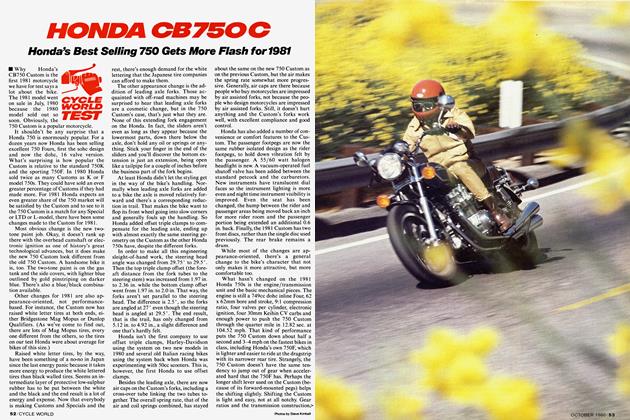

HARLEY DAVIDSON FLH80

CYCCLE WORLD TEST

by Henry N. Manney III

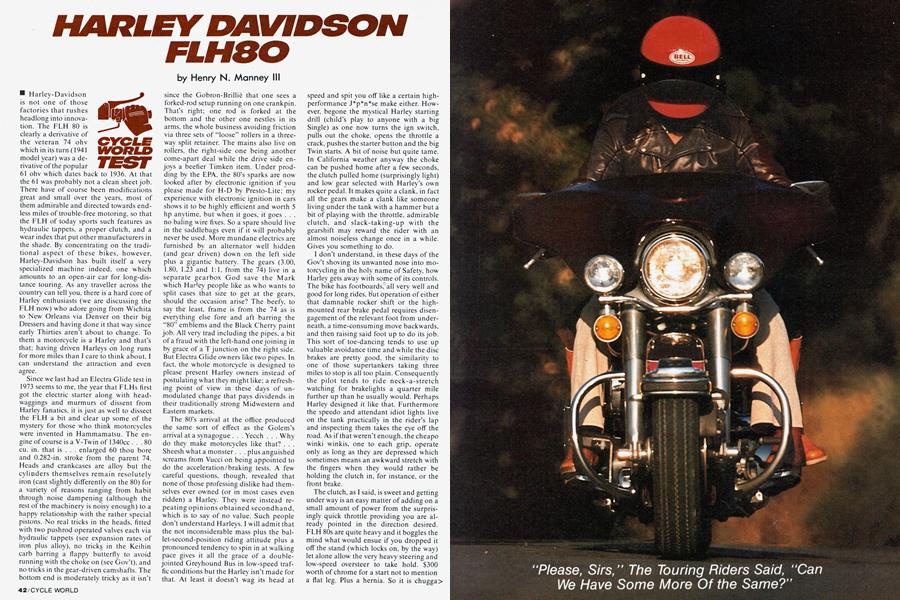

Harley-Davidson is not one of those factories that rushes headlong into innovation. The FLH 80 is clearly a derivative of the veteran 74 ohv which in its turn (1941 model year) was a derivative of the popular

61 ohv which dates back to 1936. At that the 61 was probably not a clean sheet job. There have of course been modifications great and small over the years, most of them admirable and directed towards endless miles of trouble-free motoring, so that the FLH of today sports such features as hydraulic tappets, a proper clutch, and a wear index that put other manufacturers in the shade. By concentrating on the traditional aspect of these bikes, however, Harley-Davidson has built itself a very specialized machine indeed, one which amounts to an open-air car for long-distance touring. As any traveller across the country can tell you, there is a hard core of Harley enthusiasts (we are discussing the FLH now) who adore going from Wichita to New Orleans via Denver on their big Dressers and having done it that way since early Thirties aren’t about to change. To them a motorcycle is a Harley and that’s that; having driven Harleys on long runs for more miles than I care to think about, I can understand the attraction and even agree.

Since we last had an Electra Glide test in 1973 seems to me, the year that FLHs first got the electric starter along with headwaggings and murmurs of dissent from Harley fanatics, it is just as well to dissect the FLH a bit and clear up some of the mystery for those who think motorcycles were invented in Hammamatsu. The engine of course is a V-Twin of 1340cc ... 80 cu. in. that is . . . enlarged 60 thou bore and 0.282-in. stroke from the parent 74. Heads and crankcases are alloy but the cylinders themselves remain resolutely iron (cast slightly differently on the 80) for a variety of reasons ranging from habit through noise dampening (although the rest of the machinery is noisy enough) to a happy relationship with the rather special pistons. No real tricks in the heads, fitted with two pushrod operated valves each via hydraulic tappets (see expansion rates of iron plus alloy), no tricks in the Keihin carb barring a flappy butterfly to avoid running with the choke on (see Gov’t), and no tricks in the gear-driven camshafts. The bottom end is moderately tricky as it isn’t since the Gobron-Brillié that one sees a forked-rod setup running on one crankpin. That’s right; one rod is forked at the bottom and the other one nestles in its arms, the whole business avoiding friction via three sets of “loose” rollers in a threeway split retainer. The mains also live on rollers, the right-side one being another come-apart deal while the drive side enjoys a beefier Timken item. Under prodding by the EPA, the 80’s sparks are now looked after by electronic ignition if you please made for H-D by Presto-Lite; my experience with electronic ignition in cars shows it to be highly efficient and worth 5 hp anytime, but when it goes, it goes . . . no baling wire fixes. So a spare should live in the saddlebags even if it will probably never be used. More mundane electrics are furnished by an alternator well hidden (and gear driven) down on the left side plus a gigantic battery. The gears (3.00, 1.80, 1.23 and 1:1, from the 74) live in a separate gearbox God save the Mark which Har'ey people like as who wants to split cases that size to get at the gears, should the occasion arise? The beefy, to say the least, frame is from the 74 as is everything else fore and aft barring the “80” emblems and the Black Cherry paint job. All very trad including the pipes, a bit of a fraud with the left-hand one joining in by grace of a T junction on the right side. But Electra Glide owners like two pipes. In fact, the whole motorcycle is designed to please present Harley owners instead of postulating what they might like; a refreshing point of view in these days of unmodulated change that pays dividends in their traditionally strong Midwestern and Eastern markets.

The 80’s arrival at the office produced the same sort of effect as the Golem’s arrival at a synagogue . . . Yecch . . . Why do they make motorcycles like that? . . . Sheesh what a monster . . . plus anguished screams from Vucci on being appointed to do the acceleration/braking tests. A few careful questions, though, revealed that none of those professing dislike had themselves ever owned (or in most cases even ridden) a Harley. They were instead repeating opinions obtained secondhand, which is to say of no value. Such people don’t understand Harleys. I will admit that the not inconsiderable mass plus the ballet-second-position riding attitude plus a pronounced tendency to spin in at walking pace gives it all the grace of a doublejointed Greyhound Bus in low-speed traffic conditions but the Harley isn’t made for that. At least it doesn’t wag its head at speed and spit you off like a certain highperformance J*p*n*se make either. However, begone the mystical Harley starting drill (child’s play to anyone with a big Single) as one now turns the ign switch, pulls out the choke, opens the throttle a crack, pushes the starter button and the big Twin starts. A bit of noise but quite tame. In California weather anyway the choke can be pushed home after a few seconds, the clutch pulled home (surprisingly light) and low gear selected with Harley’s own rocker pedal. It makes quite a clank, in fact all the gears make a clank like someone living under the tank with a hammer but a bit of playing with the throttle, admirable clutch, and slack-taking-up with the gearshift may reward the rider with an almost noiseless change once in a while. Gives you something to do.

I don’t understand, in these days of the Gov’t shoving its unwanted nose into motorcycling in the holy name of Safety, how Harley gets away with some of its controls. The bike has footboards, all very well and good for long rides, but operation of either that damnable rocker shift or the highmounted rear brake pedal requires disengagement of the relevant foot from underneath, a time-consuming move backwards, and then raising said foot up to do its job. This sort of toe-dancing tends to use up valuable avoidance time and while the disc brakes are pretty good, the similarity to one of those supertankers taking three miles to stop is all too plain. Consequently the pilot tends to ride neck-a-stretch watching for brakelights a quarter mile further up than he usually would. Perhaps Harley designed it like that. Furthermore the speedo and attendant idiot lights live on the tank practically in the rider’s lap and inspecting them takes the eye off the road. As if that weren’t enough, the cheapo winki winkis, one to each grip, operate only as long as they are depressed which sometimes means an awkward stretch with the fingers when they would rather be holding the clutch in, for instance, or the front brake.

The clutch, as I said, is sweet and getting under way is an easy matter of adding on a small amount of power from the surprisingly quick throttle providing you are already pointed in the direction desired. FLH 80s are quite heavy and it boggles the mind what would ensue if you dropped it off the stand (which locks on, by the way) let alone allow the very heavy steering and low-speed oversteer to take hold. $300 worth of chrome for a start not to mention a flat leg. Plus a hernia. So it is chugga> chugga Bong Chugga chugga Bong etc; actually the rider gets used to the FLH quickly in traffic as with its low center of gravity and fat tires it tends to hold an upright stable posture while gliding to a halt. Riders with short legs are going to have a terrible time, even though the riding position seems to be designed for someone 5'3" and measuring 30" across the pelvis, as the 5-gal. “Fat Bob” tank, exceptional engine width, and protruding footboards mean that I am, at 6 ft., standing on tippy toes at rest. The Harley seat is a marvellous device on its sprung pillar, concealing underneath an equally marvellous linkage that provides an extra set-up for what used to be called buddy riding (more’s the pity that the whole gemilla is held on with two hose clamps) but it does perch the occupant way up in the air.

"Please, Sirs," The Touring Riders Said, "Can We Have Some More Of the Same?"

Details. Millions of contented riders have driven Harleys across the country and that is the sort of thing that Harley does best. Briskly massaging the gearbox to get out of town and on the highway produces useful acceleration a la traffic cop but the bike appears to go just as well with moderate throttle and a drop into top gear as soon as practicable, say 40 mph. Then the giant bore and giant stroke and all that lovely torque take over to produce a most satisfying waffling beat from the big Twin that wafts the outfit effortlessly down the highway, doing seemingly about 800 rpm. There is a little vibration under normal operation but no particular vibration period appears, up the range till you get to 75 approx, although the engine smooths out marvellously in the region of 60-70 which by happenstance used to be the speed limit before the Gov’t used Arabs as an excuse to shut us down. Designed as it is for carrying a couple plus baggage across long distances, the FLH 80 pays no particular interest in mountain grades or otherwise and for that matter, is just as stable (i.e. like a rock) on mountain bends as it is on a dead straight road so long as too great an angle of lean is not employed. Bumpy bends can set up a gentle wallowing, probably encouraged by the pillar-sprung seat and the drooped bars, but like those old trainer biplanes the Harley can undoubtedly fly itself, given the chance. I don’t care much for the riding position, sitting with legs spread apart and bent over to hold those bars, but you might like it. Comfortwise, in spite of the Neanderthal front forks and the rear shocks being at the front end of the swing arm to clear the saddlebags, the FLH 80’s fat whitewall tires mounted on stylish alloy wheels smooth out the road in impressive fashion. Rain grooves and similar manifestations of the paver’s art have little or no effect. A badly cut-up surface, however, reminds one that Harley has never heard of the theory of unsprung vs sprung weight, i.e., those ornamental chrome doodads on each end of the front axle which weigh almost 200 grams (abt 7 oz) each. In spite of a rather poor finish on the fiberglass, both fairing (which resonates a little at times) and saddlebags make life much much easier on the road and although we made one run of about 200 miles, a longer one would be quite interesting. The big Twin idled faultlessly, ran reliably, never got hot, cured its own sticky tappet and only used one of the

four quarts from its filtered dry sumped tank, most of that I suspect courtesy the rear chain oiler. The bike is very handsome and well finished off, drawing admiring looks from not only other Harley riders but smiling gents in big cars who are just apt to say “I useter have one like that”. With a Harley you are in another mode of life from “normal” motorcycling and, to be honest, a very pleasant and relaxed one. Vancouver, here we come! > For such a heavy machine, the stock shocks do an admirable job, at least for the solo rider. Adjusting the spring preload will compensate for most variations in laden weight, but the damping is not proportional to the scaled-up size of the machine. For additional control when the bike is heavily laden, a set of aftermarket shocks with extra firm damping would be advantageous. S3

HARLEY DAVIDSON

FLH80

$4905

Because of the size of the FLH, its front suspension yields a fairly soft ride. Static seal friction is unusually high, but effectively supplements the forks’ relatively low damping rates. The fork springs, preloaded at nearly 80 lb., are not as stiff as one might expect, and allow utilization of the available travel with no bottoming or topping.

Tests performed at Number 1 Products

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontYou Can't Take the Harley Out of the Boy

October 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Departments

DepartmentsBook News

October 1978 By A.G., Chuck Johnston, Michael M. Griffin -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1978 -

Short Strokes

October 1978 By Tim Barela -

Technical

TechnicalYamaha It250/400 Steering Fix

October 1978 By Len Vucci