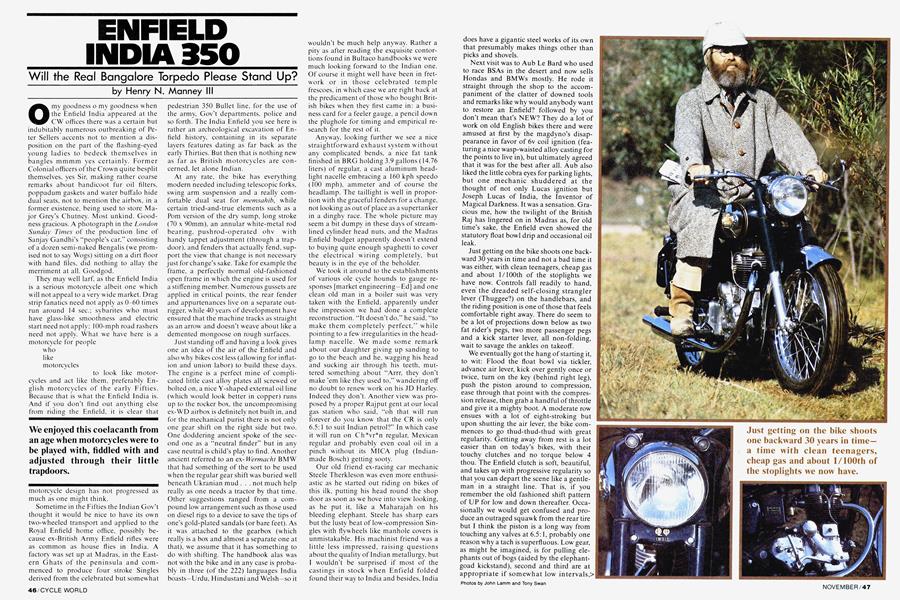

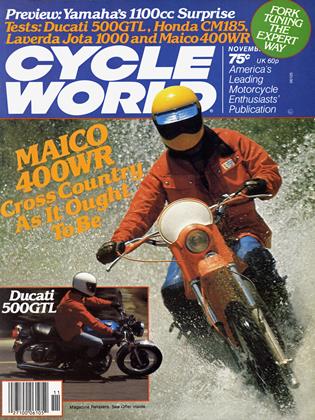

ENFIELD INDIA 350

Will the Real Bangalore Torpedo Please Stand Up?

Henry N. Manney III

O my goodness o my goodness when the Enfield India appeared at the CW offices there was a certain but indubitably numerous outbreaking of Peter Sellers accents not to mention a disposition on the part of the flashing-eyed young ladies to bedeck themselves in bangles mmmm yes certainly. Former Colonial officers of the Crown quite besplit themselves, yes Sir, making rather coarse remarks about bandicoot fur oil filters, poppadum gaskets and water buffalo hide dual seats, not to mention the airbox, in a former existence, being used to store Major Grey’s Chutney. Most unkind. Goodness gracious. A photograph in the London Sunday Times of the production line of Sanjay Gandhi’s “people’s car,” consisting of a dozen semi-naked Bengalis (we promised not to say Wogs) sitting on a dirt floor with hand files, did nothing to allay the merriment at all. Goodgod.

They may well larf, as the Enfield India is a serious motorcycle albeit one which will not appeal to a very w ide market. Drag strip fanatics need not apply as 0-60 times run around 14 sec.; sybarites who must have glass-like smoothness and electric start need not apply; 100-mph road rashers need not apply. What we have here is a motorcycle for people who like

motorcycles

to look like motorcycles and act like them, preferably English motorcycles of the early Fifties. Because that is what the Enfield India is. And if you don’t find out anything else from riding the Enfield, it is clear that

motorcycle design has not progressed as much as one might think.

We enjoyed this coelacanth from an age when motorcycles were to be played with, fiddled with and adjusted through their little trapdoors.

Sometime in the Fifties the Indian Gov’t thought it would be nice to have its own two-wheeled transport and applied to the Royal Enfield home office, possibly because ex-British Army Enfield rifles w'ere as common as house flies in India. A factory was set up at Madras, in the Eastern Ghats of the peninsula and commenced to produce four stroke Singles derived from the celebrated but somewhat pedestrian 350 Bullet line, for the use of the army, Gov’t departments, police and so forth. The India Enfield you see here is rather an archeological excavation of Enfield history, containing in its separate layers features dating as far back as the early Thirties. But then that is nothing new as far as British motorcycles are concerned, let alone Indian.

At any rate, the bike has everything modern needed including telescopic forks, swing arm suspension and a really comfortable dual seat for memsahib, while certain tried-and-true elements such as a Pom version of the dry sump, long stroke (70 x 90mm), an annular white-metal rod bearing, pushrod-operated ohv with handy tappet adjustment (through a trapdoor), and fenders that actually fend, support the view that change is not necessary just for change’s sake. Take for example the frame, a perfectly normal old-fashioned open frame in which the engine is used for a stiffening member. Numerous gussets are applied in critical points, the rear fender and appurtenances live on a separate outrigger. w hile 40 years of development have ensured that the machine tracks as straight as an arrow and doesn't weave about like a demented mongoose on rough surfaces.

Just standing off and having a look gives one an idea of the air of the Enfield and also why bikes cost less (allow ing for inflation and union labor) to build these days. The engine is a perfect mine of complicated little cast alloy plates all screwed or bolted on. a nice Y-shaped external oil line (which would look better in copper) runs up to the rocker box. the uncompromising ex-WD airbox is definitely not built in, and for the mechanical purist there is not only one gear shift on the right side but two. One doddering ancient spoke of the second one as a “neutral finder” but in any case neutral is child's play to find. Another ancient referred to an ex-ITermacbt BMW that had something of the sort to be used w hen the regular gear shift was buried well beneath Ukranian mud . . . not much help really as one needs a tractor by that time. Other suggestions ranged from a compound low' arrangement such as those used on diesel rigs to a device to save the tips of one’s gold-plated sandals (or bare feet). As it was attached to the gearbox (which really is a box and almost a separate one at that), we assume that it has something to do with shifting. The handbook alas was not with the bike and in any case is probably in three (of the 222) languages India boasts—Urdu, Hindustani and Welsh—so it wouldn’t be much help anyw'ay. Rather a pity as after reading the exquisite contortions found in Bultaco handbooks we were much looking forward to the Indian one. Of course it might well have been in fretwork or in those celebrated temple frescoes, in which case we are right back at the predicament of those who bought British bikes when they first came in: a business card for a feeler gauge, a pencil down the plughole for timing and empirical research for the rest of it.

Anyway, looking further we see a nice straightforward exhaust system without any complicated bends, a nice fat tank finished in BRG holding 3.9 gallons (14.76 liters) of regular, a cast aluminum headlight nacelle embracing a 160 kph speedo (100 mph). ammeter and of course the headlamp. The taillight is well in proportion with the graceful fenders for a change, not looking as out of place as a supertanker in a dinghy race. The whole picture may seem a bit dumpy in these days of streamlined cylinder head nuts, and the Madras Enfield budget apparently doesn't extend to buying quite enough spaghetti to cover the electrical wiring completely, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

We took it around to the establishments of various ole cycle hounds to gauge responses [market engineering—Ed] and one clean old man in a boiler suit w'as very taken with the Enfield, apparently under the impression we had done a complete reconstruction. “It doesn't do.” he said, “to make them completely perfect,” while pointing to a few' irregularities in the headlamp nacelle. We made some remark about our daughter giving up sanding to go to the beach and he, wagging his head and sucking air through his teeth, muttered something about “Arrr, they don’t make ’em like they used to,” wandering off no doubt to renew' work on his JD Harley. Indeed they don’t. Another view was proposed by a proper Rajput gent at our local gas station who said, “oh that will run forever do you know' that the CR is only 6.5:1 to suit Indian petrol?” In which case it w'ill run on Ch*vr*n regular, Mexican regular and probably even coal oil in a pinch without its MICA plug (Indianmade Bosch) getting sooty.

Our old friend ex-racing car mechanic Steele Therkleson was even more enthusiastic as he started out riding on bikes of this ilk, putting his head round the shop door as soon as we hove into view looking, as he put it, like a Maharajah on his bleeding elephant. Steele has sharp ears but the lusty beat of low-compression Singles with flywheels like manhole covers is unmistakable. His machinist friend was a little less impressed, raising questions about the quality of Indian metallurgy, but I wouldn't be surprised if most of the castings in stock when Enfield folded found their way to India and besides, India does have a gigantic steel works of its own that presumably makes things other than picks and shovels.

Next visit was to Aub Le Bard who used to race BSAs in the desert and now sells Hondas and BMWs mostly. He rode it straight through the shop to the accompaniment of the clatter of downed tools and remarks like why would anybody want to restore an Enfield? followed by you don’t mean that’s NEW? They do a lot of work on old English bikes there and were amused at first by the magdyno’s disappearance in favor of 6v coil ignition (featuring a nice wasp-waisted alloy casting for the points to live in), but ultimately agreed that it was for the best after all. Aub also liked the little cobra eyes for parking lights, but one mechanic shuddered at the thought of not only Lucas ignition but Joseph Lucas of India, the Inventor of Magical Darkness. It was a sensation. Gracious me, how the twilight of the British Raj has lingered on in Madras as, for old time’s sake, the Enfield even showed the statutory float bowl drip and occasional oil leak.

Just getting on the bike shoots one backward 30 years in time and not a bad time it was either, with clean teenagers, cheap gas and about 1/100th of the stoplights we have now. Controls fall readily to hand, even the dreaded self-closing strangler lever (Thuggee?) on the handlebars, and the riding position is one of those that feels comfortable right away. There do seem to be a lot of projections down below as two fat rider’s pegs, two more passenger pegs and a kick starter lever, all non-folding, wait to savage the ankles on takeoff.

We eventually got the hang of starting it, to wit: Flood the float bowl via tickler, advance air lever, kick over gently once or twice, turn on the key (behind right leg), push the piston around to compression, ease through that point with the compression release, then grab a handful of throttle and give it a mighty boot. A moderate row ensues with a lot of eight-stroking but upon shutting the air lever, the bike commences to go thud-thud-thud with great regularity. Getting away from rest is a lot easier than on today’s bikes, with their touchy clutches and no torque below 4 thou. The Enfield clutch is soft, beautiful, and takes up with progressive regularity so that you can depart the scene like a gentleman in a straight line. That is, if you remember the old fashioned shift pattern of UP for low and down thereafter. Occasionally we would get confused and produce an outraged squawk from the rear tire but I think the piston is a long way from touching any valves at 6.5:1, probably one reason why a tach is superfluous. Low gear, as might be imagined, is for pulling elephants out of bogs (aided by the elephantgoad kickstand), second and third are at appropriate if somewhat low intervals,>

while fourth is quite high but on the other hand good down to about 30 kph. such is the virtue of long stroke engines with flywheels out of Norwegian fishing boats. The gearbox itself is an absolute joy and when some little kid with chipped teeth pedalled up and wanted to know if the Enfield was better than a Honda, Steele replied accurately that it didn't grate its gears and you could find neutral with your eyes shut.

Under way of course the whole operation is very straightforward. Whereas nobody is going to suffer from whiplash on acceleration, the Enfield manages to keep up very well and. in fact, does better if not forced up to what passes for the high rev range. On India's largely unmade roads a lot of easy torque is needed rather than 9 thou so it is no surprise that aided by the generous l in. (25.4mm) Villiers carb the torque curve probably goes like a Model T's, straight up from 800 rpm. According to a British journal, max revs are some 700 rpm over what the bike will do flat out in top (70 mph approx.) so like a VW. long life is expected. Pottering along the back streets is sheer pleasure with that hollow. relaxed vintage exhaust note while on the freeway, oddly enough, the Single is no less adaptable. The cast alloy headlamp nacelle serves to deflect a certain amount of breeze, the fat tank serves to locate the knees as the cases are narrow, and the engine is remarkably smooth and not a shaker at all. in fact as smooth as the average 750 Twin. Piston speed being up. acceleration at these speeds is quite good and it shows no sign of running out of breath at 65 mph. Riding position was just right for me. handling first class as was cornering, and the suspension surpassed the original' Enfields in being slightly stiff on small bumps but swallowing up big ones like railroad tracks. About the only complaints I can think of. as I really like the bike, are a too-stiff throttle return spring, miniscule grips, and a front brake too tiny and inefficient to ever stop before nailing your ever present sacred cow. Furthermore one of Aub's men commented on the footrest rubbers being typically British, out of recycled inner tubes, as they already showed signs of scuffing after about 500 km.

In case we had forgotten the Enfield was made in India, you might remember the old story about the Scottish welder who was walled up in the double plating on the Great Eastern and could be heard hammering on stormy nights. Our bike had its own ghost that, when the engine was kicked over but failed to fire, would whine “im-shi! " which apparently means ***-off in heathen. Be that as it may, we mightily enjoyed this coelacanth from an age when motorcycles were to be played with, fiddled with, and adjusted through their little trapdoors instead of taking them to the neighborhood friendly (and expensive) Wombat dealer. Long stroke is not dead, good shifting is not dead, a refined exhaust note is not dead; long live a 350 overhead that feels like a fussless 500 flathead! And join us as we putt oft' into the distance on our Instant Classic singing the old Indian folk song:

The man who's worthwhile Is the man who can smile When they put too much starch in his dhoti.

ENFIELD

$1350

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSelling the Sizzle

November 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

November 1977 By Len Vucci -

Features

FeaturesToo Much Government Is In Our Future

November 1977 By Lane Campbell -

Features

FeaturesItalian Spoken Here

November 1977 By Jean Crabb -

Roundup

RoundupThe Victory Continues

November 1977