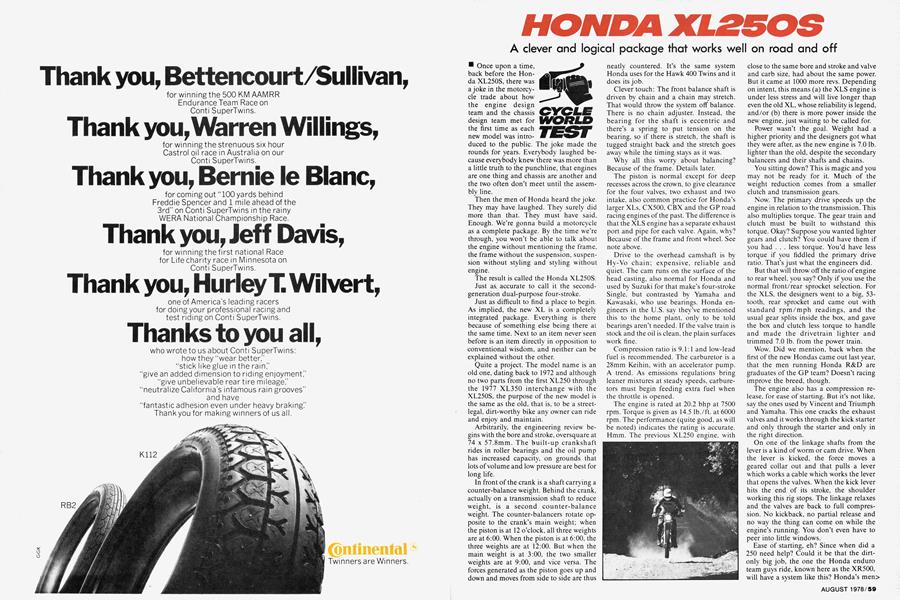

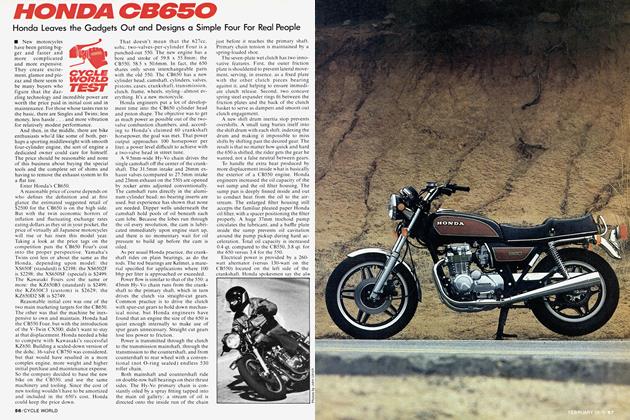

HONDA XL250S

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A clever and logical package that works well on road and off

Once upon a time, back before the Honda XL250S, there was a joke in the motorcycle trade about how the engine design team and the chassis design team met for the first time as each new model was introduced to the public. The joke made the rounds for years. Everybody laughed because everybody knew there was more than a little truth to the punchline, that engines are one thing and chassis are another and the two often don’t meet until the assembly line.

Then the men of Honda heard the joke. They may have laughed. They surely did more than that. They must have said, Enough. We’re gonna build a motorcycle as a complete package. By the time we’re through, you won’t be able to talk about the engine without mentioning the frame, the frame without the suspension, suspension without styling and styling without engine.

The result is called the Honda XL250S.

Just as. accurate to call it the secondgeneration dual-purpose four-stroke.

Just as difficult to find a place to begin. As implied, the new XL is a completely integrated package. Everything is there because of something else being there at the same time. Next to an item never seen before is an item directly in opposition to conventional wisdom, and neither can be explained without the other.

Quite a project. The model name is an old one, dating back to 1972 and although no two parts from the first XL250 through the 1977 XL350 interchange with the XL250S, the purpose of the new model is the same as the old, that is, to be a streetlegal, dirt-worthy bike any owner can ride and enjoy and maintain.

Arbitrarily, the engineering review begins with the bore and stroke, oversquare at 74 x 57.8mm. The built-up crankshaft rides in roller bearings and the oil pump has increased capacity, on grounds that lots of volume and low pressure are best for long life.

In front of the crank is a shaft carrying a counter-balance weight. Behind the crank, actually on a transmission shaft to reduce weight, is a second counter-balance weight. The counter-balancers rotate opposite to the crank’s main weight; when the piston is at 12 o’clock, all three weights are at 6:00. When the piston is at 6:00, the three weights are at 12:00. But when the main weight is at 3:00, the two smaller weights are at 9:00, and vice versa. The forces generated as the piston goes up and down and moves from side to side are thus neatly countered. It’s the same system Honda uses for the Hawk 400 Twins and it does its job.

Clever touch: The front balance shaft is driven by chain and a chain may stretch. That would throw the system off balance. There is no chain adjuster. Instead, the bearing for the shaft is eccentric and there’s a spring to put tension on the bearing, so if there is stretch, the shaft is tugged straight back and the stretch goes away while the timing stays as it was.

Why all this worry about balancing? Because of the frame. Details later.

The piston is normal except for deep recesses across the crown, to give clearance for the four valves, two exhaust and two intake, also common practice for Honda’s larger XLs, CX500, CBX and the GP road racing engines of the past. The difference is that the XLS engine has a separate exhaust port and pipe for each valve. Again, why? Because of the frame and front wheel. See note above.

Drive to the overhead camshaft is by Hy-Vo chain; expensive, reliable and quiet. The cam runs on the surface of the head casting, also normal for Honda and used by Suzuki for that make’s four-stroke Single, but contrasted by Yamaha and Kawasaki, who use bearings. Honda engineers in the U.S. say they’ve mentioned this to the home plant, only to be told bearings aren’t needed. If the valve train is stock and the oil is clean, the plain surfaces work fine.

Compression ratio is 9.1:1 and low-lead fuel is recommended. The carburetor is a 28mm Keihin, with an accelerator pump. A trend. As emissions regulations bring leaner mixtures at steady speeds, carburetors must begin feeding extra fuel when the throttle is opened.

The engine is rated at 20.2 bhp at 7500 rpm. Torque is given as 14.5 lb./ft. at 6000 rpm. The performance (quite good, as will be noted) indicates the rating is accurate. Hmm. The previous XL250 engine, with close to the same bore and stroke and valve and carb size, had about the same power. But it came at 1000 more revs. Depending on intent, this means (a) the XLS engine is under less stress and will live longer thap even the old XL, whose reliability is legend, and/or (b) there is more power inside the new engine, just waiting to be called for.

Power wasn’t the goal. Weight had a higher priority and the designers got what they were after, as the new engine is 7.0 lb. lighter than the old, despite the secondary balancers and their shafts and chains.

You sitting down? This is magic and you may not be ready for it. Much of the weight reduction comes from a smaller clutch and transmission gears.

Now. The primary drive speeds up the engine in relation to the transmission. This also multiplies torque. The gear train and clutch must be built to withstand this torque. Okay? Suppose you wanted lighter gears and clutch? You could have them if you had . . . less torque. You’d have less torque if you fiddled the primary drive ratio. That’s just what the engineers did.

But that will throw off the ratio of engine to rear wheel, you say? Only if you use the normal front/rear sprocket selection. For the XLS, the designers went to a big, 53tooth, rear sprocket and came out with standard rpm/mph readings, and the usual gear splits inside the box, and gave the box and clutch less torque to handle and made the drivetrain lighter and trimmed 7.0 lb. from the power train.

Wow. Did we mention, back when the first of the new Hondas came out last year, that the men running Honda R&D are graduates of the GP team? Doesn’t racing improve the breed, though.

The engine also has a compression release, for ease of starting. But it’s not like, say the ones used by Vincent and Triumph and Yamaha. This one cracks the exhaust valves and it works through the kick starter and only through the starter and only in the right direction.

On one of the linkage shafts from the lever is a kind of worm or cam drive. When the lever is kicked, the force moves a geared collar out and that pulls a lever which works a cable which works the lever that opens the valves. When the kick lever hits the end of its stroke, the shoulder working this rig stops. The linkage relaxes and the valves are back to full compression. No kickback, no partial release and no way the thing can come on while the engine’s running. You don’t even have to peer into little windows.

Ease of starting, eh? Since when did a 250 need help? Could it be that the dirtonly big job, the one the Honda enduro team guys ride, known here as the XR500, will have a system like this? Honda’s men> smile and say the compression release makes kicking easier so they can gear the thing to be spun more times per kick and that helps starting even for beginner«. Sure, we say. How kind of you. When can we try the XR500?

While we’re waiting, there’s plenty of time to talk about the XL250’s frame. It’s an open loop, with the engine as a stressed member, once more in principle like the Hawks, the CBX and the CX500. The New Wave at the Honda think tank believes in engines used as frame members. It’s an old idea and Honda is determined to bring it back.

There are good things about the stressed engine/frame technique. It saves weight, as three legs of a parallelogram are lighter than four. In the case of an off-road machine with tall engine and long travel suspension, not having frame tubes beneath the engine means you can have a lower top frame and lower seat for equal ground clearance. Running a down tube to the engine rather than around it means there can be more space between tube and front wheel, needed because of the suspension and wheel and we’ll get to that later, after the dual pipes and the secondary balancers.

There are things to say against the stressed engine. To the frame engineer, the engine is a nice big lump. Good for damping vibrations and bolting things to.

To the engine man, the frame is the lump. The engine produces quite enough vibrations and shakes and pulses of its own, thank you. The frame man wants stresses going in and the engine man worries about stresses going out. For the new XL, both teams must have spent a lot of time together, drinking coffee and designing an engine/frame to handle the gaff in both directions.

The frame itself has an assembled steering head, large, with a triple-tube backbone. The upper pair branches to the rear tubes and the lower back tube runs to a secondary mount, like a head steady but bigger, on the engine. The rear section is a classic double triangle, meeting the rear shocks at the back corner. The rear loop goes all the way back. (In contrast, the Suzuki DR frame has only a rear stub, with a steel fender to carry the rear of the seat and the light. We’d guess the weight of each combination is about the same. More than one way. etc.)

Here we are at the secondary balancers. Honda’s experts say the balancing act, while enjoyed by the rider, is not for people but for the frame. By cancelling the major shakes, they could use the lighter, open frame. A primary-balance Single needs the full loop to contain the forces wáthin. We’ve seen the effort it took to bring the weight down, so we can judge this antivibration/light weight project to have been a main theme.

Back to the dual exhaust pipes. Honda has been doing four-valves-per-cylinder since Moto met Guzzi. Laverda has a fourvalver. So does Yamaha. Harley did a racing four-valve. The Rickman brothers had a Triumph conversion like that. The list is as old as the motorcycle. Four valves give better ffow' and better chamber shape with less we.ight and consequently higher save revs and more power. Great stuff'.

But all these other engines used two valves joining into one exhaust port, and one exhaust pipe per cylinder. (One exception comes to mind. Rudge. And a fat lot of good it did them.)

Honda's dual pipes do allow a cooling pocket to be designed into the head, between the valves. The cool air should keep the valve seats happy, i.e. less subject to getting soft and losing seal.

That aside, if there is a pow'er gain from separate ports, how come everybody else missed it? Including the guys who did this engine and the CBX and CX500 and the four-valve Fours and Sixes from the GP wars?

One of our friends in the works says the important thing is that this application works in this frame.

Back to the frame, and that single down tube snug up against the front of the engine.

The induction experts wanted a center port, intake and exhaust. Intake was easy. Make the back tubes wide and fit carb and air box between them. The exhaust, though, if there was just one, would have to angle around the front tube, the way the older XL exhausts do. And those tubes > were farther from the engine. Falls into place, now. The two little pipes route neatly around the downtube and bend easily and quickly toward the rear. Much sharper curve, with less restriction, than one large pipe could manage. The two run to a silencer, where they become one, then the silencer joins a flattened section to clear the frame and tire and then comes a second silencer. Be interesting to see how the enduro guys deal with all this. For the street, certified at 83dB(A), the result is an inoffensive yet powerful exhaust note. Honda is so good at noise by now they can build down to silence and then add character.

The tight turn coming out of the engine is because lots of clearance is needed for the front wheel, which is 23 in. in diameter. Yokohama and Honda have been working on this for a couple years. Last year the 23in. rim and matching two-ply motocross knobby were offered as accessories. The 23-in rim and tire give a longer footprint on the ground, that is, more traction area with no more drag. And the larger diameter means a reduced angle of attack. The front wheel goes over the rut, rather than against its edge.

Further, when you raise the axle from the ground, you increase trail per steering head angle. You can have more self-centering action and more straight ahead stability with a steering head angle that turns quickly and bites on corners. The XL has a relatively short wheelbase and a steep steering head. It should snake like a trials bike but it doesn’t and the 23-in. wheel seems to be the reason.

All of which is reason enough for those funny little pipes that give the big wheel the room it needs.

Interesting front end. Notice that it has a leading axle, but that the sliders do not extend below the axle. When long travel arrived, the leading axle came with it. The sliders and damper rods and stanchion tubes can be longer, so there’s more engagement and less flex, if the axle is moved forward and out of the way.

Here, though, this isn’t taken advantage of. The XL has the leading axle’s secondary benefit. The tubes and sliders and rods and springs and all are moved back, toward the steering head. Move the mass closer to the center of rotation and you decrease momentum, meaning you reduce steering effort. The handlebars are set back behind the steering head, for steering quickness and leverage. The engineers who work on the RC and CR motocrossers also work on the dual-purpose bikes and when they decided the XL needed two-thirds of a motocross system, they provided it.

Fork internals are normal, contemporary Honda, with dual-rate springs and damper rod, no air caps. Front wheel travel checked out to 7.7 in. at the lab, the difference between our figure and Honda’s 8.0 in. being that we don’t fully compress the topping-out spring.

Rear suspension is a mix of street and motocross. The gas-charged shocks are fully 16 in. long and are set at 45°, with the rear mount being almost directly above the rear axle. A long shock body is the easiest way to get extra shock travel, because otherwise you get into struggles with linkages and leverage ratios. At 7.1 in., rear wheel travel is almost twice that of earlier XLs, is more than rival four stroke playbikes, and nearly as much as a few true enduro models. Good work.

With the tires, we return to consideration of the frame. Honest. The tread pattern for the XL-only tires was designed by Honda, working with Yokohama. It’s a funny pattern, something like a blend of trials, knobby and car-style snow tread.

It’s there because Honda’s thinkers reckoned the light and open frame would benefit from not getting vibrated by the tires. The dual intent meant something other than road treads. Honda didn’t believe the trials universal tread would be good enough for dirt work. What they wish to avoid is having the bike fitted with knobbies and ridden on the road, so they’ve gone all out to provide a truly universal tread.

There’s been work done putting the various accessories outside where possible. The air filter is behind a cover below the seat, the tool bag rides in a box hung from the rear frame hoop, the helmet lock is separate from the seat and the battery has its own house below the seat on the right, with even a window so the rider can check electrolyte level every day. Bunch quicker than burrowing beneath the seat and various panels, which is why most batteries don’t get checked until they’re dead.

Turn signals are mounted with rigid stalks on flexible rubber biscuits, another way to protect the lights without actually using Yamaha’s flexible stalks. The brake/ taillight/license plate bracket is plastic and weighs only a couple ounces. Quick way for the owner of an earlier XL to lose a pound or so. comments just such an owner.

The instrument panel has been, er, styled. Choke and ignition switch are on the instrument cluster, where they belong. There is no tachometer. Instead there is a giant odometer and trip odometer and the warning lights are set below the rim of the speedometer.

Let’s get this out of the way quickly. Whoever did the instrument panel must be the junior member of the staff. The shape, we can live with. The tach, we can get along without. The key and choke, we like. Being told in big letters that this is the counter and this the trip counter, we can tolerate. A little window to report on whether the trip odo is on or off? Shrug.

But. A rider of average height, sitting at mid seat, arms comfortably flexed, can see a row of letters:

HIGH BEAM / TURN / NEUTRAL

What the rider can’t see is the actual lights telling about the beam, signals and gearshift. The lights are hidden by the lip of the panel. Careless.

Is that the only thing we can find to complain about? Just about.

What the XL250S is, then, is the result of several light years’ work by good designers working as a team.

What they got is balance, which isn’t to say compromise.

The XLS is lighter than the previous XL250, 278 lb. with half a tank of gas, vs 312 lb. The XLS is lighter than the Kawasaki KL250, and the Yamaha XT500. (Obviously.) And it weighs a bit more, 278 to 270 lb., than the dirt-only Suzuki DR370. Suzuki’s SP370 will weigh more than the XLS, but will have a better powerto-weight ratio and thus more performance.

Speaking of that, the XLS does perform, in context. It will whip most all the 250 Singles, two-stroke or four, at the drags and in top speed. It will zip away from traffic and pull legal highway speeds with ease, albeit a passing maneuver takes more planning that it will with a CB750 or like that.

The XL250S engine is a jewel. Once the rider learns that the owner’s manual is wrong, that full choke won’t do it but full choke and squirting with the throttle at just the right time with the kick will do it, the engine will fire up at will. It will pull. Nice flywheel effect built in, plus the proverbial four-stroke torque at the low end. To kill it in tight spots, you gotta be mighty careless. Gear ratios are right, or maybe they are what they are and the flat power curve would make any ratios right. Either way, the engine is always ready when you are.

Road riding is just that. Aside from the wide bars being strange on the Interstate, there is no sense of using a dirt bike on the road. The secondary balancers may be there for sake of the frame, but they do smooth engine vibrations right off the scale. The cleated pegs feel like rubber pegs. The mirror shows what’s back there. The grips don’t numb your hands. Fantastic. All these years of saying, Well, sure it vibrates. They all do.

Now, they all don’t. The nice, thick seat is fine off road, where the rider moves about and stands up and such. On the highway, just sitting there, not so good. Padding is fine. But for a thin rider, the square shoulders are too square. And the low seat height comes in part from sloping the top, with the lowest part in front. The slope moves the rider forward, all the time.

First and perhaps the only change we’d make to an XLS would be a $25 investment in a reshaped seat. Those who want a low position, slice the padding level. If more height is ok, build up the front.

Highway ride is a bit bouncy, as the short wheelbase and suspension set for the dirt give something of a chop on pavement.

Brakes look small on the spec chart and they are small. Not too small. The little drums allow a firm grip (or stomp) on pavement and they will bring the bike to a halt within a reasonable distance. Odds are they’ll fade under a series of all out stops, but then, the XL rider likely won’t engage in cafe warfare anyway. The high effort/ low skid ratio is fine for dirt.

Dirt. Unusual reactions in re off road riding. The consensus is that the XLS handles as well as any 278-lb. production dual-purpose bike can handle, that is, pretty damned well.

From there, divergence. The fast men, the enduro and point-to-point racers say the XL is perfect for its intended use. Corners on rails, doesn’t kick sideways, and provided tire pressure is dropped to 12 psi front, 15 rear, the XL tracks in the sand, soaks up rocks, ’doesn’t bottom on crossgrain. Neat.

One of our cowtrailers agreed, another claimed that at low speed across ruts and jumps, there wasn’t enough damping. The shock dyno shows that it isn’t a lack of damping. Rather, the springs are stiff. At low speeds they can overcome the rebound control. As speeds and loads increase, the spring rate becomes right and the damping is fine. The rear suspension is thus tuned to be just a bit better than the beginning rider. Can’t fault that.

The tires, breakthrough or not, are hard to rate. No question they are better than the standard trials tread on pavement and on dirt. They make less noise and have more grip, wet or dry. They even ignore the dreaded rain grooves on the highway.

As to Honda’s tread vs knobbies, until we develop the definitive off road tire testcheck the road tire comparison test elsewhere in this issue—we won’t be sure whether the Honda design is as good as it seems to be.

The XL went through mud, and sand, and over rocks. But because the entire bike is new. we weren’t able to separate the tires from the engine from the suspension.

The 23 in. front wheel rates three out of four. The flaw is that for an expert, the tire turns too well. Where the fast man expects to slide a tight turn at speed, he is forced to make a sharp turn. The long contact patch makes the steering heavy and slows him down.

Slower riders, those of us who have trouble making the bike go where it’s pointed, will not consider this a flaw.

Finally, appearance. The XL250S looks like How Honda Does It. Like the Hawks and CBX and CX500, the XL250 strikes the eye as strange, at first. Also like the other new-generation Hondas, the XL has a different look for good reason. The 23-in. wheel and the need for ground clearance and wheel clearance and low seat height have produced a definite slope from steering head to seat. Rude persons here say the XL looks like it was sat on too hard by a fat man.

Maybe so. At first. After the first 1000 miles, though, after the XL has tackled and conquered any terrain you can find, and gone to the store and to work, in comfort, at 60 mpg, well, there is an engineering cliche that what looks right, is right.

In the XL’s case, what is right soon gets to look right.

HONDA

XL250S

SPECIFICATIONS

$1249

PERFORMANCE

FRONT FORKS

REAR SHOCKS

Tests performed at Number 1 Products