DESAMODROMOLOGY

It sounds a bit like Jabberwocky, but desmodromic valve actuation is post-Lewis Carroll and a good deal less mysterious—once you understand it.

Desmodromy means positive valve control; one cam follower pushes the valve open, another one pulls it shut. Which means no valve springs. Which means no valve float, no broken valve springs and, theoretically, higher performance potential.

Although Ducati is the only firm to run desmodromic valve systems on production bikes, the concept antedates the advent of these machines by over 30 years. The first positive valve control system was patented by an Englishman, F. H. Arnott, in 1910 and was later adapted to the French Delage Grand Prix cars for the 1914 season.

Delage had only limited success with the system, as did several other auto firms experimenting with positive valve control during the Twenties and Thirties—Arnott, Peugeot, Brewster and Ballot notable among them. But in 1954, Mercedes installed desmodromic valve control on its W196 Grand Prix machines, and later its 300SLR sports/racers. This time the success was hardly limited. During the 1954 and ’55 seasons the Mercedes cars were virtually unbeatable, totally dominating GP and endurance racing until the firm withdrew from competition following Pierre Levegh’s tragic crash at Le Mans in 1955.

The success of the Mercedes desmos hardly went unnoticed, of course, and one enthusiastic observer was Dr. Fabio Taglioni, who had joined Ducati Meccanica in 1954. The Bologna firm was just getting started in motorcycle production, but the combination of Mercedes successes and Dr. Taglioni’s enthusiasm (he’d been sketching up desmo systems for motorcycle application since 1948) led Ducati to set its sights on Grand Prix racing. It looked like a good chance for a small company to attract attention to itself.

And so it proved to be. “Dr. T.”, as he is known to Ducati faithful, had his first desmo engine, a 125cc Single, running in 1955 and the race bike was ready to go for the 1956 Swedish Grand Prix.

That race really put Ducati on the map, because with Degli Antoni up the newcomer won its first time out, beating the previously unbeatable MV Augusta team in the process.

Despite its encouraging start, and a class win in the Barcelona 24-Hour Grand Prix d’Endurance later the same year, Ducati wasn’t prepared to mount an all-out Grand Prix effort until 1958. This wound up being something of a disappointment to Dr. T, inasmuch as the 125cc title went to MV Augusta and Carol Ubbiali once again, but it was the making of the Ducati legend. Ducatis won the Belgian, Swedish and Monza Grands Prix, taking the first five places at the latter.

The following season was the end of factory Grand Prix racing for Ducati, although some excellent one-off machines followed, such as the 250cc desmo Twin campaigned very successfully in Britain by Mike Hailwood that same year. Other companies looked at the possibility of adapting the desmo design to their own bikes—Norton’s Bert Hopwood came up with an interesting desmo variation for the company’s famous Manx Single —but none of them ever made a commitment to the system.

Ducati was even more alone when it introduced desmo versions of its street bikes in 1968. And so it remains today.

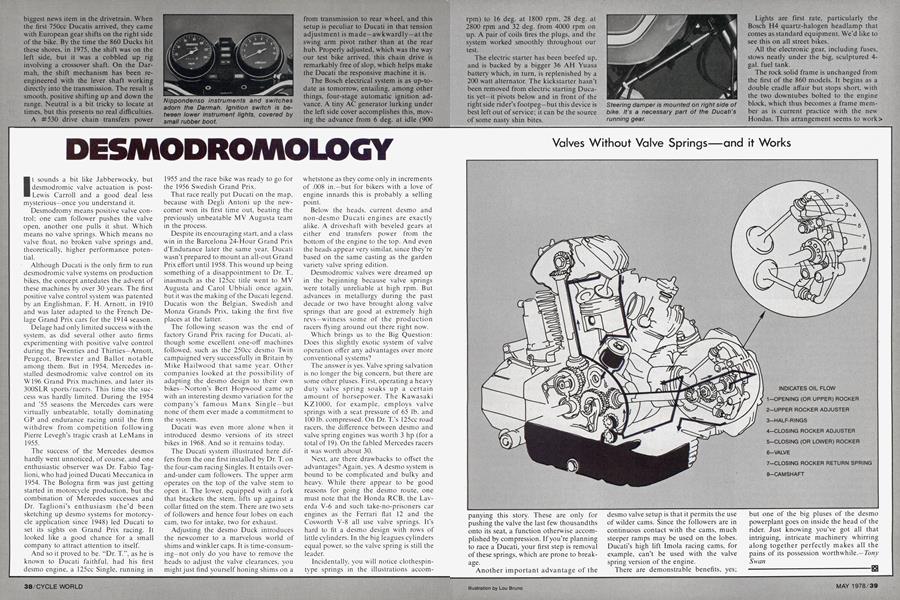

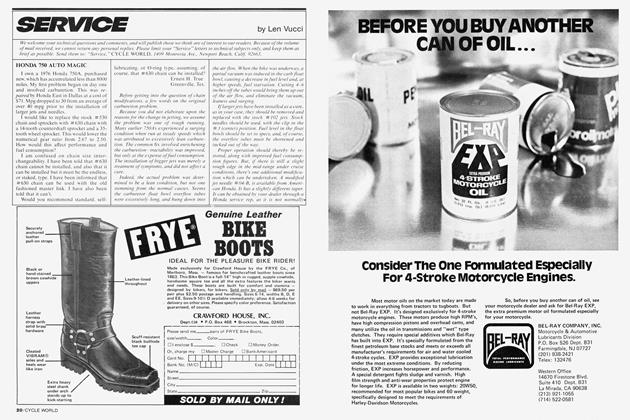

The Ducati system illustrated here differs from the one first installed by Dr. T. on the four-cam racing Singles. It entails overand-under cam followers. The upper arm operates on the top of the valve stem to open it. The lower, equipped with a fork that brackets the stem, lifts up against a collar fitted on the stem. There are two sets of followers and hence four lobes on each cam, two for intake, two for exhaust.

Adjusting the desmo Duck introduces the newcomer to a marvelous world of shims and winkler caps. It is time-consuming—not only do you have to remove the heads to adjust the valve clearances, you might just find yourself honing shims on a whetstone as they come only in increments of .008 in.—but for bikers with a love of engine innards this is probably a selling point.

Below the heads, current desmo and non-desmo Ducati engines are exactly alike. A driveshaft with beveled gears at either end transfers power from the bottom of the engine to the top. And even the heads appear very similar, since they’re based on the same casting as the garden variety valve spring edition.

Desmodromic valves were dreamed up in the beginning because valve springs were totally unreliable at high rpm. But advances in metallurgy during the past decade or two have brought along valve springs that are good at extremely high revs—witness some of the production racers flying around out there right now.

Which brings us to the Big Question: Does this slightly exotic system of valve operation offer any advantages over more conventional systems?

The answer is yes. Valve spring salvation is no longer the big concern, but there are some other pluses. First, operating a heavy duty valve spring soaks up a certain amount of horsepower. The Kawasaki KZ1000, for example, employs valve springs with a seat pressure of 65 lb. and 100 lb. compressed. On Dr. T.’s 125cc road racers, the difference between desmo and valve spring engines was worth 3 hp (for a total of 19). On the fabled Mercedes racers it was worth about 30.

Next, are there drawbacks to offset the advantages? Again, yes. A desmo system is bound to be complicated and bulky and heavy. While there appear to be good reasons for going the desmo route, one must note that the Honda RCB. the Laverda V-6 and such take-no-prisoners car engines as the Ferrari flat 12 and the Cosworth V-8 all use valve springs. It’s hard to fit a desmo design with rows of little cylinders. In the big leagues cylinders equal power, so the valve spring is still the leader.

Incidentally, you will notice clothespintype springs in the illustrations accompanying this story. These are only for pushing the valve the last few thousandths onto its seat, a function otherwise accomplished by compression. If you’re planning to race a Ducati, your first step is removal of these springs, which are prone to breakage.

Valves Without Valve Springsߞand it Works

Another important advantage of the desmo valve setup is that it permits the use of wilder cams. Since the followers are in continuous contact with the cams, much steeper ramps may be used on the lobes. Ducati’s high lift Imola racing cams, for example, can’t be used with the valve spring version of the engine.

There are demonstrable benefits, yes; but one of the big pluses of the desmo powerplant goes on inside the head of the rider. Just knowing you’ve got all that intriguing, intricate machinery whirring along together perfectly makes all the pains of its possession worthwhile.—

Tony

Swan