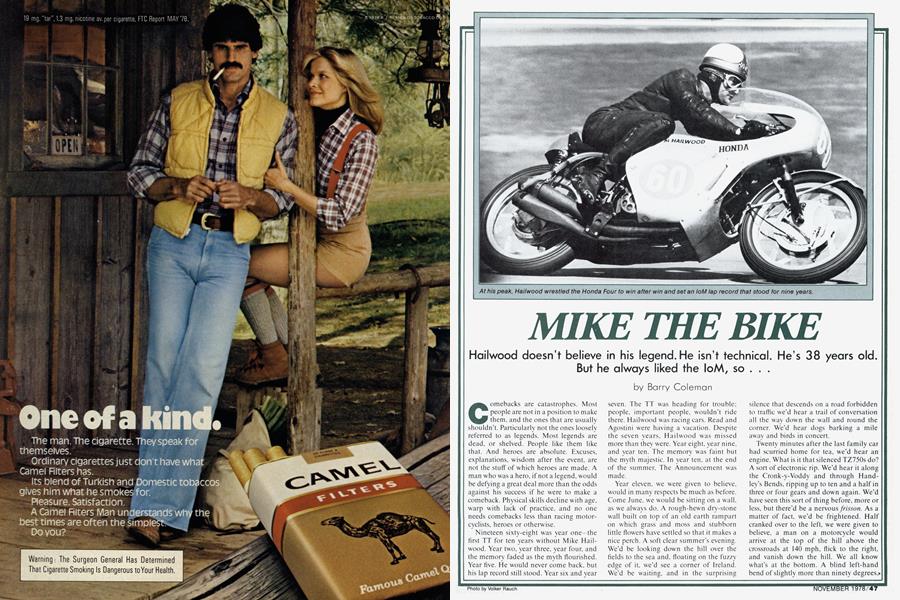

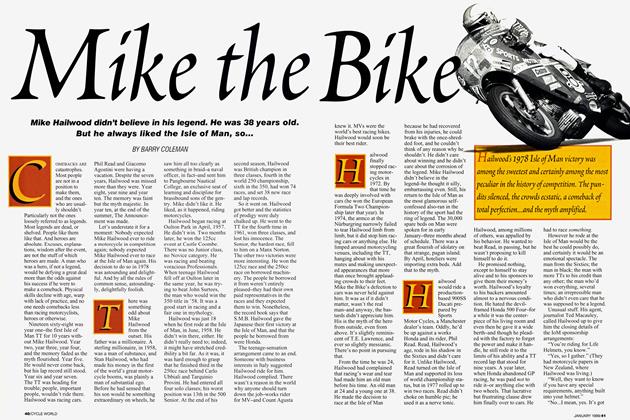

MIKE THE BIKE

Hailwood doesn't believe in his legend. He isn't technical. He's 38 years old. But he always liked the loM, so . .

Barry Coleman

Comebacks are catastrophes. Most people are not in a position to make them, and the ones that are usually shouldn't. Particularly not the ones loosely referred to as legends. Most legends are dead, or shelved. People like them like that. And heroes are absolute. Excuses, explanations, wisdom after the event, are not the stuff of which heroes are made. A man who was a hero, if not a legend, would be defying a great deal more than the odds against his success if he were to make a comeback. Physical skills decline with age, warp with lack of practice, and no one needs comebacks less than racing motorcyclists, heroes or otherwise.

Nineteen sixty-eight was year one-the first TT for ten years without Mike Hail wood. Year two, year three, year four, and the memory faded as the myth flourished. Year five. He would never come back, but his lap record still stood. Year six and year seven. The TT was heading for trouble: people. important people, wouldn't ride there. Hailwood was racing cars. Read and Agostini were having a vacation. Despite the seven years. Hailwood was missed more than they were. Year eight. year nine, and year ten. The memory was faint but the myth majestic. In year ten, at the end of the summer, The Announcement was made.

Year eleven, we were given to believe, would in many respects be much as before. Come June, we would be sitting on a wall, as we always do. A rough-hewn dry-stone wall built on top of an old earth rampart on which grass and moss and stubborn little flowers have settled so that it makes a nice perch. A soft clear summer's evening. We'd be looking down the hill over the fields to the sea and, floating on the fuzzy edge of it, we'd see a corner of Ireland. We'd be waiting, and in the surprising silence that descends on a road forbidden to traffic we'd hear a trail of conversation all the way down the wall and round the corner. We'd hear dogs barking a mile away and birds in concert.

Twenty minutes after the last family car had scurried home for tea, we'd hear an engine. What is it that silenced TZ75Os do? A sort of electronic rip. We'd hear it along the Cronk-y-Voddy and through Hand ley's Bends, ripping up to ten and a half in three or four gears and down again. We'd have seen this sort of thing before, more or less, but there'd be a nervous frisson. As a matter of fact, we'd be frightened. Half cranked over to the left, we were given to believe, a man on a motorcycle would arrive at the top of the hill above the crossroads at 140 mph, flick to the right, and vanish down the hill. We all know what's at the bottom. A blind left-hand bend of slightly more than ninety degrees, with the corner of a house for its apex. If he got it right, the motorcyclist would hit the bottom, lose every inch of suspension travel, shoot across the apex within inches of the wall at 150 mph and proceed on his way. That's if he got it right. This one would. This particular motorcyclist. The Announcement said, would be Mike Hailwood. Let's understate it for a moment; nobody expected Mike Hailwood ever to ride a motorcycle in competition again; nobody expected Mike Hailwood ever to race in the Isle of Man again. His decision to do so was astounding, and delightful. And by all the rules of common sense, astoundingly, delightfully foolish.

There's no parallel for it. It's not even a question of a comeback. In 1967 Hailwood rode his last ' race in the Isle of Man. against, among others, Giacomo Agostini. Ago on the MV, Mike on the works Honda Four—something that handled like a loosely connected pair of garden gates with. as it happens, the throttle tied on w ith a handkerchief. After a race of swapping seconds, even milliseconds on corrected time (TTs are run on time and Mike and Ago met only briefly in the pits), the MV's chain broke and Hailw'ood, having set a new lap record, won.

Tw'o years of fond memories can put a gloss on a remarkable career. Five can make a hero. Eleven can take an outstanding figure a long w'ay towards demi-deity. Hailwood isn't just remembered as a great rider, many times a w'orld champion. Hailwood, as no other rider in British or perhaps world racing, is believed in.

When Mike Hailwood, a young man of 37, ambled grinning politely out of the misty dream of his ow n legend, the universal moment of disbelief (everyone thought that whoever told them, including radio. TV. and newspapers, was kidding) was

followed by the universal asking why. The believers said the legend w'ould be tarnished. shattered even (supposing he didn't w in?), and wondered why he'd do it; bystanders asked why a wealthy and intelligent man who had survived not only riding a motorcycle faster than anyone else in the w'orld for several years but also a career in Formula One car racing would stick his neck out yet again. Everyone wondered.

Hailwood was a yardstick. Three years ago when Mick Grant lapped the TT course in excess of 110 mph there was admiration; people were impressed. But TT enthusiasts have polished memories. The men and women who have been spectators since the TT began are now very old; even those who witnessed the titanic struggles of the Güeras, Nortons, and MVs of the fifties or the quiet arrival of the Japanese in the sixties have left their youth, though not their dedication, behind them. On cool days they wear dark w'axed-cotton oversuits as they watch the racing and when the sun comes out they strip to their informais as they always did in the eternal summer when Duke, Graham, McIntyre, and Agostini rode around the Gooseneck, and they remember all that only too well. "Ah yes," they said of Grant and his Kawasaki HR750, and of John Williams and his RG500 Suzuki a year later when he rode round at 112 mph. "Marvellous." And they meant it. Then, in the same breath: "But what would Hailwood have done on bikes like those?" They always ask that, because among the things they remember is the fact that Hailwood, in 1967, rode around the Isle of Man at 108.67 mph on a 500cc Honda Four that handled so badly that to see it coming towards one was to suspect oneself of having developed a sudden acute case of astigmatism: double or treble vision.

They all saw' it go past, down Barregarrow ("Begaro"), past the house that stands in for an apex, w ith Hailwood more or less in charge, standing on the footrests fighting it from one gutter to the other. Then down Bray Hill, out of the saddle to haul it upright for the bump that launched him into the air at 150 mph all ready to wrestle in a straightish line away towards Quarter Bridge.

There's no reproaching people for their mythology. Certainly not in the Isle of Man. The place was rife with it, from wistful to terrifying, long before sporting types with feeble motorcycles boated over in 1907. The island obtrudes green and abrupt from the Irish Sea. The Vikings, w'ho built wooden castles later turned to forbidding stone, were among the more celebrated visitors but even they, at the turn of the millenium, must have been quite as baffled as we are by the old stuff— the standing stones, the cuneiform messages, the ragged but purposeful stone

circles in the rubbery heather of the bare hills high above the sea. The museum says this is an old and culturally remote island, the cradle of a civilization that never got much beyond the cradle.

The Isle of Man is too strange to be mistaken for a little bit of England or Ireland. You can catch odd boats from Liverpool, boats that plod up to the harbor at Douglas when the dawn is breaking. The island is discovered as much from the sky as the sea and it has a pale chill to it. You might, for example, think of those flaming funeral long boats of the Vikings drifting and incinerating till they sank. You might well. Interpretations differ, but the fact is that whenever we go to the Isle of Man for motorcycling, on boat after boat fit to sink for motorcycles, we come aw'ay bearing our dead.

Mike Hailwood began racing at Oulton Park in April 1957; he didn't win. Two months later he won the 125cc event at Castle Coombe. There was no junior class, no novice category. He was racing and beating voracious professionals. The current 250cc world champion, Cecil Standford, w;as in his first race at Oulton and when he fell off there later in the same year Hailwood was trying to beat John Surtees, the man who won the 350 title the next year. It was a good start in racing and a fair one in mythology.

Hailwood was just eighteen w'hen he first rode in the Isle of Man, in June 1958. He didn't w in there either. He didn't really need to; indeed, it might have stretched credibility a bit far. As it w'as, it was hard enough to grasp that he finished third in the 250 race behind Carlo Ubbiali and Tarquinio Provini. He had entered all four solo classes: his worst position was thirteenth in the 500cc senior. The rest of the 1958 season runs into figures: at the end of his second season Mike Hailwood was British champion in three classes, fourth in the w'orld 250cc championship, sixth in the 350, had won 74 races, and set 38 new race and lap records.

So it went on. Hailw'ood got better and the statistics of prodigy were duly chalked up. He went to the TT for the fourth time in 1961, won three classes, and lost his innocence. The senior, his hardest race, fell to him on a Manx Norton. Fine, nostalgic now, glorious. The other two were more interesting. He w;on the 125cc race and the 250cc race on borrowed machinery. The people he borrowed it from weren't entirely pleased; they had their own paid representatives in the races and they expected them to win. Nonetheless, the book says that S. M. B. Hailwood gave the Japanese their first victory in the Isle of Man and that the people he borrowed from were Honda.

The teenage sensation arrangement came to an end. Someone with business interests in Italy instructed Hailwood to ride for him. Hailwood complied. There wasn't a reason in the world why anyone should turn down the job—works rider for MV—and Count Agusta knew jt. The MVs were the world's best racing bikes. Hailwood would soon be their best rider.

There was something odd about Hailwood from the outset. His father was a millionaire. A sterling millionaire, in 1958, was a man of substance, and Stan Hailwood, who had made his money in the first of the world's great motorcycle booms, was plainly a man of substantial ego.

Before he had sensed that his son would be something extraordinary on wheels, he saw him all too clearly as something in braid—a naval officer, in fact—and sent him to Pangbourne Nautical College, an exclusive seat of learning and discipline for the sons of the brassbound gentry. Hailwood didn't like it. He liked as it happened, riding motorcycles. Stan seized the moment when it came and stood four square behind his son to an extent that Hailwood sometimes found oppressive. But Hailwood Senior made Hailwood Junior race.

The British class system is hard to understand. particularly for its victims. On a collective level, motorcycle racing is itself such a victim. It happens to be Britain's second best attended sport (after soccer), but although most national newspapers now' pay attention to it, they treat it, by and large, as a minority folly. Hailwood ran into all that . . . twice. Once when he arrived in motorcycling from the spacious, luxurious, though hardly indulgent background his father's wealth had afforded, and once when he became a car racer. First they said that Stan Hailwood bought Mike his success (and true, Stan—a motorcycle millionaire w'ho knew' a lot of peoplestopped at practically nothing to root out good equipment for his boy, and more than once bought the bike that beat him), to w hich Mike could only reply by wanning one world championship after another. And then they said, when Hailwood wriggled into a Formula One cockpit; "Awfully nice chap, you know' . . . used to be a motorcyclist." Car racing is a much worse attended but much more important sport in Britain. Motorcycle racing is a workingclass sport; this relationship is a little hard to explain.

Nonetheless, the legend, or at any rate the peculiar status of Mike Hailwood, has its roots in his social origins. He came to motorcycling from outside its traditional talent pool; he has a vaguely patrician cast, though none of his own making; he's exuberant and self-confident, prankish in the public (highly private) school manner; he plays clarinet in jazz bands, hobnobs w'ith the eccentric nobility, throw's friends in fish ponds; in short, a classic denizen of the Formula One paddock. But he had

chosen motorcycling. And at first Formula One rejected him. It was as if Hailwood had gone native. He wasn't at ease in the Formula One drawing rooms This, however interpreted through the murky pages of the British motorcycle press, quietly delighted the two-wheeled crowd. Significantly, Hailwood's defection to cars was never held against him. It was as if it didn't matter, wasn't the real man; and anyway, the bastards didn't appreciate him. His is the myth of the hero from outside, even from above. It's slightly reminiscent of T. E. Lawrence, and ever so slightly messianic. There's no point in pursuing that. But Hailwood's return to the Isle of Man as the most glamorous selfconfessed also-ran in the history of the sport has the ring of legend. The thirty thousand spare beds on the Isle of Man were spoken for in early January—three months ahead of schedule. No one knew' why. But everyone assumed it was Hailwood. There was a great flourish of idolatry on that strange, pagan island. By April, the hoteliers of Mona were importing extra beds. Add that to the myth.

Hailwood can ride a motorcycle well. He won nine world championships and twelve TTs. The TT has changed a little since 1967. This course, this 373/4-mile circuit (no one ever settles for 38, w'hatever their hurry), commands every cliché in journalism, some of them quite good. "Blood Bath Island"—from the Daily Sketch one year when six were killed; "the ultimate test of man and machine," from anybody you care to ask. Yes, and "the throttle goes both ways," they say.

Consider this circuit for a moment. Thirty-seven-and-three-quarters miles. To ride around it once is to forget every yard of it. The newcomer on a fast touring bike is a busy rider. For the first twenty-four miles there's scarcely a bend you can see around. No reason there should be: these are public roads. At fast touring speeds, the first eight miles are straightish, fairly broad road, anything up to a mighty thirty feet across. But some parts will slow you nearly to a standstill anyway: Quarter Bridge, Bradden Bridge, Union Mills, Greeba Castle. On your side of the road, you will be suitably apprehensive, wondering what's next. Past the Highlander Inn, where you can see for half a mile, and where if you care to trust no one potters out of the parking lot, you could briefly hit a hundred. Then you'll slow down, feeling cute. You'll get to the 90° turn at Ballacraine, ride off under the trees, and then, as they say in horse racing, you'll be in the country. On the third and fourth and fifth time round you'll begin to remember bits of the first bit and you'll start to go fast between the stone walls, the curbs, the pubs, the post offices, the tele-

phone boxes, the bridges, and the smattering of straw bales. Let's say that going fast, because you're a hard rider, you'll average 65 miles an hour between the Grandstand and Ballacraine. That's fast. And then when you learn that in 1977 John Williams averaged over 120 mph for that section, you'll be impressed enough to get up at 4 a.m. for early morning practice (they can't close 3734 miles of readjust anytime, even in the Isle of Man) to see something unlikely.

Everywhere's lonely at 5 a.m. Choose a slightly rainy morning, stand somewhere desolate, and wait for a man on a racing motorcycle to ride past you on that snippet of public roadway at twice the speed that every nerve in your highway-trained body says is already too fast, and see if you're disappointed.

After Ballacraine, the hard part. Fifteen miles of tortured tarmac that wriggles like that because it has to go around people's fields and between their houses, to follow the course of streams through their overhanging valleys, bob round rocks and hang on to long-forgotten rights of way. This, you would say at first glance at a picture postcard, is a fine old downhome Leafy British Lane. A frank guide will have to tell you that this place or that is where this or the other of the world's finest riders made a mistake. Herrero just there, though it's grown over again; poor Les Graham at the bottom of Bray Hill; Gilberto Parlotti up on the Mountain, where he hit the roadside marker post. (But they've moved all the posts now.)

Two miles out of Ramsey (the island's other town), you climb out of the trees and on to the moors. From the Gooseneck, a slow right-hander with a fast approach. the> spectators can see all the way to Scotland and every move a rider makes. Competitors who miss a gear there light up with a blush they'll see in Stranraer. It's no comfort that the gallery can (and does) remember the day Geoff Duke did it.

From just above the Gooseneck, you can see. Bend after bend you can see all the way round. For more than a mile, a straight so fast and so steep that on the final lap it threatens to strip every thread in the race leader's body. From then on. fast smooth roads to the Bungalow, up to Brandywell, then all downhill and fast. Two more things. One. on the way down last year, just after Creg-ny-Baa, Mick Grant's Kawasaki was timed at 191 mph. That's faster than Daytona. Two. the record lap stands at 114.33. That's faster than Daytona. Daytona is a speed bowl where 180 mph looks very impressive. This is a public road.

Mike Hailwood finally stopped racing motorcycles in 1972. Bv that time he was deeply involved with cars (he won the European Formula Two Championship in 1972), and back on two wheels everyone raced Yamahas. Hailwood tried one at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone. It puzzled him somewhat and he wasn't quite sure how to start it. They left him on the grid, but he finished sixth.

Hailwood has no fine feeling, so he says, for machinery; not a technical man. There's an amateur event around the TT circuit, the Manx Grand Prix, held in September, and after The Announcement was made. Hailwood was allowed out in the practice traffic with a fairing-mounted camera and a microphone. Yamaha arranged a TZ750D and their agents. Padgetts, took it out to Jurby airfield. Hailwood was supposed to ride it up and down. He arrived and looked at it closely.

"No." he said.

"No? No what?"

"No—I'm not riding it. Terrifying. No one should ride anything like that. I'll have a go on the 350."

He was persuaded—just up and down. Mike, no corners. Not so bad, eh? OK. Maybe just a lap. He brought it back off the Mountain with the fairing scraped and the expansion chambers flattened, and later sidled up to Peter Padgett. Peter, what's that funny lever under the twistgrip? The choke. Oh. Peter, what do you suppose ten and a half in top would be? About 160 miles an hour. Oh.

In 1974, the Armco at Nurburgring narrowly failed to tear Hailwood limb from limb, but it did stop him racing cars or anything else. He limped around motorcycling venues, including the TT, hanging about with his mates and making unexpected appearances that more than once brought applauding crowds to their feet. Again the sentiment was plain: silly cars, he shouldn't have raced them in the first place. It was their fault, not his.

Since he was 24 Hailwood has been complaining that the wear and tear have made him an old man before his time. An old man at 24 and a young one at 38. He made the decision to race in the Isle of Man because he had recovered from his injuries, he could brake with the onceshredded foot, and he couldn't think of any reason why he shouldn't. He didn't care about not winning (though he'd like to win), and he didn't care about the corrosion of the legend. Mike Hailwood doesn't believe in the legend.

Sponsors, on the other hand, do. Hailwood. even in car racing, never knew quite what to do about sponsorship. Times have changed. This time, he didn't even have to think about it. Martini, while snapping him up for their first motorcycle venture, made it clear that they wouldn't have done it for anyone else; not only did Yamaha make machinery available in three classes, but Nobby Clark, Hailwood's Honda mechanic of the sixties and late of Giacomo Agostini, stepped in hot foot to tend them (Kel Carruthers, it was said, would take time off from tweaking for Roberts to be in the Hailwood pit); Seiko watches came in. Lookwell Leathers. Castrol, Regina, and Dunlop. Dunlop told Mike, who had leaned a bike over to 61 ° in the stone age of tire development, something interesting: that whatever he had done on the neolithic covers, he could now add on 15 or 20%. He mused a little. "Wouldn't that get me round the Isle of Man at 130 miles an hour?" But he doesn't believe in the legend. He thinks it's sillv. embarrassing.

Every reason Hailwood gives for choosing the Isle of Man TT is the precise echo of the reason, say, Barry Sheene gives for striking it off the calendar: it's long; the surface changes, and the weather changes; it's dangerous; it's a race against the clock. The length, says Hailwood in rationalizing his passion for the Mountain circuit, is an irresistible test of memory and intelligence; the changing surfaces and weather (the course climbs up to 1384 feet at Brandywell) a test of judgment; the danger a test of self-discipline; the fact that two riders leave together at 10-second intervals, a test of a rider's ability to pace himself, to race against himself. But Hailwood didn't want to be tested. He wanted to enjoy.

His first race, on a production-based 900 SS Ducati prepared and managed by the Manchester dealers team Sports Motor Cycles (his first signing of the comeback, at a figure more than modest enough to suggest that money wasn't his motive), would, oddly, be both against a works Honda and against its rider, Phil Read. Read, Hailwood's age, rode in his shadow in the sixties and didn't care for it. Unlike Hailwood, Read turned on the Isle of Man and supported its loss of world championship status, but in 1977 rolled up to win two races. Read doesn't choke on humble pie; he uses it as a nerve tonic. Hailwood, among millions of others, was appalled by his behavior. He wanted to beat Read, in passing, but he wasn't proposing to kill himself to do it.

He promised nothing, except to himself to stay alive and to his sponsors to give them their money's worth. Hailwood's loyalty to his backers amounts almost to a nervous condition. He hated the Honda 500 Four on which he won world championships—for a while it was the centerpiece of his living room and even then he gave it a wide berth—and though he pleaded with the factory to forget the power and make it handle, he still rode it to the limits of his ability and a TT record lap that stood for nine years. Riding it made him depressed and cantankerous, temporarily changed his personality, but he was paid for it and he did it. A year later when Honda abandoned GP racing, he was paid not to ride it—or anything else with two wheels. That lucrative but frustrating clause drew him finally over to cars—he had to race something.

He'd been practicing in New Zealand (where he now lives) and racing in Australia. No one knew how well he'd ride. At Bathurst, on ailing machinery, he was lapped; at a local circuit he lapped in practice within a second of Gregg Hansford's record. However he rode in the Isle of Man would be the best he could possibly do, and certainly an emotional spectacle. The man from the sixties; the man in black; the man with more TTs to his credit than any other; the man who'd won everything. several times; the man who came back, as no one ever had before, from Formula One; an irrepressible man who didn't even care that he's supposed to be a legend.

Unusual stuff. His agent, journalist Ted Macauley, called Hailwood up to give him the closing details of the sponsorship arrangements:

"You're riding for Life Helmets, you know."

"Yes, so I gather." (They have motorcycle papers in New Zealand.)

"Well, they want to know if you have any special requirements, anything built into your helmet."

"No. I mean, yes. It's got to have a hole in the front."

Still not much of a technical man.

Hailwood probably never thought of changing his mind. Nonetheless, what he had bitten off began to be hard to chew. The Isle of Man was overloaded, over-subscribed. More people than ever before had shelled out to see motorcycle racing, to see Hailwood. Hailwood took it seriously, more so than he had originally intended.

At his first test session, at Oulton Park one wet day not long after dawn, he looked old, scraggy, peculiar. His hair, such as it was, was wet, lank. Hailwood, as it happens, is a strong man, with strong arms and a cluster of pectorals of the bronzed kind that beckon from get-fit ads. He is fit, but he didn't look it that day. He didn't look convincing. No one who didn't know about the myth would have believed that anything of any importance could be pinned on his polite, unlikely, rainsuited figure.

But Hailwood made a couple of interesting remarks. He sat bedraggled in the back of the Jaguar belonging to the TV personality who had come to interview him and thought about his tires, Dunlop's latest wet-weather jobs. "I just kept leaning it over and then leaning it some more. Nothing happened. I was way past the point where I should have been on my backside and sliding down the road. I don't understand it. How do they do it?" He shook his head, impressed. And he still insisted that he wasn't going to go to the Island and win.

There was, it must be said, a general feeling that it would be nice just to see Hailwood ride around the Island. In the baffled euphoria following The Announcement, people had been ready to predict that Hailwood would win. As the event came closer, there was a certain amount of backing off. That he would win became a much more privately held possibility. Sensibly speaking, it didn't really seem much of a likelihood. He was taken more readily at his word. The motorcycle papers made pre-race predictions. The best Hailwood was offered by one of them

was sixth in the Formula One. Honda Britain, meanwhile, defending the Formula One title, announced to the accompaniment of a stinging denial that they had turned Hailwood down. What they said was that Hailwood was a certain loser, a once-great rider who had no hope of meeting current standards. They might have lent him a bike for a demonstration lap. they remarked with impressive condescension, but that was all. One way and another, the scene of sincere consolation was being discreetly set.

On the first night of official practice, Hailwood took the Sports Ducati out and broke the Formula One lap record. Confidence in Hailwood took a boost. The same evening he rode his Yamaha 500 Four around at 105.70 mph. Fastest in practice in two classes.

Hailwood went faster. And then faster. By the middle of practice week he was putting the TZ750 around in excess of 110 mph. It was common, indeed quite sensible, to believe that Hailwood would win. Wise, just before the event.

While he went steadily faster on the Ducati. several others went faster still. One of them was Phil Read. On Thursday he lapped at over 109 mph. Formula One is essentially a silhouette class. Frames are a free-for-all and engine modifications are almost unrestricted. If Read's works Honda wasn't a faster bike, it should have been. A dealer-entered Vee-Twin should start and finish as the mechanical underdog and Read's time seemed decisive. Hailwood was 6 mph slower and there was a ripple of indignation that the great man should be put at such a disadvantage. But that was Thursday.

On Friday, Hailwood did something sensational. Suddenly he rode around the TT course at more than 111 mph on what amounted to a beefed-up street bike. Not only was it 2 mph faster than Read; it was just over 1 mph short of the absolute record. But the record was held by the fastest one-off racer the Kawasaki factory knew how to make. The Island was astonished, and Read was stung. Finally, just one last time, Mike Hailwood had set Phil Read's nerves clattering. It was a masterpiece of destructive psychology and Hailwood was plainly pleased with it.

Came the race and Hailwood won. By that time, because of the way the week had developed, there was no outstanding theoretical reason why he shouldn't. There was a credibility lag. All of what was happening seemed too corny to be true.

At Ballacraine on the first lap Hailwood was leading Tommy Herron, who was aboard a Mocheck/Yoshimura Honda and shaping up to win on it, by tour seconds. Hailwood held his lead, but Herron hung on a few seconds behind until, leaping the brow at Rhencullen, he broke his frame. Next man down, and well down, was Read,

riding the bike that was too good for Hailwood. Read had started fifty seconds ahead. Halfway through the third lap, Hailwood caught him on the road. They raced through Ramsey together, over the Mountain, and into the pits. Read and Hailwood. It was an eerie moment, a mass fantasy made dangerous reality because too much wishing had made it so. We were afraid to look up the road, in case our fevered imagination should bring Hartle, Hocking, an MV and a couple of works

Güeras into the pits.

Hailwood runs with a limp, and while Read hustled away the refueled Ducati was slow to fire. But Hailwood had caught up

by Ballacraine and this time he was ready to go past. He said later that it was no trouble. Read, in reply, gave the Honda its all, and blew it up. "I had to," he said later in the bar, and no doubt he was right.

Hailwood's victory was probably among the sweetest, and certainly among the most peculiar in the history of competition. The pundits silenced, Honda crushed, the

crowds ecstatic: a comeback of total perfection . . . and the myth amplified. Even when he stood on the rostrum the apparent facts strained credulity. It was a ripping yarn, a damn good bedtime story for the reasonably imaginative infant; but not the sort of stuff you serve up for adults. But they gave Hailwood the garland, and he walked away with tears in his eyes.

The rest of the week was easier on the heartstrings, although it infuriated Hailwood. He was nicely placed in the Senior (500cc) when a bushing collapsed in his steering damper. At length he had it seen to and finished twenty-eighth. On Wednesday, for the Junior (250cc), it was raining. Hailwood had found the peaky little Twin hard going and though he circulated ably and set the second fastest lap, he gave discretion plenty of elbow room and finished twelfth.

Friday was the big day. But not for Hailwood. He led the lOOOcc Classic event on his TZ750 Yamaha until Kirkmiehael on the first lap. when it began to misfire. He pottered back to the Grandstand, 25 miles away, with a broken crank. In his private comments later in the day there was much that was straightforward and a little that suggested there would be a next time: "and next time. . . ."

Hailwood had one further engagement: the traditional Post TT International at Mallory Park, which was quite a different matter. Even those who had seen him wán on the Island were doubtful of the wisdom of his scratching round Mallory with its five bends and 1 lap record under fifty seconds. The Isle of Man is a rider's circuit; but Mallory Park. . . .

Hailwood, who Huffed his start, was about fifteenth into the first bend in the Formula One race and about tenth out of it. At the end of the second lap he was third, ahead of him Phil Read on the rebuilt works Honda and John Cowie on a still faster Kawasaki. Cowie went past Read, and after a brief showing of his front w'heel, so did Hailwood. On braking for the Esses Hailwood took Cowie, right

round the outside. Hailwood won. His boots were ripped and his feet were bleeding.

By the time Hailwood w'on at Mallory.

a little over a week after he had w'on in the Isle of Man. we w^ere beginning to believe seriously in wTat we were seeing. And that made it all the more astounding. Mike Hailwood, waiting on the line at Mallory Park, saw' his wife and children not far away. You could sense the grin, though all you could see was his eyes.

So suddenly he starts to wave, one of those discreet but rather silly waves you do for children, with the w'obbly wrist action. In thirty seconds he's going to be belting into one of motor sport's hardest no-quarter bends, with two dozen nerveless men. any one of whom would crucify him to slake their own lust for competition. Him in particular. And he's weaving like something out of Sesame Street.

No winder he had Read psyched out all those years. A lot was hanging on this race. Maybe he didn't care about the legend but he had made it clear that he did care about winning.

The win was truly amazing. Because Mallory Park is the antithesis of the Isle of Man; and everything that made the TT a

reasonable venue for a Hailwood comeback made a folly of Mallory; and on a power circuit his bike w'as slower. He came out of the bends faster and lasted on the straights. Then he passed on braking. He knew all along what he had to do to win— but how could he not give the kids a w^ave? After all. they don't often get to see daddy racing motorcycles.

At the end of the w'eek of disappointment with his Yamahas Hailwood, in conversation in the hotel bar. was asked once too often, once too incoherently, for his autograph. He declined the proferred ballpoint and looked into the distance, claiming anonymity.

"But you're him—you're Hailwood.'' Drunk, and puzzled.

"No. sir. Though I am often mistaken for him."

"But you're Mike the Bike." Losing confidence. "Aren't you?"

"No, sir. Though I must say I wish I w^as. Yes, I wish I was."

Mike Hailwood. 38. marine-engine concessionaire of Christchurch, New' Zealand, is married with two children. His hobbies include swimming, music, and motorcycling.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue