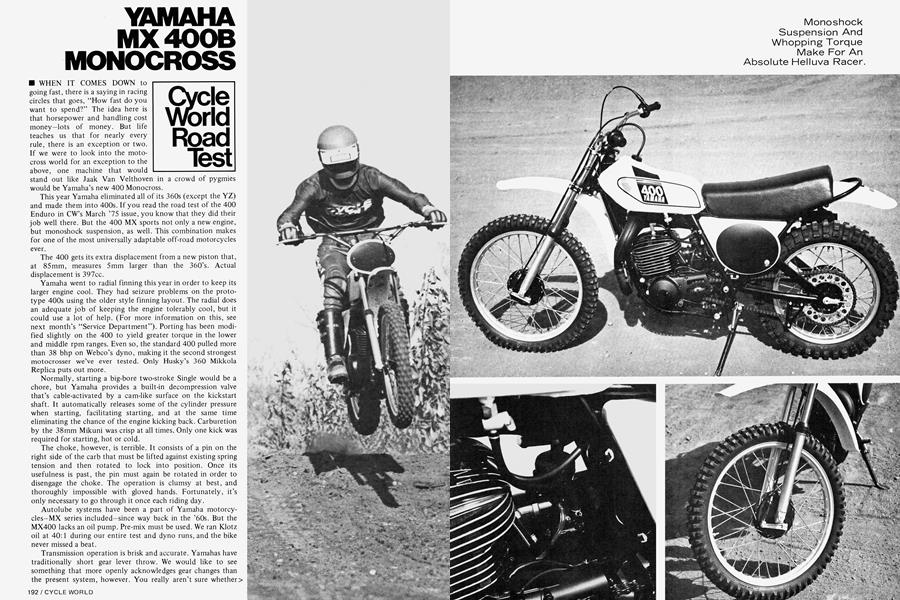

YAMAHA MX400B MONOCROSS

Cycle World Road Test

■ WHEN IT COMES DOWN to going fast, there is a saying in racing circles that goes, “How fast do you want to spend?” The idea here is that horsepower and handling cost money—lots of money. But life teaches us that for nearly every rule, there is an exception or two. If we were to look into the motocross world for an exception to the above, one machine that would stand out like Jaak Van Velthoven in a crowd of pygmies would be Yamaha’s new 400 Monocross.

This year Yamaha eliminated all of its 360s (except the YZ) and made them into 400s. If you read the road test of the 400 Enduro in CW’s March ’75 issue, you know that they did their job well there. But the 400 MX sports not only a new engine, but monoshock suspension, as well. This combination makes for one of the most universally adaptable off-road motorcycles ever.

The 400 gets its extra displacement from a new piston that, at 85mm, measures 5mm larger than the 360’s. Actual displacement is 397cc.

Yamaha went to radial finning this year in order to keep its larger engine cool. They had seizure problems on the prototype 400s using the older style finning layout. The radial does an adequate job of keeping the engine tolerably cool, but it could use a lot of help. (For more information on this, see next month’s “Service Department”). Porting has been modified slightly on the 400 to yield greater torque in the lower and middle rpm ranges. Even so, the standard 400 pulled more than 38 bhp on Webco’s dyno, making it the second strongest motocrosser we’ve ever tested. Only Husky’s 360 Mikkola Replica puts out more.

Normally, starting a big-bore two-stroke Single would be a chore, but Yamaha provides a built-in decompression valve that’s cable-activated by a cam-like surface on the kickstart shaft. It automatically releases some of the cylinder pressure when starting, facilitating starting, and at the same time eliminating the chance of the engine kicking back. Carburetion by the 38mm Mikuni was crisp at all times. Only one kick was required for starting, hot or cold.

The choke, however, is terrible. It consists of a pin on the right side of the carb that must be lifted against existing spring tension and then rotated to lock into position. Once its usefulness is past, the pin must again be rotated in order to disengage the choke. The operation is clumsy at best, and thoroughly impossible with gloved hands. Fortunately, it’s only necessary to go through it once each riding day.

Autolube systems have been a part of Yamaha motorcycles—MX series included—since way back in the ’60s. But the MX400 lacks an oil pump. Pre-mix must be used. We ran Klotz oil at 40:1 during our entire test and dyno runs, and the bike never missed a beat.

Transmission operation is brisk and accurate. Yamahas have traditionally short gear lever throw. We would like to see something that more openly acknowledges gear changes than the present system, however. You really aren’t sure whether you’ve made a complete shift until you gas it. Then, if you missed the shift, it’s too late. The spread of ratios through the gears is close, but with the tremendous range of power that the engine produces, a much wider set of ratios could be employed without any problem.

Wheels differ little from last year. The hubs are identical, but different material is used for the rear brake linings and this eliminates the grabby effect of previous binders. The front brake is an industry standard, light and progressively powerful. D.I.D. rims are standard and, like the Dunlop Sports tires (3.00-21 and 4.60-18), are a carry-over from the YZ series.

Paint styling is new this year, Yamaha, like some of the consumers, having tired of the yellow and black stripe scheme that dominated its racing machinery last year. Although on this particular Yamaha the colors are yellow and black, they are so attractively designed and blended by Molly onto a white background that you really don’t notice the similarity between these colors and previous ones. Fenders are white, also, as are the side panels that are covered with “stickum” paper for number plates. After a couple of trips to the quarter car wash, the paper peels right off. Shelf paper makes a nice replacement.

The telescopic front forks really surprised us. Action was better than we’ve ever experienced from Yamaha forks. Spring rates are perfect and the damping is well controlled. We received the bike with the fork tubes poking up about an inch and a half above the upper steering crown. Figuring that Yamaha had set the steering up that way on purpose, we left the forks in that position during the initial weeks of testing. The machine steered extremely well and could be stuffed into soft, sandy corners without any of the “folding under” tendencies we’ve encountered on older Yamahas.

Then when contemplating riding out in the desert, we decided to drop the fork legs down all the way to increase the rake and improve high-speed stability at the expense of some line-holding capability in corners. But Yamaha had machined down the diameter of the tubes between the steering crowns. While we had well over an inch sticking out above the upper crown, there was only about a half-inch of the “fatter” part of the fork leg above the lower crown. Therefore, we could only drop the legs half an inch. This did not help enough to eliminate a slight tendency of the front end to “search” at high speed. Dropping the legs lower would have reduced the amount of area that the lower clamps would have been able to pinch. We already had discovered a little bit of side-to-side flex in the forks. It wasn’t bad, but dropping the legs would have increased the leverage of the wheel at the axle, as well as diminishing the strength of the pinch bolts at the lower crown. The machine would have been extremely difficult to control at high speeds.

Some desert riders, already successful on their 400 Monocrossers, have told us that installing a 3.50-21 front tire keeps the front end on top of the sand and also serves to increase the rake to the point where front-end search is non-existent.

Performance of the rear suspension is tops. We’ve ridden all sorts of forward-mounted arrangements, and, while many of them are superb, the Yamaha monoshock system shines just a little bit brighter. First, “damping fade” is a phrase that doesn’t exist in the vocabulary of the monoshock owner. Second, damping on our test unit was perfect, as was the spring rate. Extra springs are available from Yamaha dealers, although not every dealer is yet capable of servicing the shock unit or altering the gas pressure to suit desired damping characteristics.

DYNAMOMETER TEST HORSEPOWER AND TORQUE

The double cradle frame on the 400 is extremely rigid. It should be. The bike is no lightweight at 245 lb. ready to race. In reality, the frame seems to be built for ruggedness rather than lightness, even though the suspension absorbs just about everything you come across and therefore does not tax the frame as heavily as a conventionally sprung system.

Performance on any track is incredible. On well-prepared surfaces, the Yamaha flies. We had a chance to race the Yamaha against the Husky 360 we tested last month. As long as the track was in good shape, the Husky could be kept ahead of the Yamaha. It has a little bit more top-end power, has slightly better front forks, and is a whole bunch lighter. But put it on a dry track and the Yamaha will stomp just about anything.

The dyno gives us part of the reason. The Yamaha has a fatter power curve than the Husky. It pulls stronger at lower rpm, stronger through the middle, and then loses out at the very end. Its off-the-pipe to on-the-pipe transition is quite smooth, too. And the Yamaha carries more flywheel, which helps deliver the power to the ground even when the ground seems unwilling to accept it. The soft tire compound found on the 4.60 Dunlop also aids traction, although the tire wears quite fast.

Very little body motion is necessary in order to make the Yamaha do what you want it to. It isn’t necessary to slide forward for the corners unless the track is dry. Then, only a little. Better yet would be to buy a Metzeler for the front end. Then you wouldn’t have to move at all!

No matter how good your suspension, you occasionally may find yourself over your head, with the bike starting to take over control of the situation. On the Yamaha, just gassing it brings everything back into shape. In power-on situations control returns to the rider.

Because of the great action of the rear suspension, the 400 is finding and will continue to find great favor among desert riders. The shock absorbs whoop-de-doos without a hint of dissention, and speeds can be attained that may never have been possible before. For running on the really wide-open spaces, we suggest that you purchase a larger countershaft sprocket. One more tooth (15) would do nicely, although the engine is capable of pulling even taller gearing. Top speeds in excess of 90 mph are certainly possible, though with that type of gearing first would require a lot of clutching to get going.

The seat is comfortable enough for long desert races. The handlebars are well-shaped and provide good control. The footpegs are cleated, spring-loaded items. But the Yamaha lacks a large enough tank. At just over two gallons, the depository doesn’t hold enough to feed the thirsty reed-valve engine for very long. Most normal accessory tanks will have a tough time fitting, since the Yamaha tank is short and the frame tubes beneath it are wide because of the presence of the monoshock. Also, the up-pipe comes very close to the existing tank. Additional volume will have to be found upward.

This has got to be the age of revolutionary design. Most manufacturers have done their homework, and, because of that, many new bikes that are revolutionary fail to distinguish themselves from the pack. Yamaha’s 400 Monocross, however, will not suffer that fate. It’s a bright spot in a sea of gray. g>

YAMAHA MX 400B

$1486

View Full Issue

View Full Issue