LOAD LEVELING SYSTEM FOR MOTORCYCLES

Many motorcycle riders face a problem, unique to that mode of transportation. Even the largest motorcycle is severely affected by changes in gross vehicle weight which would barely be noticed on the typical automobile. For example, adding a 150-1b. passenger to a 3000-1b. car (with 150-1b. driver) results in less than a 5% increase in the vehicle’s gross weight. Substitute a Honda Gold Wing for the auto, and GVW (gross vehicle weight) increases by nearly 20%. Add another 100 1b. or so in the form of saddlebags, scoot boot, and contents, and the GVW has risen more than 30%, nearly ⍑ over the solo weight.

The problem is compounded because almost all the additional weight has been placed directly over the rear wheel. Allowing for the rider’s weight distribution, this typical touring payload has increased the load on the Wing’s rear end by over 55%. Imagine stuffing a pair of GL 1000s and riders in the trunk of the 3000-lb. car— that’s a close approximation of the burden placed on the bike’s rear suspension by our touring package. Obviously, it would take more than a headlight adjustment to compensate.

Several methods are currently employed to cope with increased payloads. The easiest is stiffer springs. This method does have its disadvantage. Higher spring rates are fine for supporting increased payloads, but remove the added baggage and you have a problem on the opposite end of the scale. The suspension becomes much too stiff for comfort. This semi-permanent solution is an either-or proposition: Either it’s too soft, laden, or too firm, unladen.

Another solution entails the use of air under pressure as the spring medium. For motorcycles, a derivative of the automotive air shock is used to replace, rather than supplement, the original units. Compressed air, typically at 40 psi and up, is the only spring medium. To compensate for varying payloads, one simply adjusts the pressure. A small hand pump will usually do the trick, but more elaborate systems incorporate an electric air compressor, located in fairing or saddlebag.

This is a good way to compensate for load variances, but it too has limitations. For one, the air bladder, which is larger in diameter than a coil spring, requires additional clearance. Limited space, especially near the chain guard, may not allow such an installation on some machines.

Another aspect of air springing is considered advantageous by some, and the opposite by others. The spring rate of the air bladders increases as the shocks are compressed, and rises progressively throughout the entire range of travel. Coil spring rates on the other hand, are usually linear. Proponents of air springing say its high progressivity is good, as it prevents the suspension from bottoming under heavy loads. Opponents say it’s not so good, for almost the same reason. The limited quantity of captured air makes the spring rate rise too high, too fast, they say. Choosing an air pressure which works well during the first inch or so of stroke may make the effective spring rate too stiff for the remainder of travel.

Another consideration is that when the shock is compressed, the temperature of the air molecules rises, which in turn causes a further increase in pressure. The more sudden the jolt to the rear suspension, the more pronounced the effect as the internal air temperature tends to rise higher with an increase in velocity. In other words, the harsher the bump, the stiffer the suspension. Each side does concede, however, that air shocks are operational over an extremely broad range of load applications.

Lastly, some are dissuaded by the thought of a burst bladder or broken pressure line, either of which would allow the rear suspension to settle into the fullycompressed position. Improper installation or foreign object damage would prob-> ably be the cause, as the bladders themselves are extremely durable.

LEVELER CYLINDER

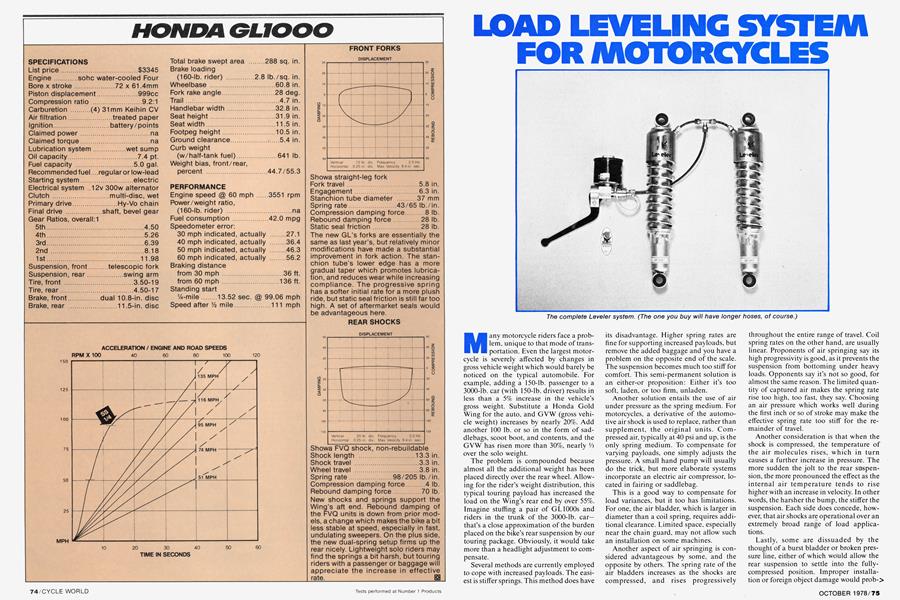

SPRING CURVES

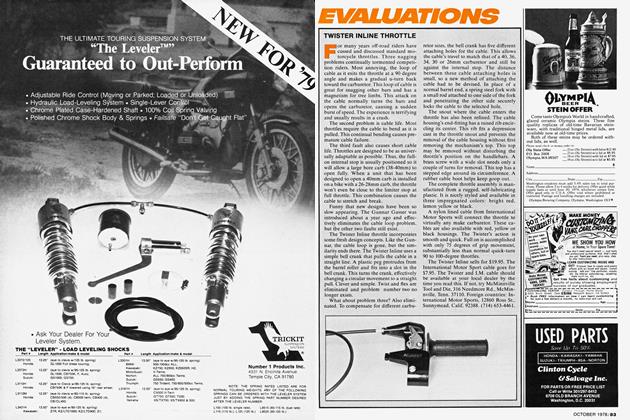

Enter the Leveler, by Number 1 Products, a different approach toward solving the variable-load problem. While it is undoubtedly the most mechanically complex of any of the adjustable systems, it is perhaps the easiest to operate—adjustments can be made while underway—and is truly fail-safe. A broken line or other lost-pressure failure does not allow the suspension to collapse. Rather, the suspension reverts to non-Leveler, conventional operation. In principle, the Leveler’s operation is quite simple, one of those “Why didn’t someone come up with it sooner?” innovations. Instead of using air as the spring medium, the conventional coil spring is retained. To compensate for varying weight conditions, a hydraulic cylinder loads the coil spring in much the same manner as a cam-type preload adjuster. But because of the additional stroke of the Leveler’s cylinder, this system can affect changes in the coil spring’s dynamics impossible with a preload adjustment alone.

The Leveler system has two main parts; the piston/cylinder, which goes atop a # 1 GP-series shock, and the pump. The piston fits inside the shock’s spring cover and is actually a nylon ring, between the cover and the shock body. Because the cylinder can be mounted on the standard # 1 shock, and the shock replaces original equipment shocks for most makes and models, the Leveler can be used on most street bikes.

Pump action is clever; stroke the lever through 90 percent of its travel and pressure goes from the master cylinder to the activated cylinders. To release, pull the lever all the way in. A series of check valves opens and the fluid goes back into the reservoir. Because the lever controls everything, pressure can be adjusted under way.

The reservoir’s transparent wall has graduated markings, 0 through 6, and shows the amount of fluid pumped into the shock cylinders. After the rider is familiar with the system’s operation, he can adjust the system for known loads according to the reservoir level. To aid in checking the level, a thin, white plastic disc, floating on the fluid’s surface, is easily visible. When the fluid level approaches the bottom of the reservoir, the disc acts as a check valve, and prevents air from being pumped into the system.

Installing the' Leveler system is quite simple, as we found when we made the swap on our long-term Kawasaki KZ1000. The shocks are bolt-on replacements for the stock units, and the pump/reservoir is held in place by a stainless-steel hose clamp. The reservoir was originally a handlebar-mount unit. It can also be mounted to the behind-the-seat grab bar, or to a luggage rack. Once the shocks and pump are in place, it is a simple matter to cut and fit the nylon tubing and Tee-connector. The reservoir is then filled with type “A” automatic transmission fluid, and the pump is stroked to fill and bleed the system. A lack of bubbles in the transparent reservoir line shows that all air has been purged from the system, which can then be topped off and capped. The installation will normally require an hour or so, and needs no special tools or talents.

Stroking the pump lever does indeed have a marked effect on rear suspension. Seat-of-the-pants readings correlate the indication of the reservoir’s fluid level, and a visual indication is evident by watching the springs compress with each stroke at the pump. Out on the road, a definite effect can be felt as the system is adjusted and is most evident when a large change in GVW is made—the addition of a passenger, for example. A little bit of stroking will compensate for the extra weight, and provides a firmer, more controlled ride.

In addition to the Leveler’s weight-compensating ability, it can also be used to tune the rear suspension for varying road conditions. The rider can choose between a soft spring setting, and a soft ride, or boost the spring rate for a firmer, solid ride with more road feedback.

continued on page 85

continued from page 76

When traversing level stretches with periodic bumps, such as the seams on freeways, the Leveler can, to a certain degree, change the overall suspension feel of the bike. Because of the interaction between front and rear suspension, a hobby-horse type of motion is sometimes induced on such stretches. By adjusting the effective rear-spring rate, and hence its resonant frequency, such rocking motions can be tuned out, and changed to simple up-anddown suspension movement.

In a manner of speaking, the Leveler is nothing more than a sophisticated preload adjuster. But the key to its operation is the amount of preload possible, and the effect this increased preload has on spring rate. The accompanying spring curve chart represents the rates of the spring, a 95/125 unit, mounted on a Leveler-equipped shock.

At the softest setting—fluid level: 0— there is about 75 lb. of static preload. For the first 1.4 in. of shock travel, corresponding to 1.9 in. at the rear wheel, the spring rate is 95 lb./in. The remainder of the wheel travel is at the higher, 125 lb./in. rate. This setting is comparable to the # 1 Products conventional shock/spring components, and feels similar to the stock KZ units.

At the next setting shown—fluid level: 2—preload is increased to 130 lb. But in addition, the transition to the 125 lb./in. rate occurs sooner. After approximately 1.0-in. shock travel—1.4-in. wheel travel— the higher rate comes in.

At the next two positions, the secondary spring rate occurs even sooner. At maximum-fluid level: 6—the higher rate comes in after less than 1 in. of wheel travel. The remaining 3-in. wheel travel is at the 125 lb./in. rate.

By adjusting the Leveler, one determines the point at which this second,> higher rate comes into play. But because we are dealing with a dynamic system, the net effect of such changes will be felt as the average spring rate, which is pressure divided by travel.

continued from page 85

This range of effective rates is sufficiently broad to handle most riding needs with ease. But for full-up touring treks, the suspension may be stiffened even more by using the cam-type preloads which are still operational on the Leveler shocks. By setting the mechanical preload higher, the spring curves are all shifted upward, raising the average spring rates.

Which brings us back to one of the original questions, that of the need for the Leveler over the original cam preload adjuster. Primarily, there’s just no way a mechanical adjuster can provide enough travel to offer average spring rates which span a range broad enough to cover the differences in GVW. But if you’re subject to the loads imposed by a weekend jaunt, a friend on the back, or both, the Leveler just might be the accessory you’ve been waiting for.

Two notes of caution: The weight limit of most motorcycles is set by the tires. With a stock bike, you can see when the load is getting close to the limit because the rear suspension is down on the stops. With the Leveler, though, the back can be pumped up again . . . but the tires still may have more weight than they can bear. Keep it in mind when you’re planning a long trip.

In the same vein, all that weight on the rear axle will have an effect on the machine’s handling. Total weight is up and weight distribution has been changed. Just because the bike is riding level doesn’t mean it won’t handle differently.

Sugg. Retail: $149.95 Number 1 Products, Inc. 4931 North Encinita Ave. Temple City, Calif. 91780

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontYou Can't Take the Harley Out of the Boy

October 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

DepartmentsBook News

October 1978 By A.G., Chuck Johnston, Michael M. Griffin -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1978 -

Short Strokes

October 1978 By Tim Barela -

Technical

TechnicalYamaha It250/400 Steering Fix

October 1978 By Len Vucci