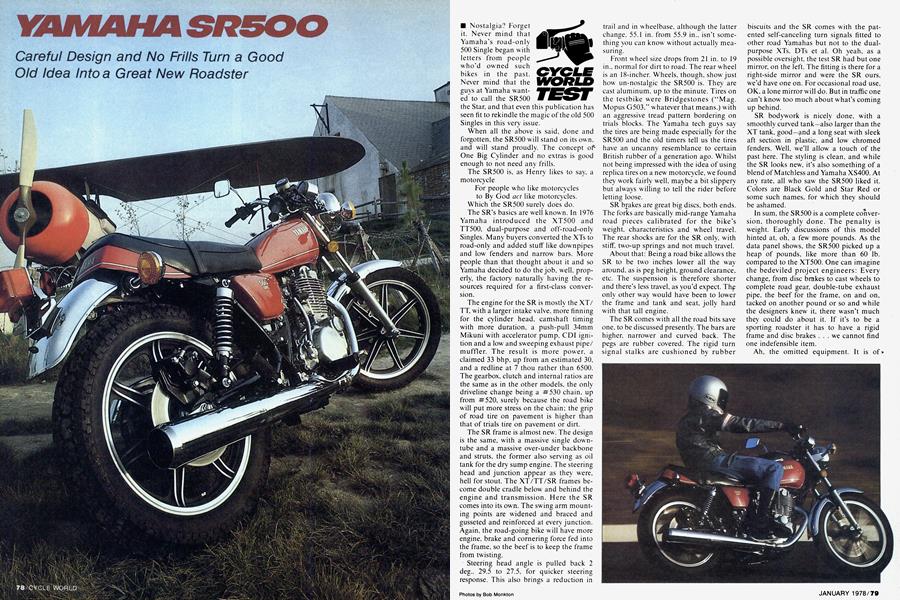

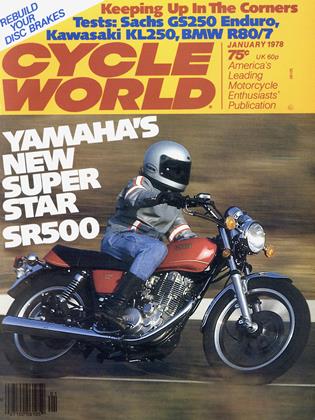

YAMAHA SR500

Careful Design and No Frills Turn a Good Old Idea Into a Great New Roadster

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Nostalgia? Forget it. Never mind that Yamaha’s road-only 500 Single began with letters from people who’d owned such bikes in the past.

Never mind that the guys at Yamaha wanted to call the SR500 the Star, and that even this publication has seen fit to rekindle the magic of the old 500 Singles in this very issue.

When all the above is said, done and forgotten, the SR500 will stand on its own. and will stand proudly. The concept of One Big Cylinder and no extras is good enough to not need any frills.

The SR500 is, as Henry likes to say, a motorcycle

For people who like motorcycles

to By God act like motorcycles.

Which the SR500 surely does do.

The SR’s basics are well known. In 1976 Yamaha introduced the XT500 and TT500, dual-purpose and off-road-only Singles. Many buyers converted the XTs to road-only and added stuff like downpipes and low fenders and narrow bars. More people than that thought about it and so Yamaha decided to do the job, well, properly, the factory naturally having the resources required for a first-class conversion.

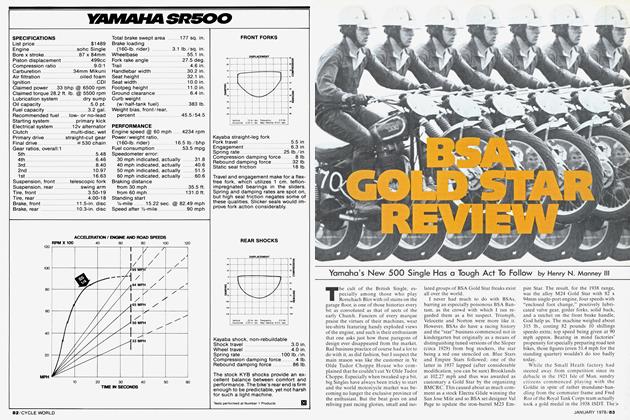

The engine for the SR is mostly the XT/ TT, with a larger intake valve, more finning for the cylinder head, camshaft timing with more duration, a push-pull 34mm Mikuni with accelerator pump, CDI ignition and a low and sweeping exhaust pipe/ muffler. The result is more power, a claimed 33 bhp, up from an estimated 30. and a redline at 7 thou rather than 6500. The gearbox, clutch and internal ratios are the same as in the other models, the only driveline change being a #530 chain, up from #520, surely because the road bike will put more stress on the chain; the grip of road tire on pavement is higher than that of trials tire on pavement or dirt.

The SR frame is almost new. The design is the same, with a massive single downtube and a massive over-under backbone and struts, the former also serving as oil tank for the dry sump engine. The steering head and junction appear as they were, hell for stout. The XT/TT/SR frames become double cradle below and behind the engine and transmission. Here the SR comes into its own. The swing arm mounting points are widened and braced and gusseted and reinforced at every junction. Again, the road-going bike will have more engine, brake and cornering force fed into the frame, so the beef is to keep the frame from twisting.

Steering head angle is pulled back 2 deg.. 29.5 to 27.5, for quicker steering response. This also brings a reduction in trail and in wheelbase, although the latter change, 55.1 in. from 55.9 in., isn’t something you can know without actually measuring.

Front wheel size drops from 21 in. to 19 in., normal for dirt to road. The rear wheel is an 18-incher. Wheels, though, show just how un-nostalgic the SR500 is. They are cast aluminum, up to the minute. Tires on the testbike were Bridgestones (“Mag. Mopus G503,” whatever that means.) with an aggressive tread pattern bordering on trials blocks. The Yamaha tech guys say the tires are being made especially for the SR500 and the old timers tell us the tires have an uncanny resemblance to certain British rubber of a generation ago. Whilst not being impressed with the idea of using replica tires on a new motorcycle, we found they work fairly well, maybe a bit slippery but always willing to tell the rider before letting loose.

SR brakes are great big discs, both ends. The forks are basically mid-range Yamaha road pieces calibrated for the bike’s weight, characteristics and wheel travel. The rear shocks are for the SR only, with stiff, two-up springs and not much travel.

About that; Being a road bike allows the SR to be two inches lower all the way around, as is peg height, ground clearance, etc. The suspension is therefore shorter and there's less travel, as you’d expect. Th^ only other way would have been to lower the frame and tank and seat, jolly hard with that tall engine.

The SR comes with all the road bits save one, to be discussed presently. The bars are higher, narrower and curved back. The pegs are rubber covered. The rigid turn signal stalks are cushioned by rubber biscuits and the SR comes with the patented self-canceling turn signals fitted to other road Yamahas but not to the dualpurpose XTs, DTs et al. Oh yeah, as a possible oversight, the test SR had but one mirror, on the left. The fitting is there for a right-side mirror and were the SR ours, we’d have one on. For occasional road use, OK, a lone mirror will do. But in traffic one can’t know too much about what’s coming up behind.

SR bodywork is nicely done, with a smoothly curved tank—also larger than the XT tank, good—and a long seat with sleek aft section in plastic, and low chromed fenders. Well, we’ll allow a touch of the past here. The styling is clean, and while the SR looks new, it’s also something of a blend of Matchless and Yamaha XS400. At any rate, all who saw the SR500 liked it. Colors are Black Gold and Star Red or some such names, for which they should be ashamed.

In sum, the SR500 is a complete conversion, thoroughly done. The penalty is weight. Early discussions of this model hinted at, oh, a few more pounds. As the data panel shows, the SR500 picked up a heap of pounds, like more than 60 lb. compared to the XT500. One can imagine the bedeviled project engineers; Every change, from disc brakes to cast wheels to complete road gear, double-tube exhaust pipe, the beef for the frame, on and on, tacked on another pound or so and while the designers knew it, there wasn’t much they could do about it. If it’s to be a sporting roadster it has to have a rigid frame and disc brakes ... we cannot find one indefensible item.

Ah, the omitted equipment. It is of > course electric starting. Kick only for the SR500. The engineers did look at electric start and they say they could have done it, for more money and another 25-30 lb. and a loss in sporting character. So instead they kept the XT/TT’s compression release and piston indicator window and added a button on the carb which cracks the throttle exactly as far as their tests show it should be open when the engine is hot.

Better get this whole subject out of the way. One of the more Sybaritic members of the staff, a man who didn’t notice the kick starter is no longer permanently attached to the BMW because it’s never occurred to him to use anything other than the little button, stumbled onto the rest of us while we were experimenting with the SR’s starting characteristics. “You guys think that’s fun, huh? Why?’’

Because it just is, that’s why. A big Single is always hard to start, so doing it right is a test of skill, a game, a way to separate true believers from the dabblers like him.

Having said that, we must add that several of the crew had trouble starting the SR500 on several occasions. The test bike was new and stiff. We weren’t familiar w ith it. For emotional reasons—who wants to admit he knows less about throttle position than a dumb button knows?—some of the riders didn’t use the button. Fill in any other alibi that comes to mind, point is, big Singles can be touchy and when the mood is on one it will give the rider fits.

Now' then. Under no circumstances do we wish to discourage a potential SR500 buyer. But we w'ould be remiss if we skipped over this subject and buyers later reported they have trouble kicking the big lug into action.

So. Pop quiz time. You own an SR500. You’re out riding and stop for lunch. Is the picture in your mind? Here you come, walking up to the bike. You turn on the switch, throw’ a leg over, check to be sure it’s in neutral. . . what now? If you see the engine roaring on the first kick while the crowd goes wild, you will have no trouble. If you imagined frustration, if you saw' yourself parked on a hill just in case, perhaps electric starting should be in your future.

Our in-house mystic says the secret is vibrations. Just as you can’t win gambling with scared money, just as dogs can smell fear, so will a Thumper not start if it senses you're afraid it won’t start. Enough of that.

Enough because a big Single is like enduros, graduate study and childbirth; the rewards are so great that once the pain is over it fades from memory. When the lone cylinder goes to w ork the rider know s, here is an Engine. The feds may be able to stifle the music but they can’t legislate away the soul. The SR’s power comes in evenly spaced thuds, b-b-b-boom. Oh, it’s fine.

Disregard the figures. Actual performance isn’t the key here, so it’s of small consequence that, keeping w ithin the family, the Yamaha RD400 and XS500 both will dust the SR at the drags. So will other 500s, so will a few 400s. The added three bhp doesn’t quite equal out the extra 60 lb. XT and SR will run close to dead heat, assuming both motors are broken in and in proper tune. Our SR was just barely run in enough to be run wide open. We expect a fraction of a second could be trimmed from the drag times and another mph or two tacked onto the top speed with another 1000 miles or so rolled up.

Numbers aside, what comes through when riding the SR500 is a great pulsing beast, a flood tide of torque, a muffled throb and a willingness to pull. Rolling on the power is something the rider does because it feels good. What other reason is there?

The limits are the result of one large cylinder. The only place you can get an appreciably larger cylinder is from HarleyDavidson and that motor has another of equal giantness to balance it. The SR cylinder has lots of displacement to fill and it is rough at the low end of the engine’s rev range. The idle has a charm of its own, a rolling lope. From 1800 to about 3000 rpm the SR is even and rough and there’s a shake whenever the throttle is wide open, no matter what the speed.

However. From 3500 up. on light throttle or cruise, the SR500 is much smoother than we expected. How Yamaha has done it we can’t say, but once into the wide powerband, the Single has no more vibration than several Twfins in the same displacement range. The grips are very nearly smooth and what comes through the pegs and seat is more of a buzz than a shake. Pleasant surprise. It also makes one wonder about all this flap from the new Twins, counter-rotating shafts and opposed crankshaft throws and all the rest. A Four is twice as smooth as a Twin. A Tw in is not much smoother than a Single done right.

The road-going Thumper is an idea whose time has returned.

The limits here come from the engine’s size and nature. What a multi-cylinder 500 has is small pistons and a short stroke, íe. plenty rpm. This lets the engineers gear for high rpm-per-mile and the engine hums right along with a choice of gears for road speeds; you can trickle along in top. say. or rev past a period of resonance.

Not so with the SR500. Gearing for 90plus at redline also means roughness in top at less than 45 mph. Making first gear useful in traffic means it must be relativelv

tall, that is, low numerically. As an incidental change that came with GDI. the SR has a heavier flywheel than does the XT/ TT. The SR will move from rest at low rpm provided the rider pays attention to the engine and the clutch, else it stalls and the rider feels foolish. One is seldom conscious of this—how rare to have a comfort range narrower than the powerband! in the intermediate gears. What comes through is a shudder and clank if top gear is selected at less than 40 mph or so. In city traffic, third or fourth see much more service than they would for a smaller Single or a Multi, for which 3500 in top is likely to be 35 mph.

The SR trades back on the open road, w here 60 mph comes at 4500. The engine is happy, just shy of torque peak and thus ready for instant power and the rider wicks on down the road, floating on a muffled boom and just enough tingle to remind him that making all this happen is a good ol’ motorcycle engine. Out where the curves are. the engine is more apt to be at higher revs, great sweeping bursts between corners and all that, and the gearing is never noticed. Pick the right one and all falls into place.

The SR500 brakes can do their job with one caliper behind their backs. The stopping distances tell only part of the story, as both the XT and SR will stop in a short distance, the actual distance being controlled bv traction. The disc brakes are more easily controlled, while the XT has less weight on the front wheel at rest, so the two models stop in equal distance.

The first few times. Where the discs will pay off is on fast runs w ith tight turns. The disc brakes are huge, obviously designed initially for a bigger machine. (The right slider has bosses for a second caliper, even.) We can’t imagine the circumstances under which these units can be faded. They’ll keep on squeezing long after drum brakes have turned into cinders.

Handling? Flawless. No kidding. Imagine the unlikely mixture of the jack rabbit agility of a Yamaha RD or Ducati GT and the locomotive stability of the Laverda Jota or Kawasaki KZ 1000. Or. at the risk of salting an emotional scar, the feel of. yes, the classic English roadster. By Gad Sirs, it works. What shows as weight on the scales comes through on the road as strength. This is a narrow engine and thus a narrow motorcycle. Elsew here in this issue there is a discussion of cornering, in which it’s revealed that one “g” cornering leans the motorcycle at 45 deg. One g is race talk and the SR won’t touch down until it's beyond 45 deg., not unless the rider goes sharp at the apex on a tight turn with positive camber. The. uh. different Bridgestones will begin to scrub before that happens, for us mortal riders, anyway. Flat out the SR500 is rock steady and string straight. At no time did we feel any wobble in any mode, although the rear shocks may be a bit overburdened at full cornering speed and full power. There is a trace of working sideways, but because that comes from the shocks themselves and not from a frame unable to keep things in line, it doesn’t count here as a flaw beyond repair.

Now. a cool-off lap. The SR500 is not a touring bike. The buzz will make itself known. The seat slopes forward and is overly firm. So is the suspension unless it’s being used. Servicing a Single with CDI ignition will be child's play, except it’s awkward to be forced to remove the air cleaner to top the rear brake reservoir and to unbolt various little bits so you can slide the battery out of the frame for refreshment.

The SR500 makes demands of its own, as with starting the engine and keeping the engine in its happy range. There will be those who think it’s a throwback to the past and will buy it for that reason.

Could be a question of age and attitude. The Yamaha SR500 is now what the old 500 Single roadster could have been but never quite managed to become. It’s all the Sport and none of the Suffering. For every buyer whose past gets improved with an SR500 there will be a buyer or two who will enjoy and appreciate without ever knowing that the road-going Thumper is an idea whose time has returned. >

YAMAHA SR500

$1489

Travel and engagement make for a flexfree fork, which utilizes 1 cm. teflonimpregnated bearings in the sliders. Spring and damping rates are spot on, but high seal friction negates some of these qualities. Slicker seals would improve fork action considerably.

The stock KYB shocks provide an excellent balance between comfort and performance. The bike’s rear end is firm enough to be predictable, yet not harsh for such a light machine.

Tests performed at Number 1 Products

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Day the Blue Meanies Stayed Home

January 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

January 1978 By Chuck Johnston -

Short Strokes

January 1978 By Tim Barela -

Features

FeaturesBsa Gold Star Review

January 1978 By Henry N. Manney III -

Competition

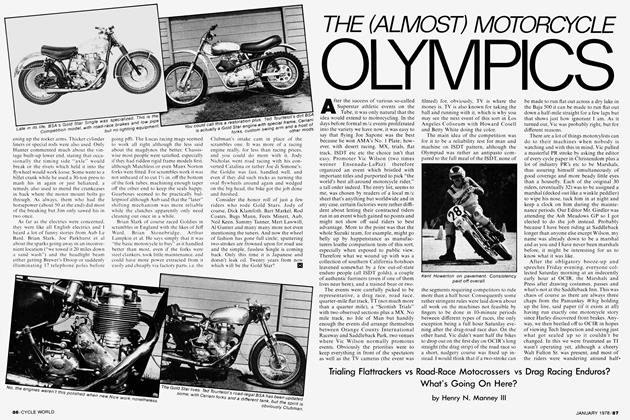

CompetitionThe (almost) Motorcycle Olympics

January 1978 By Henry N. Manney III