WORKS PERFORMANCE SHOCKS

EVALUATIONS

Adjustable, Rebuildable and Effective

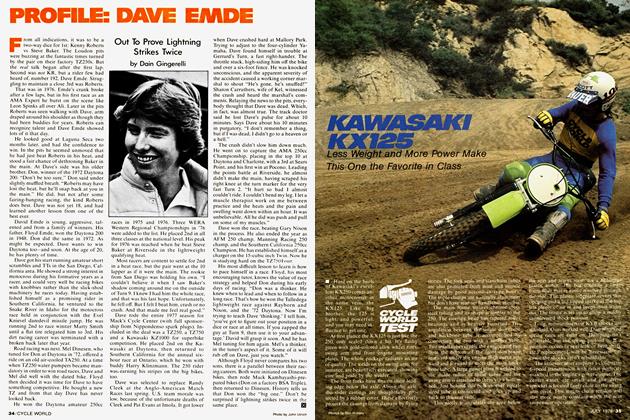

Dirt bike suspensions have taken giant leaps up the evolutionary scale the past few years. Forks with almost a foot of travel are standard on the new Honda CR250R. Incredible. But impressive as some of the new forks are, the real progress has been at the rear of the motorcycle, not only in increased wheel travel, but also in the quality of that travel.

When forward-mounted, then cantile vered and lay-down shock positions first became popular, it was impossible to find a pair of shocks that didn't heat up and lose most of their damping after 15 minutes of fast, hard riding. These positions created greater loads and caused the shocks to work much harder. These positions offered such superior wheel travel and handling that serious riders modified their machines for long travel anyway. Even with their shocks red hot, an advantage in handling was gained.

Many people started working on the problem. The most Obvious solution seemed to be the use of external cooling fins to dissipate the heat. These helped some but usually not enough.

The problem seemed tobe aggravated by the air space inside the shock itself. Pressurizing the shock seemed a logical way to stabilize the shock's action. This was accomplished in several ways:

DR. DE CARBON:

This type of shock uses a chamber that is pressurized and separated from the oil by a floating piston that moves to compensate for load, heat, etc.

OIL EMULSION:

With this approach the oil and nitrogen are combined and the whole body is pres surized.

FREON BAG:

This type requires a shock with a car tridge damping system. The sealed bag of nitrogen is wrapped around the cartridge and stays between the shock body and cartridge.

All of these types were and are effective, but the pros still had some trouble with heat and fade.

The next solution was shock bodies that held more oil. Then reservoirs were added to further increase total oil volume.

About the time almost everyone was convinced that they had to have some type of gas-charged shock to be competitive, a guy named Gil Vail!añcourt started mak ing custom shocks without gas pressuriza tion. They had chrome-moly steel bodies with large aluminum cooling fins molded to them, and a novel progressive damping system. Gil's shocks used spring-loaded check balls to control spike (sudden) loads and an unsprung ball check valve for compression damping. Rebound damping was a simple hole, without check valve.

continued on page 84

continued from page 82

This system can be tuned to work well on a wide variety of terrain.

The parts were contained within a machined aluminum piston sealed by a teflon ring. Stainless steel shafts, of Vi-in. diameter, shot-peened chrome silicon springs and bodies protected with rust-proof coating completed Gil's Works Performance product. The shocks were (and are) rebuildable and it didn’t take long for a few fast riders to discover the brand. They knew a non-charged shock could work in a cantilevered position, but many other people refused to believe it.

So Gil began experimenting with nitrogen-charged units. After extensive testing Gil developed a gas-charged shock that he thought was superior to his non-gas unit. It is an oil-emulsion type and works well.

Gil is a very fast desert rider and tests all of his modifications and newdesigns. He takes several sets of shocks with different modifications and heads for the desert. If a modification or new design is acceptable, a 1500-mile desert torture test is conducted. This sometimes takes a week of being camped in the Mojave. If any failure occurs the design goes back to the drawing board. After the redesign another 1500mile test is run. After torture testing, a few pairs then go to pro motocrossers and desert experts for their opinions. His own 250 and 400 KTMs are always in a state of development. He is constantly making modifications and testing new' ideas. Some work, some don’t.

Gil’s latest creation is a reservoir shock. “Certainly not the most original idea,’’ you say. Look closer.

His reservoirs have large fins, can be mounted to his existing gas bodies (with some internal valving changes) or can be remotely mounted.

Probably the best thing about his reservoir shock is the way the pressurization works. He thought all the present approaches could be improved upon. His design uses a rubber bladder to separate the oil and nitrogen. This bladder is located in the reservoir. By using a bladder, he could made the shock more responsive to small variations in ground surfaces. The system doesn’t produce heat the way a shock with piston separator does. In a DeCarbon shock, for example, after a bump is hit, the internal shock pressure has to be quite high before the floating piston with its O-ring seals can overcome the seal drag and move. On larger bumps they work well, but not on the smaller ones.

With the Works design the bladder can react to the smallest pothole without first overcoming the drag and stickiness associated with the separating piston types. This means the rear wheel is able to follow irregular ground much better. When the wheel follows the surface the motorcycle can accelerate and stop faster. By following and not skipping across the bumps, rider fatigue is reduced and more control of the machine is possible.

Gil has also recently started using compounded dual-rate springs. Typical of Gil’s never-ending development, he has taken the design a step farther and the owner can fine tune the spring.

The idea is simple. Compounded springs consist of two springs: a long one and a shorter, stiffer one. The purpose of the short spring is merely to act as a movable stop for the longer spring to push against. When the short spring stops moving you are left with a straight spring rate. By varying the amount of travel available to the short spring you can select the exact amount of wheel travel desired before the change of spring rate occurs. Thus, by simply changing the length of the short spring’s travel limiter, the stiffness of ride can be altered.

Gil’s latest shocks also have a cone-type bottoming bumper. This bumper has the ability to collapse to almost nothing, thus gaining more actual travel. We have used Works shocks on several of our long-range project bikes. We just installed a set of the reservoir units on our latest test bed, a Maico 450 Magnum wre are setting up to race in Baja.

W'e haven't experienced even one failure on Gil's shocks. The springs don't break, sag, or rub on the bodies. Even the shock eye bushings seem to last forever.

W'orks Performance shocks are custom built. For stock suspension application he needs to know: year, brand, model, rider weight, type of riding (MX, enduro, etc), level of ability (Novice. Amateur, Pro).

For modified frame applications: distance from swing arm pivot to top and bottom shock eyes, swing arm length, shock length (eye-to-eye), length of stroke desired, rider weight, type of riding, level of ability.

Works shocks are priced as follows:

The original $114.50 The Gasser $139.95 The Remote $199.95 Reservoirs only—$60/pair plus $15 installation.

All Works shocks come complete with springs.

Contact: W'orks Performance 20970 Knapp St.

Chatsworth. Calif. 91311 (213) 998-1977 El

View Full Issue

View Full Issue