BULTACO 360 ASTRO

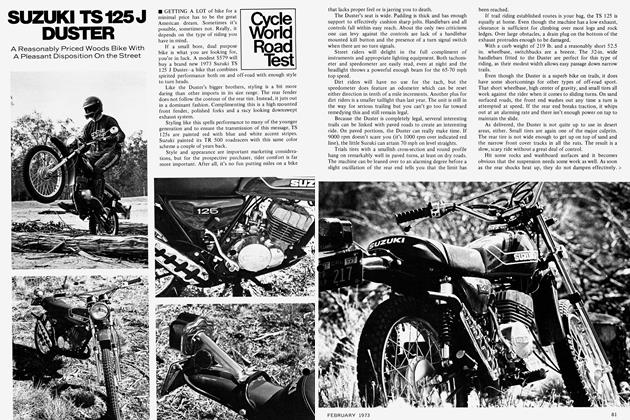

Cycle World Road Test

A Winner In The Midwest

RACING DOWN THE front straightaway with a full head of steam, your mind and full attention focus at one point, the predetermined spot just before the corner—and sometimes into it—where the throttle must be rolled back, the compression release pulled and perhaps the brake tapped for an instant. While all of this is going on, you unconsciously slide all of your weight forward and to the inside, wedging your right knee full force against the tank. Your steel-shod left boot contacts the turf and acts as a ski, an outrigger, groping for balance.

Power is applied to maintain the arc of the corner. As soon as the corner opens up, the throttle is twisted to the stop, rider weight is transferred to the rear wheel and your foot is lifted to the peg; a little body English and you disappear down behind the number plate as you and machine, now one,jet full speed down the straight. Once again all concentration is focused on the upcoming lefthand corner.

There are a whole kaleidoscope of additional thoughts that spin through the head of a racer as the corners approach in the blink of an eye, but these impressions should give you some idea of the thoughts flashing through our minds as we track tested Bultaco's new 360 Astro.

If the name Astro doesn't ring a bell, don't feel badly. Most people aren't aware that Bultaco is one of two companies to offer an out-of-the-box short tracker/half-miler for sale. Okay, but why? In Southern California it isn’t seen, but in the East and South this type of racing is a several-nights-a-week proposition. Every burg has its own horse or stock car track on which motorcycles are raced; and they draw the townfolk, bikes and riders by the truckload.

The Astro is the culmination of a lot of effort and experimentation on the part of a few good lightweight racers and a tremendous amount of feedback to Bultaco International from its dealer network. This very point should make it clear that the Astro is not a designer’s bike, but one created by and for racers.

Not only do you get a race-ready motorcycle for the nominal price of $1800 (this is certainly inexpensive by racing standards), but two sets of tires, a rear disc brake and dual ignition, as well. Think about it; this is at least $1000 less than the price of building one.

“At such a bargain price,” you say, “the Astro must be put together with water pipe tubing and glue. The engine is outdated and the thing handles like a hinge.” Well, nothing could be farther from the truth.

The engine and all of the running gear are held in place by the frame, so this seems like the logical place to start. There are certain similarities in design between this and the Pursang frame. The same high-grade chrome moly tubing is used, but, due to the two radically different purposes for which these bikes are intended, there is not one iota of similarity in frame geometry. Because the Astro has to turn and respond quickly, and must do so on a relatively smooth course, it sports a steeper fork angle and less trail than the MX bikes.

The 19-in. swinging arm is the same length as the MXer’s. The difference occurs in the mounting position of the shocks. The Astro’s shocks are mounted in the standard (now archaic) position. To properly lubricate the swinging arm bushing, there is a grease fitting installed at each pivot point, something not seen on the Pursang. Axle adjustment is unique compared to that on other production bikes. Wheelbase can be varied by three inches, or from 53 to 56. The plates on either side of the arm can be moved to four different positions; the toothed cam makes fine chain adjustment from there. This change in wheelbase does two things at once, things that may be necessary to “tune” the bike from one track to another.

It should go without saying that lengthening or shortening the wheelbase slows or quickens the response of any bike. At the same time, weight distribution is also affected. Shoving the wheel all the way forward puts less weight on the front wheel and more on the rear. Pulling it to the rear has the opposite effect. More weight up front is usually associated with short courses that require faster handling, but there is a happy medium between front-end steering and rear-wheel traction. Rider preference is also a big factor. With this much latitude in adjustment, most styles can be accommodated.

Next comes the suspension. Components on the Astro are manufactured by another Spanish company: Betor. From the outside, the forks appear to be the same units fitted to the Pursang, but close inspection reveals that this isn’t so. Travel of these is considerably shorter. We measured a stroke of nearly 4.75 in. Internally the dampers are different; there is more rebound damping. Generally speaking, the smoother the course, the stiffer the suspension.

The rear damper units are not much different from the front in that there is a minimum amount of travel, in this case approximately three inches. There are five different spring preload settings. And these dampers can be rebuilt by the> average individual, as they require no special tools to disassemble. Seals are available.

There are several companies that make spool hubs, a must on a track racer. Weight and strength are a consideration here and the spool fulfills both of these requirements. But with the Astro it isn’t necessary to hunt these parts down; the bike comes equipped with spool hubs made from Dural. Aluminum spacers on either side of the hub act as adaptors for the disc brake and sprocket. These adaptors are attached to the hub by Allen-head bolts, which also serve to align the brake and sprocket. To secure these, the end of the adaptor is threaded and a special nut holds it all together. By removing the wheel and spinning the nut off (with a special wrench), the sprocket and disc can be changed from one side to the other. This allows a rider or tuner to quickly reverse the wheel if a fresh tire edge is needed. Remember, this thing only turns left.

The front hub is made from the same material as the rear. There are no flanges to attach adaptors; none are needed. By simply removing the axle, the front wheel, too, can be reversed.

Shoulderless Akront rims are used fore and aft. Surprisingly enough, there is no visible means—such as rim locks or screws—to prevent the rear tire from turning on the rim. There are, however, serrations on the inside of the rim that hold the rubber in place. We used 18 psi in the rear tire and did a lot of wheelspinning. The tire didn’t move a fraction of an inch.

Pirelli skins come mounted on the wheels. D/T Goodyears or Carlisles, whichever are available at the time, make up the second set the Astro comes with. Each of these tires can be used on a goodly number of tracks, but chances are that a well-equipped racer will have many different varieties. Tires are matched not only to track surface, but to rider style, as well.

We expected to find the Astro outfitted with 4.00-19 tires, which was the case in the rear. But, oddly enough, a 3.50-19 is fitted to the front. According to Bultaco, feedback indicates that a larger tire up front makes the front end mushy. This may be the case on a short course, but we would have preferred the larger tire for the half-mile.

To obtain the proper feel for the disc, two different manufacturers are used for the various brake parts. The single-acting, floating caliper unit and master cylinder are products of Kelsey-Hayes. The disc itself comes from Kennedy. It looks to us as though the master-cylinder bracket could stand some beefing up. The cylinder is mounted to a single piece of strap metal between the V in the frame. There is a lot of flex at this bracket, making it a good candidate for fatigue. Although we haven’t heard of any particular problems, it might be a good idea to keep an eye on things in this area.

The arm that pushes the piston pivots on a split-pin on the master cylinder. There are three holes in the arm to adjust leverage and travel of the brake pedal. The last hole down on the lever gives the most travel and leverage; this is where we ran it.

The nylon-braided, plastic-covered brake line showed signs of wearing against the rear fender. Nylon tie straps can be used to prevent this, but we suggest the line be replaced with the heavier-duty steel-braided variety.

The 10-in. disc and floating caliper do a superb job of getting the Astro stopped in short order. Brakes are something relatively new to the track-racing scene, having made their debut in the mid ’60s. And while they aren’t used as often as spectators might think, when they are needed they may mean the difference between staying in command of the situation or becoming the situation. We can’t think of a single complaint in the area of brake operation.

Now we come to the heart of the Astro, the power plant. From the outside it looks like any 250/360 Bultaco. . .almost. The general layout is familiar: a single-cylinder two-stroke with the cylinder inclined slightly forward. The crankcases remain the same as on the other models. The head is designed to accept two spark plugs, one cold, the other slightly warmer. This dual ignition assures complete combustion.

Between the two plugs is another hole drilled and tapped to accept a compression release, a definite asset for track racing. More emphasis is placed on this one item than on the brakes.

It slows the bike just enough to set up for a corner or to change or maintain a line when into a corner. Because of a supply problem from Spain, it is up to the buyer to furnish a compression release.

Inside the cylinder, the ports are more radical than the Pursang’s; the intake is lower, the exhaust is higher and the transfer area is greater. Because of the on/off type of racing the Astro sees, a narrower power range is acceptable. For the serious racer who wants to tune his engine’s power from one track to another, there are 17 different flywheel weights available. The heavier weights provide the answer to slippery tracks where tractable power is needed, while lighter weights work right on the fast, wide open tracks.

Crankshaft reliability has been improved by use of a large, heavy-duty 22mm-diameter crank pin. This is much larger than the pins used in other Bultacos.

The Astro’s concentric, Spanish-built Amal carb has a> 36mm venturi. Air is filtered through a washable Twin Air foam filter. Although the filter is exposed to the elements, chances are good that this bike won’t be run in conditions that are worse than dusty. But a rubber flap on the bottom edge of the rear fender would help keep the engine cleaner.

Power is transferred from the crank to the gearbox via a duplex chain and wet clutch. There is no chain tensioner to compensate for slack, but this doesn’t seem to be a problem as long as the chain is replaced from time to time. Once or twice a season should do it. The clutch and five transmission ratios are the same as the Pursang’s.

According to professional AMA racing rules, the Astro 360 is a legal machine for short track racing (an oval track less than 2250 ft. in circumference) in Novice, Junior or Expert divisions. On the longer dirt tracks (i.e. half-mile, mile), only Novice-classed riders may compete on a 360cc Single.

Starting in second gear on the half-mile was the best way to get off the line in a hurry. Halfway through the first corner we caught fifth and never shifted again. With proper gearing for short track, the same situation should exist.

Those two plug leads for the dual ignition come from a large Femsa coil under the tank. The sending unit is driven off the left side of the crank. There are no points to wear and change the correct ignition timing. Once this system is set, forget it.

There is no question in our minds that the Astro can win both short track and half-mile races. The only question is, where? In Southern California we are faced with the invasion of the screaming Yamaha 250 Twins. In addition to their edge on power, they work well at our only major track. . .Ascot. First place is up for grabs at most other tracks around the country. The Single can and does hold its own. And part of the Bultaco’s appeal is its low price, ease of maintenance and tuning simplicity. Chances are that if things do go wrong, it will cost half as much as a Twin to repair.

Today, in a world of diversification, Bultaco continues to build performance and competition-oriented bikes. The Astro is a good indication that they are going about this task in the right manner. |oJ

BULTACO

360 ASTRO

SPECIFICATIONS

$1795