about both bikes: the ST came to us w ith nearlv 8000 mi. on the odometer; the Mk. II had nearly 3000 mi. This is above average mileage for test bikes and both bikes had been well thrashed prior to our testing so the figures represent the performance of more normal motorcycles as opposed to fresh machines.

While there are faster motorcycles, the Kawasaki thousand is noteworthy for its flexibility and excellent power at all engine speeds. It pulls well from idle, isn't a bit fussy, and Kawasakis road raced and drag raced have proven the engine is durable.

What was an exceptionally smooth motorcycle engine in 1972 isn't particularly smooth by contemporary standards. An inline Four is nicely balanced for firing impulses, but does suffer from torsional vibrations. And the Kawasaki, particularly the Mk. II. lets a rider know the engine is spinning by sending a vibration through the handlebars, pegs and gas tank. Serious v ibration sets in at 5000 rpm. blurring the urethane-backed mirrors with handlebar vibration. The ST is smoother at speed but still vibrates more than a Yamaha Eleven. While the ST didn’t transmit as much vibration through the frame to the rider, several bolts on the ST vibrated loose during the test. Apparently the ST's frame is absorbing the vibration that the Mk. II transmits.

Differences between the ST and Mk. II are noticeable at the drag strip but become obvious on curvy back roads. The Mk. II is a racer’s delight. It's not small, weighing 571 lb. with a half tank of fuel, but it takes> little effort to turn at speed, doesn’t have to be wrestled through corners, is stable and secure. One test rider, also a road racer, came back from a ride and said it handled better than the Suzuki GS1000, the standard for big bike handling. Another road racer said no, it handles as well as the Suzuki, but not better. Kawasaki has finally gotten the frame right on the thousand. The shocks still would need replacement for club-level road racing, and the K87 rear tire is far too slippery for hard riding, but the motorcycle itself is right.

Starting with a fresh slate on the ST. Kawasaki didn't have as much luck making everything work together. To its credit, it only weighs 31 lb. more than the chain drive model, a minimal handicap. But it feels 60 lb. heavier when it comes to turning. And in high speed sweepers, like a particular freeway on-ramp near the CW offices, it doesn’t have the stability of the Mk. II. Again, the additional miles on the shaft may have taken a toll on the rear shocks, contributing to the difference. And there’s the ST's 17-in. rear tire, which has more sidewall area for flex. Whatever the causes, the ST is not the fine handling machine the Mk. II is, but it’s also not a poor handling motorcycle. It's competent, able to go around corners at moderate speeds; certainly a better handling and cornering motorcycle than the Honda Gold Wing, for instance.

There’s a natural tendency, not always justified, for shaft-drive bikes to be labeled touring bikes and expected to be slower and less manageable than chain driven, or sport bikes. The Kawasaki ST w ill contribute to the notion, but it also contradicts the idea that touring bikes (meaning those with a shaft) are inherently more comfortable than better handling sport bikes. The longer travel suspension of the ST allow's the motorcycle to move around more on its suspension during cornering or braking, detracting from the handling, but adding little to comfort. Compared to last year’s KZ1000. the ST has a softer and more comfortable suspension. Compared to the new Mk. II, there’s little benefit from the additional travel.

On a trip up the California coast on the two Kawasakis, both riders preferred the Mk. II for the long ride, primarily because of the better seat on the Mk. II. The ST seat is firmer and shaped so a rider slides too far forward for comfort. The shorter handlebars of the ST may be more comfortable for long distance riding, but no one noticed them until the bikes were measured. Handlebar, footpeg and control position is normal for a big Japanese bike and causes no problems. The wider gas tank on the ST, though, forced a rider’s legs to be spread apart more and made cold weather riding less comfortable.

Brakes on both Kawasakis were excellent: powerful, controllable, and requiring little effort. One rider felt the brake lever was too far from the grip but another rider preferred the position.

What with $1 a gallon gas and gas stations closing on weekends, cruising range and fuel economy are becoming more important. Ridden together on the street, both Kawasakis took exactly the same amount of fuel at stops on a trip, both getting 41.6 mpg on the CW mileage loop. On the highway the bikes would get up to 45 mpg and around town the mileage would drop to 35 mpg. At best the Kawasakis have a 200 mi. cruising range, about average. A larger fuel tank on the ST would make it a more able long distance machine, although the tank feels quite large to a rider in its present size. Both Kawasakis are quiet on the highway, but the ST with its larger airbox. lower mufflers and shaft drive is quieter when run hard. As always, the Kawasaki motor emits a whine from the primary drive gears at cruising speed. Unless a fairing is mounted the sound isn’t objectionable, just there.

Having two such similar yet different motorcycles is in some ways peculiar. Certainly Honda sells two one-liter motorcycles with the CBX and the Gold Wing, but each has a different job to do. The Mk. II and ST come across more as two different models of the same motorcycle.

As big. powerful sporting bikes go, the Mk. II is competitive with good power, -excellent handling and a long list of racepart suppliers. It’s relatively comfortable, rugged, and useful for anything a street bike should do—a fine all-around motorcycle.

Then there’s the ST. a perfectly good motorcycle that trades little bits of excel, lence for a shaft drive. Because the Mk. II works so well for so many uses, the ST doesn't need to be an all-purpose street bike, which it is. The ST will satisfy the man who wants a shaft drive motorcycle but doesn't want to sacrifice as much performance as he would have to with a Gold Wing.

What the ST isn’t, is an all-out touring bike. For that it needs more comfort and better range from a tank of gas. It has the power, reliability, silence, load carrying capacity, and good enough handling to make long distance riding enjoyable.

Kawasaki has changed the basic KZ thousand before, but never improved it as much with so few changes. When the same evolution occurs to the ST it should be outstanding.

KAWASAKI KZ1000 ST

$3599

KAWASAKI KZ1000 MK.II

$3399

View Full Issue

View Full Issue