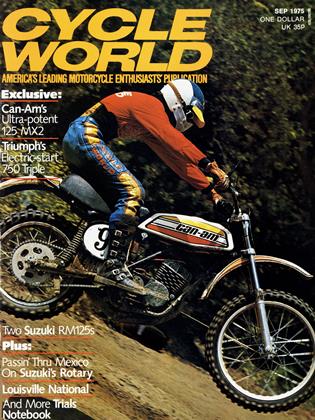

CAN-AM 125 MX2

Cycle World Road Test

THE HORSEPOWER BATTLE is an intricate game of one-upmanship that was once played strictly from the advertising table. One manufacturer after another tried to have the most powerful motocrosser—with the widest powerband—all without so much as a porting change over the previous model. But that has now developed into an honest, highly-accurate portfolio of facts and figures taken (mostly) from the almighty Webco dyno.

When the truth began coming out, the ones who had to really hide their heads were those who had devised 125 MX horsepower ratings. Not only were the so-called 25hp screamers falling short of their projected output, but few, if any, could struggle past the 15hp mark. Then as the more serious MX efforts started zipping out of Japan (namely the Elsinores, TMs, KXs and YZs), the actual horsepower figures became a little stronger. Sixteen and sometimes 17 horses were not uncommon. But the consumers wanted even more. So, manufacturers pulled out as many stops as prudence and profit margins would allow, sending out such machines as the Yamaha YZC and the new Suzuki RM 125 to hover right around the 20hp mark.

Meanwhile, the 250 class was having the rug pulled out from under its 24-29hp by Can-Am and its incredible 34hp-plus rotary-valve monsters. Eyes bugged out and 125class racers salivated madly when they thought what might happen to the small-bore Can-Am should the factory decide to unleash a similarly progressive weapon in eighth-liter form. With the introduction of the new Can-Am 125 MX2, many riders will feel that their prayers have been answered. And, in some cases, they will have. As a quick glance at the dyno chart reveals, Can-Am’s smallest motocrosser follows the family tradition of being the most powerful racer in its class. Facts and figures aside for the moment, let’s look at how Can-Am arrived at such a powerful motor.

First of all, intake timing has been extended. The MX2 rotary-valve opens the port 5 degrees earlier and keeps it open 10 degrees later than the MX1 valve. This allows much more of the fuel/air mixture from the 32mm Bing to enter the engine.

For transfer of the mixture from the crankcase to the combustion chamber, four transfer ports do the job that was previously handled by only two. The ports, individually, are smaller than the MX1 transfers, but their cumulative flow potential is greater. Once the gases have been spent, they are flushed through an exhaust port that is 1.2mm taller and 4mm wider than before. This new porting package provides the Can-Am with its incredible power. And the inner-rotor Motoplat pointless ignition (replacing the electronic Bosch flywheel ignition), offers less inertia restriction and produces a quicker-revving engine.

01 course, when a bike delivers as much horsepower as the Can-Am does, the powerband suffers. The MX2 pulls strongly through a much narrower range than did its predecessor. The Bing carburetor works exceptionally well as long as the engine is on the pipe. Off the powerband the engine feels as though it wants to pull more strongly than the carb allows it to. We’ve experimented with jetting and needle positions, but so far to no avail. It’s not that the carburetion needs much fiddling; it’s only off by the slightest bit. We feel that with the proper carburetion the powerband could pick up as much as 1000 usable rpm. We’ll continue to experiment with it and report back in the future.

As with the Elsinore, power comes on strongly at 6000 rpm and pulls like the devil until 9000, at which point the door slams abruptly on the revs. At first the sensation of running out of rpm so quickly on a 125 bothered us, particularly when, sitting next to the Can-Am in the CYCLE WORLD shop, were such ear-piercing rev-’em-up wailers as the RM 125 Suzuki and the 125 YZC monoshocker. But when we became accustomed to the fact that we were riding what feels like a high-powered Elsinore, our shift foot began dancing on the lever of the six speed transmission, keeping the little jewel running where it was happiest.

Once You Get It Into Third Gear, It'll Eat Anything Short Of A Full-Blown 250.

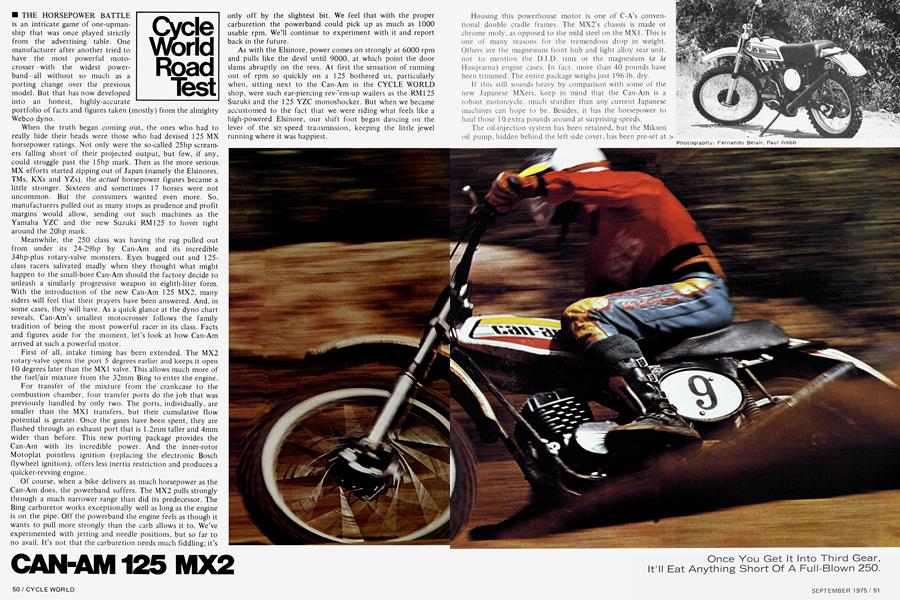

Housing this powerhouse motor is one of C-A’s conventional double cradle frames. The MX2’s chassis is made of chrome moly, as opposed to the mild steel on the MX1. This is one of many reasons for the tremendous drop in weight. Others are the magnesium front hub and light alloy rear unit, not to mention the D.l.D. rims or the magnesium (a la Husqvarna) engine cases. In fact, more than 40 pounds have been trimmed. The entire package weighs just 196 lb. dry.

If this still sounds heavy by comparison with some of the new Japanese MXers, keep in mind that the Can-Am is a robust motorcycle, much sturdier than any current Japanese machines can hope to be. Besides, it has the horsepower to haul those 10 extra pounds around at surprising speeds.

The oil-injection system has been retained, but the Mikuni oil pump, hidden behind the left side cover, has been pre-set at a constant volume: that is, wide open. Not only does this eliminate the hassles of pre-mixing, but it is a much more efficient way to lubricate such vital areas as the lower-end bearings. Thanks to the Can-Am’s oiling system, these bearings are force-fed a constant supply of lubricant. Engine life should be exceptional.

The oil tank on the MX2 is actually its backbone frame member. The top tube running under the fuel tank from the steering head is a massive sealed compartment. It can be filled from a spout behind the steering head. Capacity is in excess of two quarts. During our entire test, the Can-Am frame never exhibited any behavior that would not have made its designers proud. The tremendously rigid structure is a perfect example of what a great chassis is all about.

Complementing the frame in the handling department are Spanish Betor forks and gas/oil Girling shock absorbers. The. action of the forks was, as expected, flawless. But the 6.5 in. of travel falls about an inch short of what most really competitive MXers sport nowadays. Fortunately, extending the travel is a simple operation, one that we detailed in last month’s 175 “Can-Am Facelift” article.

The forward-mounted dampers at the rear can’t be faulted. We learned that earlier in the year when we tested the 360 Mikkola Replica Husqvarna. The ride delivered was extremely precise. If anything, the degree of “feel” transmitted to the rider made the Girlings seem slightly harsh, yet you always knew exactly what was happening at the back end. The only surprise lurking in the rear suspension was an occasional tendency to deliver a burst of traction in situations where experience told us it couldn’t happen.

But the Can-Am, despite its admirably executed design, is not perfect. One of two things that we didn’t like about it was the brakes. At first we thought that they needed seating in. But as time wore on, we realized that they just weren’t going to get better. Several disassemblies to inspect the linings for high spots did eventually improve them to the point that, with enough pressure, they would haul the machine to a stop with competitive force. But you could still be out-braked if you weren’t watching it.

The second problem is even more serious than the brakes. You might by now be wondering why, with the type of power the Can-Am has on tap, the rock-steady chassis, excellent suspension, and such other neat goodies as Yokohama Super Digger tires, Magura levers, spring-loaded footpegs, and so on, we haven’t proclaimed the MX2 King of the 125 Class. Much as we’d like to, and even suspected we might have to, the Can-Am transmission design prevents us from doing so. Operation eventually loosened up to a Honda-type snicketysnick, but the factory really goofed in the selection of ratios.

First gear is right-on, but second is much too close to first and too far from third. After zapping quickly through the first two gears, you notice that you really aren’t accelerating very hard at all, yet the engine is screaming its guts out. Then, when you hit third, things really start to happen. In fact, once the Can-Am is in third gear or higher, there isn’t a 125 anywhere that will stay with it. . .not Yamaha Monoshocks, hopped-up Elsinores, RM Suzukis, or anything else you can name. And the distance that the Canadian machine puts between itself and the competition is even greater if a steep uphill comes into play. The torque that the Can-Am has just gobbles up the competition.

Although the choice of transmission ratios is subject to power characteristics of the engine, along with the primary reduction ratio and selected tire size, these ratios should be a consistently decreasing set of numbers. This is true because, as the engine gets into the higher gears, drag from friction, gravity, wind resistance, etc., becomes greater. Therefore, the motor cannot accelerate the machine at as fast a pace (ft./sec.) as it did in the previous gear, although faster than it will in the next one.

For the purpose of comparison, we took the overall ratios from a Honda 125 Elsinore and figured the percentage of gear ratio change, starting with the jump from first to second, and ending with the nearly indiscernible change from fifth to sixth. The percentages got progressively smaller just as expected. Then we did the same with our Can-Am test bike. The numbers that the Can-Am’s transmission provided us with all got progressively smaller, with the exception of the secondto-third change. This showed us on paper what we sensed out on the race track. Were second gear farther from first, the first-second percentage would be larger (which we feel the engine could certainly pull), and the second-third percentage smaller (which would get you into third gear farther up the powerband. and increase the acceleration rate).

But the incorrect second gear ratio holds the bike back. Accelerating out of hairpin corners or even off the starting line, other 125s put distance on the Can-Am until it gets into third gear. Did we say put distance? Hell, they eat it alive. The temptation is to get the Can-Am into third sooner than it is ready and then fan the clutch to induce wheelspin and let the engine rpm rise to a more efficient level. Sometimes you can get away with it, losing, at worst, only a bike length. But when it doesn’t work, the job of making up lost distance becomes even greater.

Thinking that one of the ratios out of a 125 or 175 T’NT Enduro gearbox might have more suitable reduction and thus save the day, we searched our tech manuals. No such luck.

As a complete unit, the Can-Am 125 MX2 is a competitive motorcycle. With aggressive riding on the right type of track (one with as few firstand second-gear turns as possible), you can slaughter the rest of the field. The rougher the track, the better for the Can-Am’s tine handling. High-speed cornering is also a breeze thanks to the spot-on steering geometry. The adjustable steering head allows the rider to alter the geometry to his taste. Our test bike came set from the factory at 30 degrees. We wouldn’t change it.

With prices climbing ever upward, people expect more and more from new machinery. The more competitive the field, the more they expect. We can’t think of anything more competitive than 125-class motocross, or anything more capable than Can-Am of stepping in and taking over the Honda stranglehold that Yamaha and Suzuki have recently begun to loosen up. Can-Am has the power, it has the handling, the brakes can be fixed, and it has the reputation for being more than a one-season disposable motocrosser. Now, if it just had the right second gear ratio, it could take the 125 class home in its hip pocket.

CAN-AM

125 MX2

$1295

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOn the Snell Memorial Foundation Helmet Test

September 1975 -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

September 1975 -

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1975 By Joe Parkhurst -

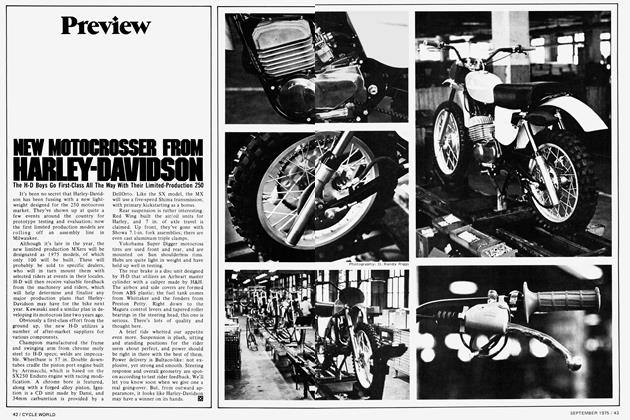

Preview

PreviewNew Motocrosser From Harley-Davidson

September 1975 -

Competition

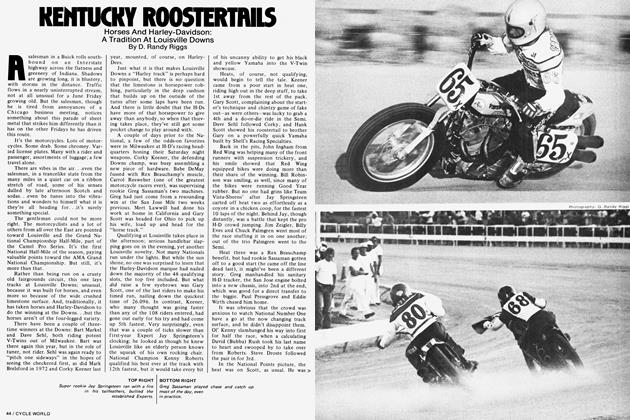

CompetitionKentucky Roostertails

September 1975 By D. Randy Riggs